With The House on Mango Street opened to the last night’s assigned pages, Spyglass staffer Amanda S. ’26 watched others in her 9th grade English class discuss the novel effortlessly. Even though Amanda knew that active participation was expected in this particular class, she felt her vocal cords stiffen in her throat, self-doubt and fear gnawing away in her head. The clock was ticking, and her teacher politely invited anyone who hadn’t shared to do so.

With five minutes left, a classmate turned towards her and piped up, “Amanda still has to go.” As all eyes shifted toward her, she blurted out some random idea she had circled in her annotations. Her classmates nodded supportively, but even after she’d participated, she still felt anxious.

For Amanda and many other students, verbal participation in classroom settings can cause panic and anxiety. The fear of making a mistake or facing judgment from one’s peers can be a stress trigger at every level of participation, whether it’s fishbowl discussions, presentations, or even asking a question. Amanda attributes her anxiety to the fear of judgment.

Nina K. ’26 recalls having similar experiences to Amanda. She says, “I’ve always cared a lot about what other people think, so I’m worried about if other people judge me, or if they’re like, ‘Oh, that’s not right. You’re not meant to be here.’”

There are many reasons students might struggle to participate: social anxiety, their upbringing, or dynamics within the class. Julia W. ’24 says, “I feel like we all grew up in different environments that fostered different types of people. And I feel like my upbringing did not promote social activities. That wasn’t important in my childhood.”

Lilian L. ’25 says, “I was a very socially awkward kid, and it didn’t help that my parents weren’t very supportive with my social awkwardness. So that kind of contributes to how I engage in a classroom environment.”

Though class participation can be challenging, not participating can negatively impact students’ grades. Melina H. ’26, another student who has struggled with verbal participation, says, “I do feel pressure [to participate in class] because even when I don’t know what I’m doing and I don’t want to speak up, I still want the participation points.”

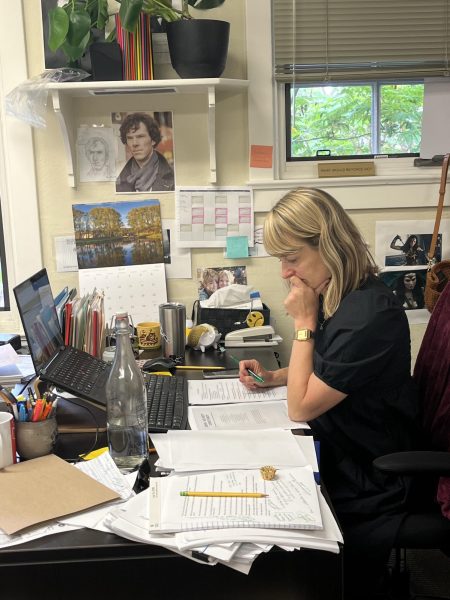

(PC: Eliza W.)

At Westridge, class participation is often an expectation, if not an explicit course requirement, particularly in humanities classes which tend to be discussion-based.

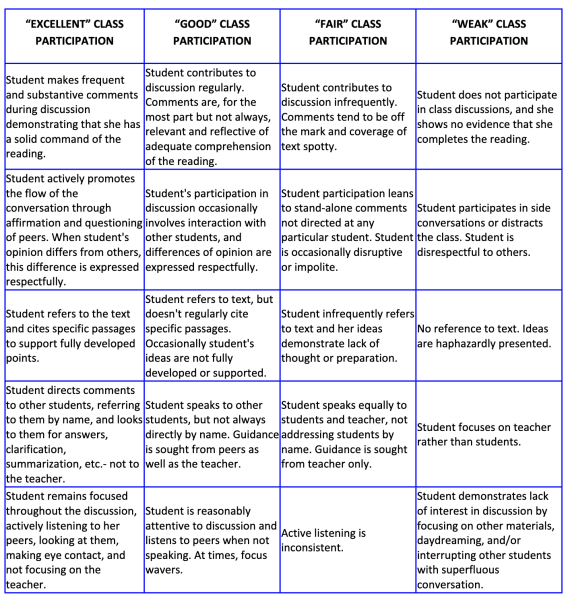

For those teachers, participation is generally defined by verbal contributions in a discussion setting. A rubric for “excellent,” “good,” “fair,” and “weak” class participation is provided in several Upper School English classes. Four of the five boxes in the column associate participation with speaking aloud.

Upper School English Teacher Molly Yurchak says, “I think the most effective way to learn is by teaching others. So class conversation is really the way we work out our ideas and teach ourselves and others.”

Other English teachers have included non-verbal ways to participate. In Katie Wei’s English II syllabus she writes that “strong participation consists of preparedness for class (materials, homework, any other required elements), engaged listening, focus, positive attitude, and thoughtful contributions and engagement.”

In math and science, classes are typically not as discussion-based as the humanities. Barbara Chabot, a Middle School Science Teacher and Chair of the Upper School Science Department, says that as a whole the science department does not have a universal policy or philosophy regarding participation. In her classroom, Ms. Chabot, who does not grade participation, values collaboration with one’s peers and contributing to small group discussions. “The way that I have figured out to maximize everyone’s participation is to do it in these little groups and just have it be an ongoing thing. And you can’t really opt out of it that way. But also, it’s not as high stakes,” she says.

