Accessing Academic Accommodations

Neurodiverse Students Find Support at Westridge

Students with learning differences can struggle without support in the classroom.

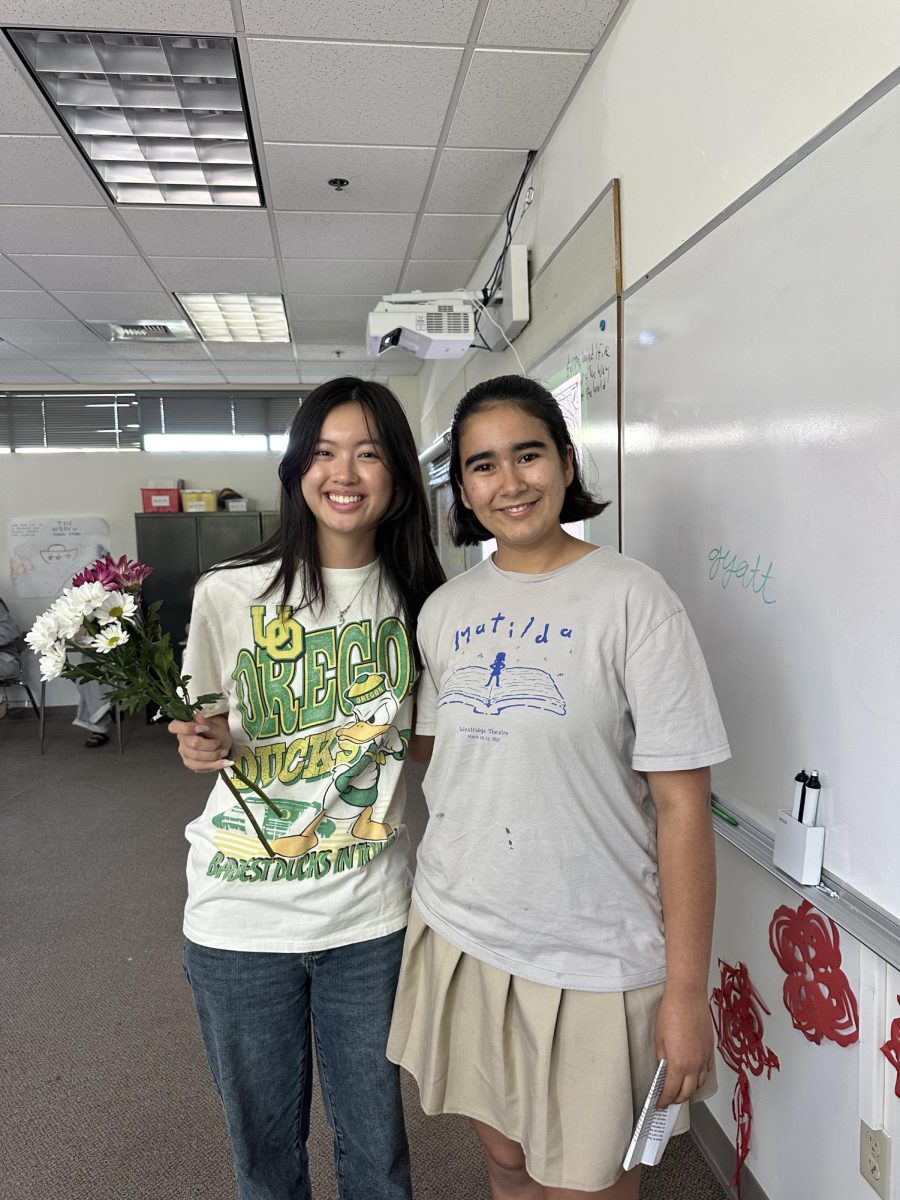

Bellamy S. ’24, who has academic accommodations, has no problem talking openly about her ADHD and anxiety. “It’s a reason for why I’m like this. And I feel like people should know that, you know, I’m not like this for no reason. It’s a thing with my brain.”

Bellamy’s experience of being a neurodiverse student isn’t uncommon. Westridge’s Upper School Learning Support Specialist, Ms. Tami Millard, estimates that about 10-15% of Westridge’s Upper School student population require accommodations due to either learning differences or medical issues. While Westridge students are often open about their neurodivergency, most conversations about academic accommodations happen behind closed doors. We investigated the process of acquiring, accessing, and implementing academic accommodations in the Upper School to shed light on the neurodivergent student experience and Westridge’s efforts to support its neurodiverse population.

Officially, Westridge offers four kinds of academic accommodations: extended time (usually around 15 percent), use of a computer, preferential seating in class—typically close to the board—and use of a calculator. Students are offered one, some, or all of these on a case-by-case basis.

