“Do you have a pad?” one classmate not-so-quietly announced just moments into B Block History. Before I could respond, three other students had already pulled out a colorful array of various pads (and a bonus tampon).

It’s not exactly uncommon for Westridge students to openly discuss or reference menstruation. Whether it’s discussing female pleasure in chemistry class or passing by the condom and dental dam bowl in the Human Development office, little is off the table when it comes to conversations around sexuality. Part of that might be attributed to the all-girls aspect, but another part is the formal sex education that occurs in the Human Development program for grades seven through twelve.

“I think [sex education] should happen at a young age and that it’s not about sex necessarily. Sex is part of sexual education. But sexual education is really about the human body and understanding the human body,” said Ms. Gigi Bizar, who teaches seventh grade history and 10th grade Human Development.

But what exactly constitutes a comprehensive, legitimate, and impactful sex education? Should an adequate sex education be based in biology? In pleasure? In sex’s social-emotional aspects? And what constitutes meaningful sex-ed at Westridge?

Sex-Ed at Westridge

Human Development, or HD, is a required class in Middle and Upper School that meets once every six-day rotation. Through lessons, discussion, and activities, students learn how to navigate the social, emotional, and physical changes they’re experiencing at these grade levels. Although Westridge’s Human Development Coordinator Ms. Emily Mukai teaches a number of these classes, many are additionally taught by English, history, and science faculty members, who, as of last year, must apply for the position.

But the Westridge HD program, and more specifically, sex-ed, seems in a near-constant evolution. Frequent turnover in HD coordinators as well as external issues that call for additions to the curriculum, like the current fentanyl crisis in Los Angeles, often create discrepancies in content from year to year.

Ms. Mukai, Westridge’s fourth HD Coordinator to hold the position in the last 10 years, recognizes the need for a program that is both responsive and consistent. One of her initial changes was to shift the bulk of sex-ed from the seventh to the eighth grade, believing that eighth grade was where these concepts were more likely to become applicable to students.

“Seventh grade is kind of the prequel. We go in very in-depth into what the female cycles, and not just from the perspective of pregnancy, but, also understanding…how a person with female anatomy might experience their cycle. And then just sort of like getting them comfortable with saying the word vagina,” Ms. Mukai said.

In eighth grade, Ms. Mukai bases the curriculum on what students need to know about sex and their bodies to be both safe and comfortable. Topics range from the female cycle to contraceptives to sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Last year eighth and ninth graders received the same lessons in order to catch up the grade levels.

In 10th and 11th grade, the curriculum is primarily pleasure-oriented and contains more info about LGBTQ+ sex education. The most notable aspect of these units is, for many students, watching the Netflix show “Principles of Pleasure,” which unabashedly dives into women’s pleasure. “I think it’s beneficial for people to know about it, so they are not walking into everything blind. And to not feel ashamed,” Noa K. ’24 said about the documentary.

“I was a little bit taken aback by how provocative it was and how empowering for a woman of that age. I think the kids got a lot out of it though,” Ms. Bizar said.

In 12th grade, the curriculum is slightly more fluid and includes a discussion of non-consensual sex, in which a sexual assault nurse is invited as a guest speaker.

“I think that the Westridge sex-ed is definitely better than [other] places,” said Bina P. ’24, one of the heads of Let It Flow, a Westridge club made up of many self-proclaimed HD lovers.

At other Pasadena private schools, approaches to sex education and curricula vary. Polytechnic School has a human development similar to Westridge. Students are required to take a Human Development class that meets once every six days. The curriculum also dives into sex education more fully in the 10th grade, spending ninth grade discussing identity and community. “I would argue that everything that we talk about in terms of identity and the way that we relate to one another connects with sexual health because everything that we learn about ourselves informs the choices and the interactions that we have with other people in more intimate ways,” said Stephanie Monteleone, the Human Development Coordinator at Polytechnic.

Conversely, Flintridge Preparatory School teaches sex education primarily in the biology classroom, looking at it from a scientific perspective. While the lessons come from a scientific lens at Flintridge Preparatory School, there is still room for creativity and progressiveness in how teachers present the information. “We do a lot of activities…a lot of dances about the human body, and [the students] make little shows and brain art on canvases. So there are a lot of ways we do it, but I think it’s not quite as traditionalist as some science classes have been in this world,” stated Hilary Thomas, who teaches seventh grade science at Flintridge Preparatory School.

