6:59 AM on Monday, November 6.

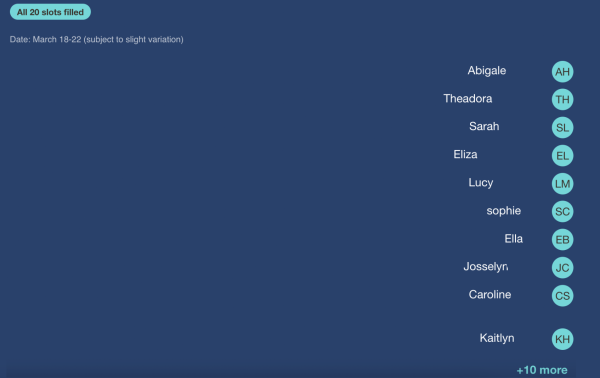

Sydney S. ’25, along with every other student in the junior class, sat patiently at her computer, waiting for 7:00, when the first-come, first-serve SignUpGenius form would go live and juniors would select their Discovery Week trips. Technical difficulties kept Sydney from successfully selecting and saving her first-choice trip, and by the time—just minutes later—she was able to scroll down to the option she’d hoped for, all the slots were filled.

Sydney was not alone. For juniors, this year’s Discovery Week sign-up was a logistical nightmare. Just about every junior had a horror story.

Junior Isla R. wasn’t alone in characterizing the sign-up process as “ridiculous.” She opened the form a minute before it opened and was still five minutes too late to select her top choice trip. After the website form continually crashed from the influx of students trying to get ahead of the game, an advertisement blocked Isla from accessing the site until she was left with only one option—one that her heart wasn’t into, and which she thought might even be unsafe.

Increased costs and destinations met with apathy at best raised the collective ire of the 11th grade, causing students to call into question the necessity and value of a celebrated—and mandated—Westridge tradition.

The school has long designated the week before spring break for experiential learning, both in our own city and overseas. Since reframing the program in 2022, freshmen and sophomores have stayed close to home to engage in local programming that introduces students to LA history, social issues, and civic life, ranging from cinema and STEM to ecology and immigration. The 9th- and 10th-grade Discovery Week offerings have stayed mostly consistent since Westridge returned to full-time in-person school.

In contrast, 11th- and 12th-grade options vary year to year. In 2024, 11th graders will travel across the nation to explore significant Civil Rights monuments in the American South, dive into the political and geographical landscape of the US/Mexico border, immerse themselves in culture, history, and urbanization in the Northeast, or admire New Mexico’s art—both natural and manmade. Seniors will fly off to Chile, Germany, Iceland, or Peru for experiential learning in global citizenry.

Underclassmen seem largely optimistic for the adventures ahead. 10th grader Josie T. is going on the “Cinema City” trip, which will take students to historic theaters, the Academy Museum, and movie screenings. She chose Cinema City because “it looked like a lot of fun. I did the STEM one last year and it was a good experience, but I wanted to try something new.” Josie is excited to spend Discovery Week with many of her friends, who will also be attending the same trip. And Ivory P. ’27’s love of all things outdoors—especially kayaking—encouraged her to sign up for “Ports and Pelicans: Economy Meets Ecology on the Coast.”

9th- and 10th-grade Discovery Week trips cost students $500. Although not insignificant for week-long excursions including food, transportation, and event tickets, no students seem too alarmed by the cost.

But bigger trips for upperclassmen come with bigger price tags. 11th-grade domestic trips cost $2,500, and 12th-grade international travel is $3,500—both $500 increases from last year’s cost.

Older students are questioning whether the payoff is worth the price tag.

“I’m a little peeved about the fact that Discovery Week is mandatory, but that they also make you pay for it,” said Sophie C. ’25. She also noted that cost is determined by grade level, not destination. “One of [the junior trips] is just taking a bus down to San Diego while others fly to multiple states. Yet we’re all paying the same amount.”

The trips are expensive—and costs keep going up. While financial aid is available for students with need, many feel that their family’s money could be going to better causes than a school trip about which they may not be thrilled—or even someone else’s travel.

Sydney, one of Sophie C.’s classmates, “did hear that the bulk of the money that my family would pay would go to the international trips and not entirely to my trip alone.”

According to Director of Upper School Mr. Gary Baldwin, Discovery Week money will not be redistributed across grade levels. Rather, funding is distributed by grade level. The school considers grade level trips as a block, allowing them to figure out the lowest cost they can charge for all trips. It’s possible that one 11th grade trip will cost more than another, but they’re all priced the same for students and families—which administration hopes will allow everyone to pick the trip they want without adding financials to the equation.

As for the price increase, Mr. Baldwin explained, “It’s not any secret that we are nationally in a period of reasonably high inflation, and stuff costs more this year than it cost last year. We work super hard to keep the costs down, but there’s a limit to what we can do.”

Cost is a contentious issue for students and families because Discovery Week isn’t an option—it’s a graduation requirement.