There are also less formalized accommodations—recommendations, suggestions, and strategies teachers can incorporate into their instruction to aid particular students. According to Ms. Millard, these resources could include the use of audio books or working with a student to distill a major assignment into smaller, more manageable deadlines. Teachers are provided with learning profiles that detail each student’s required accommodations along with the aforementioned suggestions that allow teachers a bit more flexibility in the situation.

Learning profiles are meant to help teachers understand what will be most helpful for the student in each class, no matter the subject. Ms. Susie Murdock, Lower & Middle School Learning Support Specialist, explained that the profile is “really reflective of who they are as an individual.”

Dr. LaFave, Director of Counseling & Student Support, explained that after a student has been evaluated for learning differences by medical professionals outside of school, a report is sent to and reviewed by LaFave, Millard, and Murdock. The learning support team then determines whether accommodations are the right choice for the specific student. The information in the report is converted into a learning profile, which details a student’s needs as succinctly as possible. Ms. Millard writes learning reports for the upper school; Ms. Murdock writes for the middle school.

But the learning support specialists’ role often starts even earlier than the evaluation. Often, a student approaches one of the learning specialists explaining that they’re struggling with homework, time management, focusing in the classroom, or similar academic concerns. These kinds of complaints, which may suggest that a student is in need of support, prompt the learning specialists to investigate the issue further.

Dr. LaFave said, “It tends to kind of come to my attention when maybe there’s a student that’s struggling, and we’ve met with them and tried to figure out, like…what’s getting in the way of the learning, and then kind of observing them over a period of time and just having more questions than really answers. And so then we’ll ask the family to go and get an assessment so that we can better understand how this particular student’s brain works and how we can support their education here.”

For Bellamy, the process started with her own observations during sophomore year when she found herself struggling in class. She had trouble returning to tasks after taking breaks and needed to reschedule assignments. “I think the teachers could tell that something was up,” she said. “It started out with me being like, ‘I know this isn’t just study habits’ because it’s just not. It’s just not how that works.”

Bellamy and her parents—both with diagnosed ADHD themselves—pursued psychiatric evaluations and eventually academic accommodations, a process Bellamy described as long, arduous, and inconvenient. There were multiple rounds of tests and psychiatric screenings, official diagnoses from multiple doctors, prescribed drugs, and recommendations for formalized academic accommodations.

While her family worked with Ms. Millard, Director of Upper School Mr. Gary Baldwin, and school administration to get Bellamy’s accommodations, there was also a waiting period to evaluate the impacts of her newly prescribed ADHD and anxiety medications to see if additional accommodations would be necessary: ultimately, it was decided, they were.

At the encouragement of her mother, junior Charlotte (name changed to protect student’s identity) applied for academic accommodations after her ADHD diagnosis in 10th grade. She receives extra time on classwork, as well as time extensions and calculator use on standardized tests. Overall, Charlotte thinks, “It does help—to an extent. I think that accommodations are not an easy fix, but it does [sic] ease some of the pressure.”

Although teachers are generally helpful, there still seems to be a challenge in accessing accommodations.

Charlotte didn’t utilize her accommodations for a full year because they weren’t explicitly offered to her in class. “I don’t think your teachers are given notice that you have them, so you have to go up to them and ask for them to be in place.”

According to learning support team members and Westridge faculty, all learning profiles are, in fact, shared with teachers.

Charlotte is one of two students with academic accommodations in two of her classes, and she’s found it helpful when she has another person with whom to approach her teachers about accessing accommodations. She has found most teachers to be receptive after that initial interaction.

“But,” Charlotte said, “there are some [teachers] who’ve just failed to recognize the extent of what accommodations mean…”

She suggested that teachers have limited views of accommodations, which encompass in-class time extensions, but exclude extensions on work and projects outside of class. Charlotte also said that she feels the need to “prove” the need for her accommodations to her teachers, who sometimes dismiss or make light of them.

To Ms. Millard, self-advocacy is a natural part of the process. “So it’s really my job to meet with [students] to walk through that and help them understand, okay, if you’re now getting extended time, your teacher is not going to always have that in mind right away, because they’re not used to that. So you want to make sure this is how you communicate that to make sure, so it’s me kind of helping them learn how to be their own advocate and state their needs.” She noted that self-advocacy takes many, many years to master—and that a key part of her role is to support students with accommodations in getting what they need.

Lily N. ’26 said she has to constantly remind teachers of the support she needs. “All of them are supposed to know, and I can deal with it when they don’t, but it gets irritating.” Lily reflected that there have been times where teachers have already planned something and don’t offer an accommodating alternative for her.