Addressing Student Needs

Westridge has come a long way in attempting to address student needs. “I feel like [sex-ed] has been evolving…It’s cool to see how much evolution there’s been from being very cis-heteronormative, ‘don’t get pregnant’ to now. Now, we’re thinking about it from a big picture: we’re going to talk about pleasure, we’re going to talk about things that feel really taboo,” Ms. Mukai noted.

However, the current curriculum still leaves some students wanting, and even needing more, particularly when it comes to representation.

“[I wish we] talked about any other type of sex that’s not penetrative…we don’t need to tiptoe around [sex-ed],” said Dahlia V. ’24, one of the heads of the Let It Flow club.

“It really only seemed like we were talking about procreation and sexual penetration,” Grace W. ’26 echoed.

Many Westridge students believe that a comprehensive sex education curriculum extends beyond the typical, heteronormative conversations and would like to see more content that reflects those concerns.

Kaya I. ’24 also adds that a more representative sex curriculum is valuable for all students. “I feel like a lot of times, a heteronormative sex education doesn’t give people a realistic idea of what sex even is. Even if you are heterosexual, it’s important to know that other kinds of sex exist,” Kaya said.

Ms. Mukai mentioned that the new curriculum in Upper School is shifting to be more representative and expansive. “Now for 10th and 11th ,we’re starting to move into more pleasure oriented things and thinking about LGBTQ+ sex-ed… The questions are not necessarily: ‘What is sex?’ It’s more like the logistics of pleasure or logistics of safety.”

Some students hope that parts of the curriculum that perpetuate misconceptions also change.

“We went and we taught sixth graders about menstruation and whatnot…One of the things that was really disappointing was that [the teachers] perpetuated the myth of periods syncing up. It’s not a harmful myth, but it’s not true,” Bina said.

Other teachers and students believe that the curriculum needs more of a focus on consent and avoiding non-consensual sex.

