On Monday, September 30, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed legislation banning private, non-profit institutions from considering legacy and donor connections in college admissions. Since this ruling, California has become the fifth state to prohibit the use of legacy and donor preferences in college admissions, following the states of Colorado, Illinois, Maryland, and Virginia, which have put into place similar measures with the goal of promoting equity and reducing favoritism in the higher education admissions process.

The ban, originally proposed by San Francisco Assemblymember Phil Ting, takes effect beginning in September 2025. In a press statement, Governor Newsom stated, “In California, everyone should be able to get ahead through merit, skill, and hard work. The California Dream shouldn’t be accessible to just a lucky few, which is why we’re opening the door to higher education wide enough for everyone, fairly.”

As a result of the Regents Policy 2102, since 1988, the institutions within the University of California system have not considered legacy or donor based admissions; however, many private colleges like Stanford University remained exceptions to this practice. This ban, specifically targeting private institutions, seeks to level the playing field for all institutions in California.

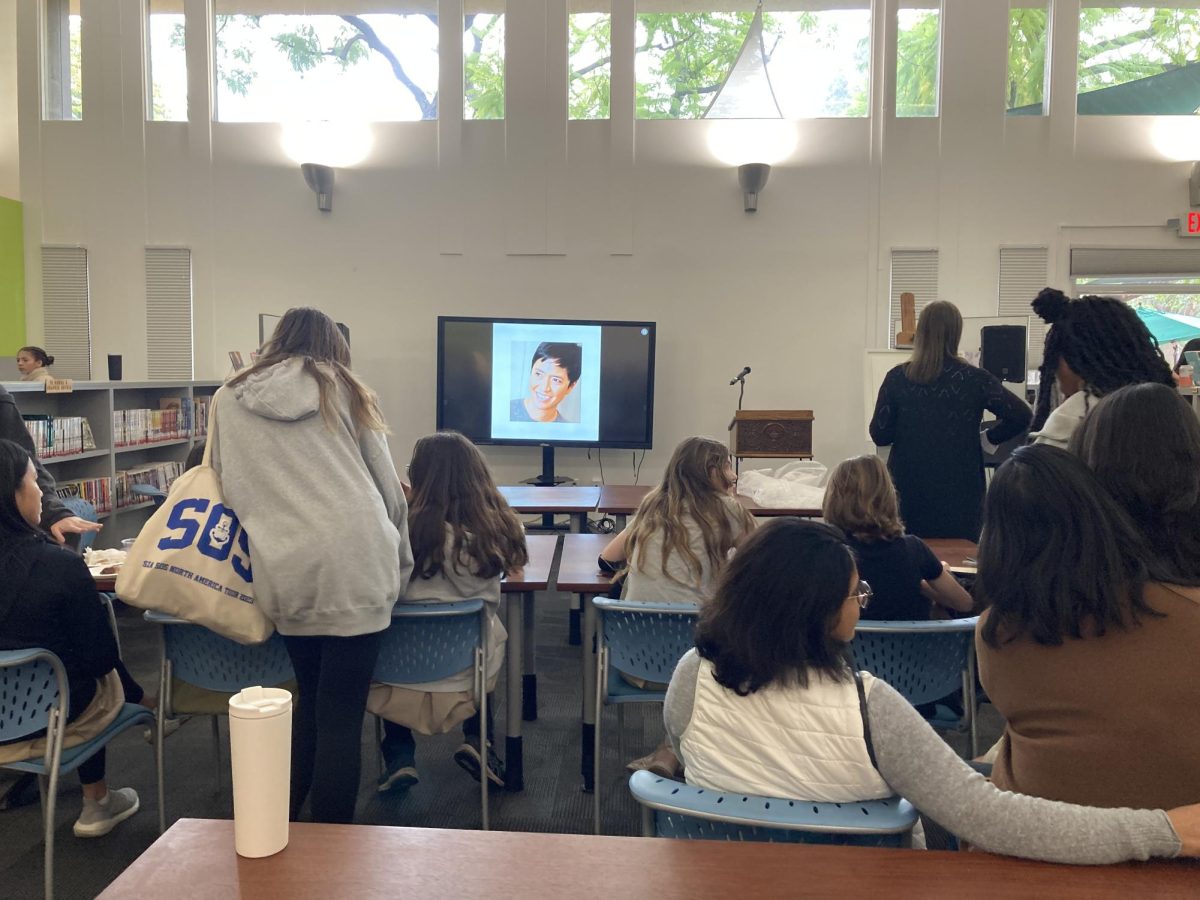

The Westridge College Counseling Department is familiar with navigating the application process while adhering to the Regents Policy, as well as California’s ban on affirmative action, which prohibits the consideration of race, ethnicity, and sex.

Dr. Monique Eguavoen, Director of College Counseling at Westridge, says adapting to this ban will be no different. “Our support and robust offerings will remain the same, but how we discuss data, results, influencers, hooks, and balance to the college list, can differ as a result of this,” she said. Dr. Eguavoen added that the ban impacts only a small portion of Westridge students. “Everyone cannot utilize legacy admission,” she said.