Lily said, “There are moments where I don’t want to have a fuss about it… like ‘Is it really worth it to bring it up and cause a whole thing? Like, I should probably have an accommodation but I don’t really want to go through everything.’ ” Consequently, Lily doesn’t receive all the accommodations she needs.

Upper School Latin teacher Dr. Hilary Malspeis echoed Lily’s sentiment from an educator’s standpoint: “We know that students are uncomfortable at some times, and it is important that they learn how to self advocate. But…if there’s a specific accommodation that a student needs, like, [if] they need to sit in the front row, they might not say anything to their classmates, and sit in the back and just kind of, you know, ignore it, or make it seem as though they don’t have an accommodation.” In her mind, there’s more student-to-student than teacher-to-student stigma around accommodations.

In Bellamy’s classes, she’s had an overall positive experience with accommodations, and she knows how to navigate the occasional teacher slip-ups. “Well, I’ve heard some other stories from sophomores and whatnot that their teachers forget about their accommodations, and I’ve never really had that experience—the teachers always remember…I email them if necessary.”

However, academic accommodations are not the be-all, end-all fix for neurodivergent students in the classroom. Sabrina C. ’26 commented that, “Sure [accommodations] are a solution, but they don’t really solve the problem.”

Another junior, Emma (name changed to protect identity) said, “You can’t just take meds and fix all your problems, and you can’t just get extensions and fix all your problems. I think real accommodations would be, you know, actually putting the effort in to make sure that every individual student feels like they’re getting the education that’s right for them.”

Emma suggested that real support for neurodiverse students would mean a universal acceptance of the legitimacy of students’ accommodations—none of that need to prove accommodations like Charlotte described. She proposed better communication and more transparency between teachers and students on the whole. But Emma also addressed a broader issue: different students with different brains learn differently, and that Westridge’s program isn’t necessarily always indicative of that.

Like Sabrina and Emma, Bellamy believes that academic accommodations aren’t one-size-fits-all. She has accommodations for extra time, wearing headphones to focus, going to another room to complete work, and a recommendation for front-row seating. But, Bellamy said, “I’d say the core problem is the way things are explained to me…if they’re worded strangely, I just don’t process [them].”

Accommodations aren’t just doctors orders: they’re interpersonal issues, too.

In her biology and anatomy classes, Upper School science teacher Ms. Laura Hatchman takes an additional measure to support neurodiverse students by not timing any of her assessments. In doing so, all students can take the time they need, accommodations or otherwise. So, she usually doesn’t find it difficult to work with students’ needs. However, she did note that she understands the situation isn’t the same with other teachers who might structure their curriculum differently.

Ms. Millard described the learning specialists as the ones to fill in the gaps in teacher support. “Teachers honestly can only do so much. At some point, you’re going to have some students that are going to need much more advocacy and much more support beyond what a teacher can do for them. And the teachers also need education and support.”

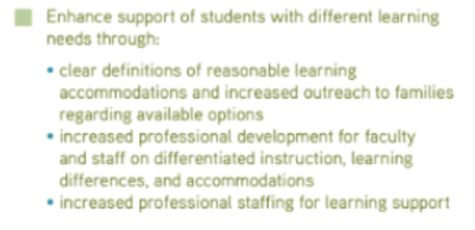

Westridge’s 2020-2025 strategic plan specifically discusses hiring more learning support staff, educating faculty, and increasing outreach regarding available options for accommodations. The school began its efforts with Murdock’s hiring in 2020, and now, the expanded learning support team is working towards helping teachers better understand how neurodiversity plays out in a classroom. Faculty are set to participate in training related to accommodations at the next professional development day in February. “So we’re having a lot of conversation and making some real specific plans toward how to make teachers feel more comfortable and equipped. And also to recognize that neurodiversity exists across the whole school community. It’s not just our students, but we have plenty of [neurodiverse adults] as well,” said Millard.

Ilena is passionate about stories— especially histories— good snacks, and bad puns. She has been on Spyglass for a very long time. Ilena is a senior.

Lauren Cho is a junior Spyglass Design artist. She has spent the last two years as a staff writer, but she wanted to join the Design Team this year to...

![Dr. Zanita Kelly, Director of Lower and Middle School, pictured above, and the rest of Westridge Administration were instrumental to providing Westridge faculty and staff the support they needed after the Eaton fire. "[Teachers] are part of the community," said Dr. Kelly. "Just like our families and students."](https://westridgespyglass.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dr.-kellyyy-1-e1748143600809.png)

Marty • Dec 13, 2022 at 9:15 am

Very thorough reporting on a complex subject. Nice job!