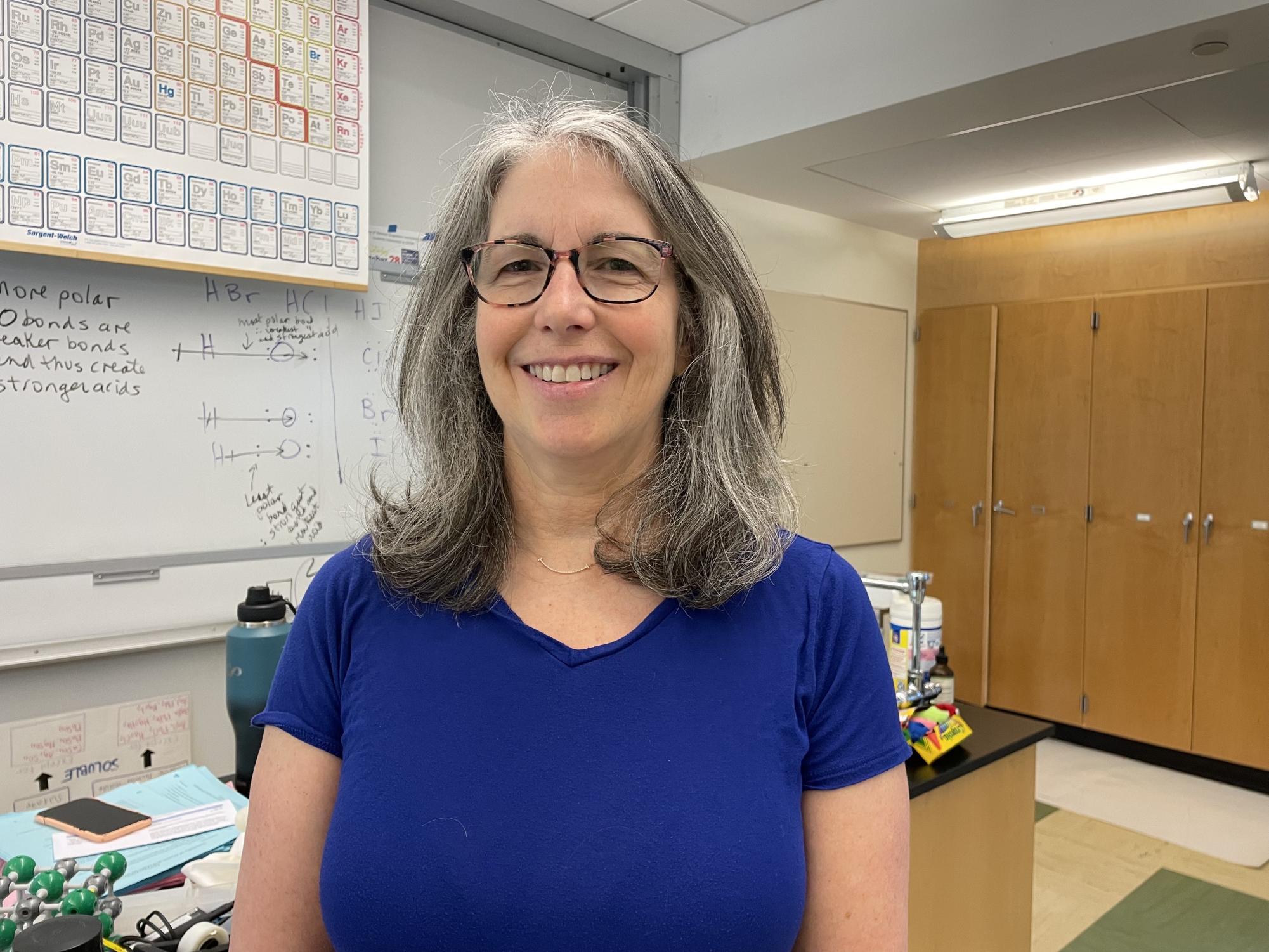

“[Westridge] is so good at so many things for young women. Teaching them about how to avoid non-consensual sex is really important. And I don’t know if we’re succeeding at it,” Upper School Chemistry Teacher and HD Teacher Dr. Edye Udell said.

Dr. Udell noted that a comprehensive sex education should include more information on sexual violence, especially earlier on. At the moment, these conversations take place in senior year. “At a girls’ school, we’re all about empowering women in many different ways. I think that sexual violence, unfortunately, is one way in which many women are disempowered later in life. So if we can help empower our students, they can go out and help empower others,” she said.

There is also a call for a more balanced approach that instills awareness while empowering students to navigate these issues confidently. Dr. Udell also emphasized that as a teacher, it is important to ensure that students feel safe and empowered rather than fearful when discussing issues like sexual violence, representation, and pleasure. While these are often discussions that lead to discomfort, Dr. Udell acknowledged the impact of presenting information in a way that “instills the right amount of fear with understanding and empowerment.”

Moving forward, faculty members, students, and coordinators also wonder how topics around sex-ed could be effectively addressed outside of the Human Development classes. For example, conversations around consent often come up in English and science classes.

Discussions around sex and sexuality aren’t limited to the HD classroom, but supporting the conversation across the school curriculum can be challenging. “We can’t just teach these subjects in this one tiny little block because all that we can do is plant this seed and then hope that in other areas, it kind of bleeds out… I think giving students and teachers language to actually be able to [talk about it] is really important. I think there’s definitely an opportunity there,” Ms. Mukai said.

Dr. Udell added that incorporating sex-ed into other classes could help make the topics feel more natural. “[Sex-ed] shouldn’t only be the responsibility of human development. Because when you’re in a class where the focus is having uncomfortable conversations or societally non-typical conversations, it’s not natural… I want to know from students: how do we create a system where it becomes more natural?”

![Dr. Zanita Kelly, Director of Lower and Middle School, pictured above, and the rest of Westridge Administration were instrumental to providing Westridge faculty and staff the support they needed after the Eaton fire. "[Teachers] are part of the community," said Dr. Kelly. "Just like our families and students."](https://westridgespyglass.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dr.-kellyyy-1-e1748143600809.png)