Despite this, she emphasized her department’s commitment to guiding students during the evolving admissions landscape, saying, “as we move forward, we’re just going to rely on our expertise and familiarity with similar landscapes at public institutions in California that do not consider familial connections in the admission process.”

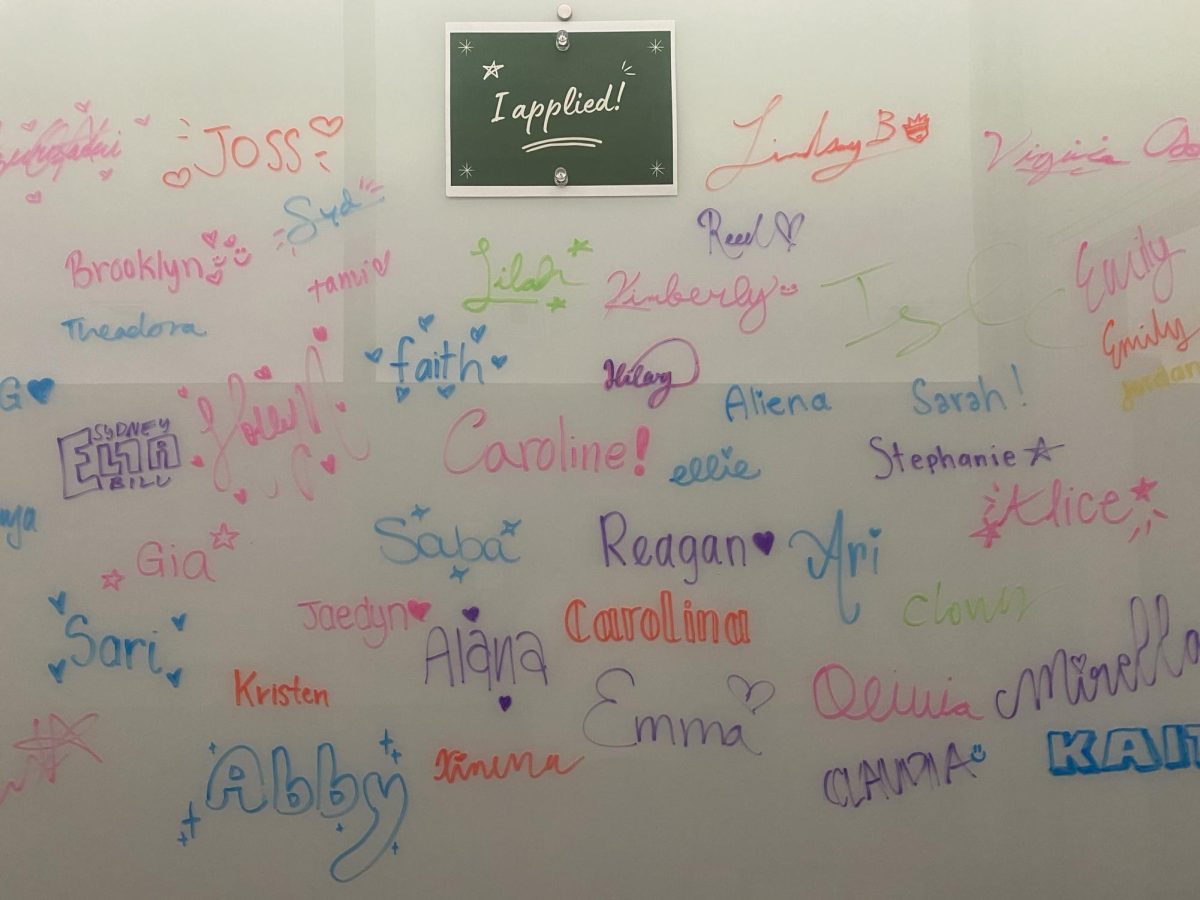

The ruling has also sparked conversations among Westridge students. Senior Ginny A. ’25 expressed strong support for the decision. “You can be the smartest person in the world and have an amazing work ethic, but not have as much money,” she said. “Like, wouldn’t they [universities] want that person over somebody that just donated a ton of money? I think the ruling is pretty great. It’s more fair for everybody.”

Ella S. ’25 was surprised to learn how significant legacy admissions have been in the past. “I didn’t actually think anybody was accepted to a school because of how much money their family had donated before. I thought it was a consideration because they happen to have that history of the school, but also academically, they’re qualified.”

For younger students like junior Michaela R. ’26, the ruling feels distant but positive. “It doesn’t affect my life as much, but I hope that helps some people out when they want to get in but can’t, because maybe spots are taken [by legacy] already,” she said.

In agreement, Zoe T. ’26 said, “It opens more space to people who don’t necessarily know people in high places. So, yeah, I agree with this ban.”

To conclude, Dr. Eguavoen expressed her plan for the forthcoming application cycle: “As our office learns more about the updates from colleges and universities, we are going to share that information, of course, with the different classes as well as administration.” She continued to say, “Our commitment remains focused on the student and their family, ensuring the student can authentically represent themselves in the application process.”