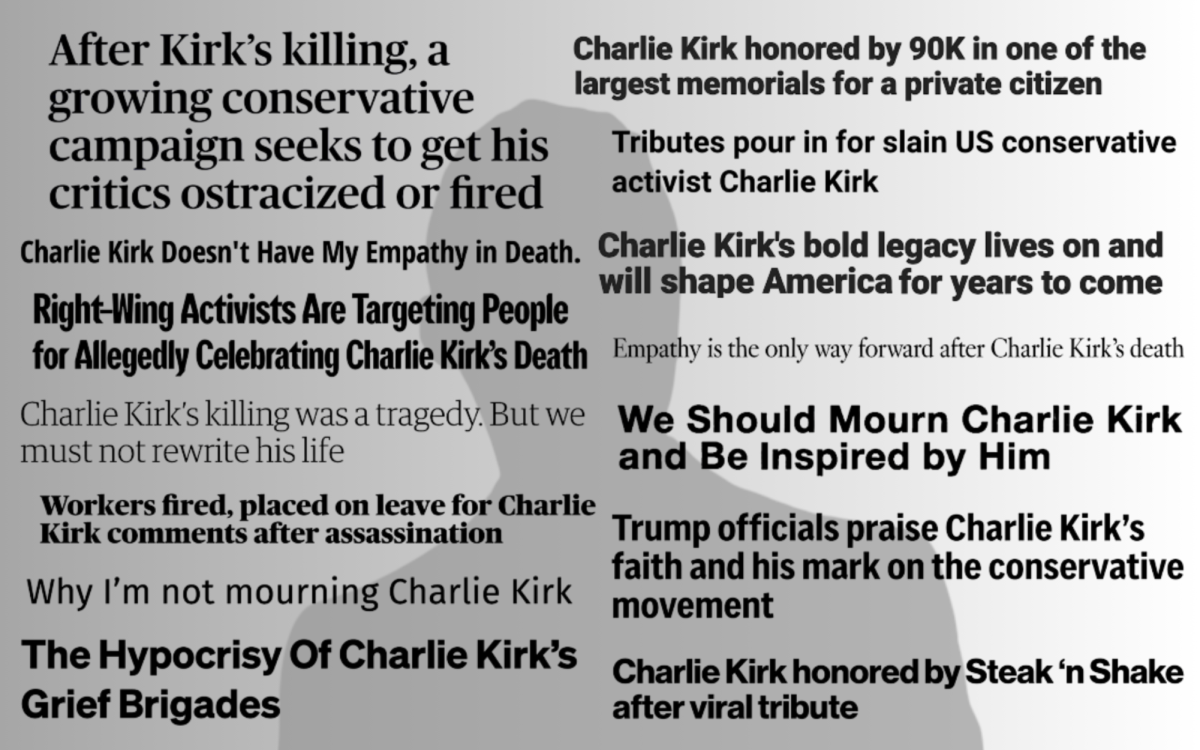

Administration insists that learning beyond the walls of a classroom—the core tenant of Discovery Week—is a necessary and valuable aspect of the high school experience; but some students would prefer an extended spring break to a week of learning-by-doing.

Sophie suggested that “juniors and seniors are especially stressed because we’d like those two weeks” —referring to both Discovery Week and spring break— “to visit colleges…and it significantly cuts into our spring break time and budget.”

Junior Alice C. thinks that “we already pay a lot of money to go to this school…having to pay thousands more dollars to graduate seems ridiculous and erroneous. I know the whole point of this new system for Discovery Week was to make it more equitable, but it’s not.”

Alice is referring to the pre-pandemic Discovery Week system (then called “Interim). Dr. Hilary Malspeis, Upper School Latin teacher, explained that local, national, and international trips—all priced by trip, individually, with at least one entirely free of cost—were open to every upper school student across grade levels. Seniors got first pick, but all students were able to choose their trip of choice. Some trips were grounded in relevant class material, including Latin-geared—but not exclusive—trips to Rome. Others had to do with teachers’ particular passions and talents, like Dr. Malspeis’s on-campus calligraphy classes.

One faculty member echoed students’ disillusionment with Discovery Week, attributing it to the new grade-by-grade trip selection and administration-driven, rather than student- and teacher-driven, itineraries. Before the pandemic, “Somebody did car repair, [somebody] did a cooking class…It used to be based on what students were interested in and what teachers were passionate about—that was what the organic, original Interim was about. Now, it’s lost its meaning. It’s lost its passion.”

But other teachers emphasized Discovery Week’s importance for both learning and fun. Mr. Grant Wood, Upper School math teacher, is taking 9th and 10th graders on a STEM-centered tour of Los Angeles. “Hopefully, the girls will realize that it is a great field to be in and that you can achieve success in it,” Mr. Wood said. And for science teacher Ms. Laura Hatchman, “Discovery Week, to me, should be about getting off campus, having fun, and being together.”

In spite of their scorn for sign-up mishaps and travel selections, juniors offered their hopes and dreams for next year’s international trips. Suggestions included Italy, “someplace in Europe…maybe an island,” Croatia, Brazil, and Korea.

![Dr. Zanita Kelly, Director of Lower and Middle School, pictured above, and the rest of Westridge Administration were instrumental to providing Westridge faculty and staff the support they needed after the Eaton fire. "[Teachers] are part of the community," said Dr. Kelly. "Just like our families and students."](https://westridgespyglass.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dr.-kellyyy-1-e1748143600809.png)