Although students who derive fiendish pleasure in taking standardized tests and are freakishly brilliant at it probably exist (at least in urban myth), I am not one of them; I have never been an easy-breezy test-taker. For me, doing battle with the SAT is a crazy-making exercise in intellectual stamina and psychological fortitude.

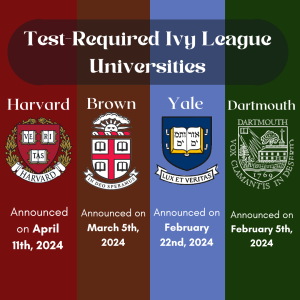

As I prepared for the March 9 SAT, I was feeling all of the usual apprehension associated with taking a test that may (or may not, in a test-optional admissions environment) materially impact my future when the stakes were suddenly raised even further: on February 5, Dartmouth College announced that it would reinstate its standardized testing requirement for the 2024-25 admissions year. Within a month, Yale and Brown had followed suit.

And just like that, the comfort I had felt in knowing that I wouldn’t have to submit my SAT scores if they didn’t align with the rest of my academic profile evaporated. Even though the majority of institutions’ test-optional admissions policies remain in place, what does the return of influential Ivy League schools to test-required admissions mean for applicants?

The SAT has been an infamous source of teenage angst and parental consternation as well as philosophical debate for decades. Critics have long argued that standardized testing erects barriers to college admissions accessibility and puts students who can’t afford tutors and test prep courses at a disadvantage. When the COVID-19 pandemic caused the vast majority of colleges and universities– including Ivy League and equally highly-selective “Ivy-Plus” schools like Caltech, Duke, and MIT– to adopt test-optional policies, many viewed it as an opportunity to increase diversity in admissions by encouraging underrepresented applicants who didn’t score as well as affluent peers to apply.

Now, Dartmouth, Brown, Yale, and, in the last couple of days, Harvard and Caltech– both of which had previously pledged to remain test-optional or test-blind, respectively, through at least one more admissions cycle– are reversing course, citing an influential study by Harvard-based Opportunity Insights, which found that SAT and ACT scores were better predictors of academic success in college than high school grades.

Further, admissions officers from these institutions no longer view standardized testing as a hindrance to admitting students from diverse backgrounds. According to a statement released on February 5, Dartmouth believes that “test scores better position Admissions to identify high-achieving less-advantaged applicants and high-achieving applicants who attend high schools for which Dartmouth has less information to interpret the transcripts.” Indeed, they feel that test-optional policies may hurt applicants from underserved communities by deterring them from submitting their scores, which, while lower than median admitted student scores, would have helped their applications by indicating an ability to outperform their environment.

Additionally, the qualitative elements of the admissions process may suffer from even larger racial and economic biases. Affluent students can afford to participate in expensive art and music lessons and club sports teams that bolster their applications. Those same students often attend private schools where teachers and counselors are expected to write glowing letters of recommendation. They also get essay advice and editing from expensive college counselors or highly-educated parents.

Acknowledging the inequities inherent in standardized testing, Yale’s Dean of Undergraduate Admissions and Financial Aid, Jeremiah Quinlan, echoes the sentiments of Dartmouth’s Admissions Office that tests can actually aid diversity efforts. In an interview on February 22, 2024, Mr. Quinlan stated, “The entire admissions office staff is keenly aware of the research on the correlations between standardized test scores and household income as well as the persistent gaps by race. Our experience, however, is that including test scores as one component of a thoughtful whole-person review process can help increase the diversity of the student body rather than decrease it.”

The move by Dartmouth, Yale, Brown, Harvard, and Caltech to test-required admissions doesn’t sit well with some. Citing studies showing that standardized testing requirements serve as barriers to opportunity for students of color, Pell Grant recipients, women, first-generation-to-college students, and students with learning differences, proponents of test-optional admissions are dismayed by claims that standardized tests actually enhance diversity by helping the applications of academically-disadvantaged students.

They maintain that the equity-based thinking that drove a 13% increase in the adoption of test-optional policies by four-year schools – including the University of Chicago– between 2014 and 2019 remains as valid as ever: when schools require SAT or ACT scores, students that cannot afford personalized instruction in an $895 prep course or time away from jobs and family responsibilities to study may be deterred from applying at all.

Opponents of testing requirements worry that a perceived condemnation of test-optional policies by the Ivies, which wield significant influence in both the academic community and in the realm of public opinion, will put pressure on other institutions to “keep up” by reinstating test requirements, undoing the equity benefits gained when most schools went test-optional in 2020.

Moreover, critics question the philosophical underpinnings and validity of the metrics used to measure student success in the Opportunity Insights study cited by Dartmouth, et al. to show the predictive value of the SAT.

Opportunity Insights tracks the post-college outcomes of “reaching the upper tail of the income distribution, attending an elite graduate school, or working at a prestigious firm (e.g., highly ranked hospitals, universities, research institutions, and firms in law, consulting, and finance)” in addition to first-year GPA to gauge undergraduate academic success. To some, this narrow measure of student success smacks of capitalist elitism, tied as it is to big money, exclusive graduate programs, and employment by “top” firms that often do the least for the public good. By this standard, students who go on to work in education, the nonprofit sector, or join the Peace Corps would be deemed unsuccessful.

The study does not include student contributions to the undergraduate campus community including achievement in art, theater, athletics, student newspaper, student government, student clubs and affinity spaces, and campus activities in its definition of success. This strikes a sour note with students, who feel that defining student success in such a limited way runs counter to the stated admissions policies of Ivy League and other highly-selective institutions, which claim to employ a “holistic approach” that weighs all facets of an applicant’s character and accomplishments.

A member of the junior class (who would only comment on condition of anonymity because she does not want to jeopardize her chances of admission to an Ivy League school) says that she feels disheartened by both the reinstatement of SAT requirements and the reasons behind it. “All these schools claim that they look at students holistically in the admissions process, and that they put weight on extracurriculars, service, and your leadership qualities, then it all goes out the window once you get there because apparently you are only going to be valued by grades and how much money and corporate prestige you end up with.”

Bowdoin College, which was the first school in the nation to eliminate standardized testing requirements and has been test-optional since 1969, offers another view of student success. According to Bowdoin’s Senior Vice President and Dean of Admissions and Student Aid, Claudia Marroquin, although GPA and post-college employment, graduate school enrollment, and fellowship attainment are valuable measures of student success, so are metrics like student retention, student satisfaction, and student participation rates in volunteer service, service learning, research with a faculty member, internships, study abroad, and leadership in student organizations while at Bowdoin.

Ms. Marroquin also observes, “There is no way that an SAT or ACT score could possibly predict or measure student success when it comes to life skills or something like the ability to function on a team or the ability to develop a code of values or ethics. While future employment is certainly a goal of students once they have graduated from college, the college experience is so much more than a student’s first job or the name recognition of a company. At Bowdoin we firmly believe in our students having meaning and purpose in their lives – both professionally and personally. Reducing the College experience to employment at ‘elite’ companies or an income is simply wrong in my opinion.”

The repudiation of test-optional policies from Dartmouth, Brown, Yale, Harvard, and Caltech deals another blow of uncertainty to college applicants who are already reeling from the disastrous roll-out of the new FAFSA form, the recent Supreme Court decision ending affirmative action, and the switch to the digital-format SAT in March. Colleges and universities are also feeling the pressure of the uncertainties in the admissions landscape, which may contribute to their flip-flopping policies.

Some observers believe that media commentary–and especially David Leonhardt’s widely-read New York Times article “The Misguided War on the SAT”–-has mischaracterized the findings of the Opportunity Insights study, leading to a public perception that standardized testing requirements equate with unflinching standards of academic excellence. Therefore, when Dartmouth cited the study as the basis for reinstating testing requirements, other highly-selective institutions began to worry that retaining the test-optional policies they had recently touted might make them appear less rigorous by comparison.

For instance, when Caltech extended its test-blind policy in July of 2022, Caltech professor and chair of its first-year admissions committee, stated, “A consensus has developed among faculty and professional staff involved in admissions … that numerous other key attributes of applications serve as stronger indicators of the potential for student success here.”

On April 11, 2024, just hours after Harvard announced its reinstatement of test-required admissions, Caltech changed course, issuing a brief statement reinstating standardized testing requirements, stating simply, “We think it is critical that our admissions office and the faculty who are reviewing applicants have available to them all the information that could shape their understanding of a prospective student’s readiness for our rigorous academic programs.”

Harry Feder, the executive director of nonprofit advocacy group called FairTest that opposes standardized testing, chalks Caltech’s abrupt reversal of its test blind policy on April 11—just hours after Harvard’s announcement that it would reinstate test requirements—to old-fashioned FOMO. “They were nervous about the competition at their top level of admissions,” he told Inside Higher Ed on April 12. “This is not based on some new academic data that takes a deep look into how test-optional has gone for them … it’s about reasserting their commitment to high academic standards, which their peer institutions have clearly established one cannot do without test scores.”

Meanwhile, lost in the hullabaloo about the predictive value of SAT scores is what and whether schools stand to gain by reinstating testing requirements.

First, it is not clear whether overall “student success” has declined under test-optional admissions. Opportunity Insights has not yet responded to Spyglass’s request for more information about data comparing the total number or percentage of “unsuccessful” students in the current test-optional environment to the pre-pandemic, test-required period.

Second, schools have traditionally admitted a cohort of students—including recruited athletes, students from academically-disadvantaged backgrounds, and legacy admissions—under more flexible standards that include lower test scores. Unless schools that reinstate test requirements plan to only admit students with scores that correlate to “student success” as defined by Opportunity Insights, test-optional policies simply empower students to submit scores (or not) based on whether they help round out an academic profile, and may remove barriers to opportunity.

All of this news and noise around testing policies makes navigating the turbulent waters of college admissions trickier than ever. Luckily, the advice that Westridge College Counseling already provides to students about standardized testing ensures that Westridge students are well-positioned as policies evolve.

Commenting on the recent testing policy changes by Dartmouth, Yale, Brown, Harvard, and Caltech, Dr. Monique Eguavoen, Westridge’s Director of College Counseling, says, “These announcements reaffirm the advice we provide students about standardized testing; we already encourage all students to sit for one official standardized test. Why? For two reasons. (1) Many selective institutions admit more students with test scores within a specific range (it’s what we refer to as a testing advantage) and (2) situations like these, as admission policies for institutions evolve Westridge students are still prepared to apply.”

Dr. Eguavoen acknowledges that “we will have to wait and see in the coming weeks, months, and years if more colleges and universities change their current test optional policies.” Still, she reminds us “that for many institutions, students can continue to choose if they want to apply test optional or not – and it is important to note, students can be admitted to selective institutions as test optional applicants!” and also notes that she is “hopeful that most schools nationwide maintain their test optional status because . . . students are more than just a representation of their test score.”

For most college applicants, however, the recent rejection of test-optional policies by elite universities makes the intellectual knowledge that most schools remain test-optional feel like a technicality; there is no denying the outsized influence that a small cadre of Ivy League schools exerts over the broader college landscape. Even for students that don’t plan to apply to test-required schools, the announcements by Dartmouth, Brown, Yale, Harvard, and Caltech do make it feel like the importance of test scores has suddenly sky-rocketed.

Khan Academy SAT prep, here we come!

![Dr. Zanita Kelly, Director of Lower and Middle School, pictured above, and the rest of Westridge Administration were instrumental to providing Westridge faculty and staff the support they needed after the Eaton fire. "[Teachers] are part of the community," said Dr. Kelly. "Just like our families and students."](https://westridgespyglass.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dr.-kellyyy-1-e1748143600809.png)

Joe LeTaxi • Apr 17, 2024 at 9:25 am

I get the impression the author doesn’t understand the meaning of “elite.” Elite institutions graduate the people who are more likely to solve financial crises, cure cancers, discover novel forms of energy, and basically advance human civilization.

The people capable of facing these challenges are ultra-high achievers. In other words, the elite institutions should be reserved for the elite, or the magic will be lost.

School teachers and folks who make a career out of serving in the Peace Corps don’t need to take chairs from people who are capable and expected to go on to head august institutions. Obviously not everyone who stands an elite institution to achieve greatness, but that is the goal.

Admissions officers at highly selective schools primarily are looking for three things: dedication (often demonstrated by high-level achievement at sports and arts), social skills (demonstrated by other extracurriculars) and intelligence (most objectively demonstrated by test scores that stand out from their peers).

There are plenty of good and excellent colleges and universities. Let’s reserve the elite institutions for the elite achievers. A classroom filled exclusively with extremely bright individuals is a special thing. Let’s not destroy this opportunity that only really exists at a handful colleges and universities. If a student doesn’t want to submit test scores, there are still more than a thousand schools from which to choose, some still considered “elite.”