Similarly, Leah Dahl, Upper School Math teacher and Chair of the Upper School Math Department, states, “Participation in my classes is not graded, but it is something that I often will write about in comments or something like that just because I feel like it is a part of the class, whether or not it’s a graded part.” She also believes participation can be verbal, but it can also entail writing notes for your group or asking questions.

The standard for “good participation” isn’t always clear to students. Willow N. ’25 says, “I think that a lot of times, especially in English, people will just say stuff to say stuff, even if it’s not valuable, like sometimes almost restating what other people are saying just to get extra participation points.”

With the abundance of definitions and philosophies among subjects and even between teachers, evaluating participation can seem subjective. How do teachers measure something like a student’s engaged listening or promotion of the flow of the conversation?

Finding a healthy and equitable middle ground for participation has proven difficult for students and teachers alike. Over the years, many departments have reassessed the way in which they grade participation. Ms. Yurchak acknowledges the struggle of finding an equitable method. She says, “For years, I made class participation…30% of my grade and 40% of my overall grade because I kind of do think it’s that important. Then the faculty read a book called Grading for Equity, which asks us, among other topics, to really think about ‘how does this discriminate against students who have a harder time [participating].’ I totally went the other way.”

Two to three years ago, Yurchak reduced participation not even 1% of a student’s grade but found that following the implementation of that policy, certain students never spoke again.

Now, Yurchak has found a balance, weighing verbal participation, but not as heavily as she did originally.

Some teachers in the History Department provide a discussion board alternative for verbal participation. Willa Greenstone, Upper School History Teacher, states on her Canvas class page, “I want to encourage anyone who is not comfortable with participating during class discussion to take advantage of this alternative option.” This space is also offered in several other English and history classes. Sometimes the option is not presented as an alternative, but rather, an additional space to share ideas.

Ms. de Grijs, another Upper School History teacher who struggled herself to participate in her high school and college classes, utilizes a discussion board. “I always want to create an atmosphere where if kids want to participate, that’s great. [But] I never want them to feel like they’re compelled to have to,” she says. So for her classes, verbal participation can only raise someone’s grade, not lower it.

Many teachers have also focused on including other in-class activities—whether it be quick writes (close readings) or group presentations. James Evans, Director of Teaching and Learning and Upper School Art History teacher, shared one thing that has successfully worked in the past—it’s called a silent discussion. In this activity, students individually and silently write down their thoughts, then move to the next person’s station and respond to that person’s thoughts. Methods like this aim to promote the idea that every student has interesting and valuable thoughts, even if they struggle to articulate them verbally.

In support of a more equitable class model, James Evans says, “I want people to feel like they have value to offer the class and that there is a purpose to participate, not to score points, or not just to be seen to be participating, but to have a sense of communal learning.”

Alternatives like silent discussion or discussion boards can create a space for both students who flourish verbally as well as those who thrive with paper and pen. However some classes have gone as far as eliminating verbal participation as a grading factor completely.

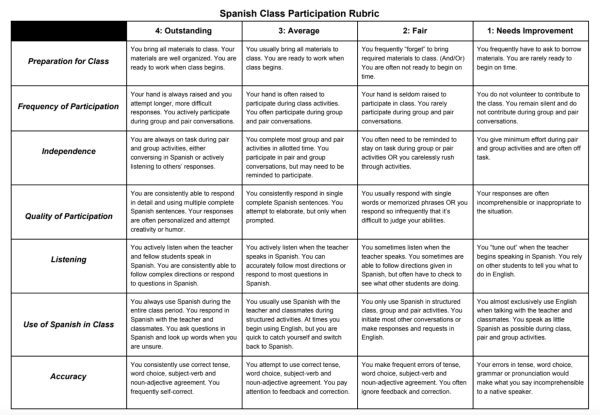

Vicki Garrett, Upper School Spanish Teacher and Spanish Department Chair spoke about how in her first 20 years teaching Spanish, she counted verbal participation as 10% or more of a student’s final grade. Upon first arriving at Westridge, prior to the pandemic, she shifted to a student self-reflection rubric to help her grade participation. The rubric states participation is preparation for class, frequency of participation, independence, quality of participation, listening, use of Spanish in class, and accuracy. But when the pandemic struck she reevaluated once again, ultimately settling on not grading verbal in-class participation.

She says, “For me, the purpose of [participation] that’s important is practicing the kinds of communicative functions that we would want students to be able to do successfully outside of the classroom.”

Beyond specific classroom practices, teachers additionally make efforts to speak with students who struggle to verbally participate, encouraging confidence and growth. Dr. Garrett explains her approach, stating, “I want to see if I can understand the cause or the reason behind [not participating].”

Ms. Dahl often suggests to her advisees who struggle to participate to take small steps, whether this is planning out ideas of what they want to say before class, setting goals of how often they should participate, or trying to be the first person to jump into the conversation.

While teachers have made efforts to reevaluate the way participation is defined, encouraged, and ultimately graded, even students who struggle to participate recognize the benefits of discussion. Self-described introvert Lilian L. ’25 said, “I know some students are much better oral learners, so I don’t think it’s fair to…completely take away discussions just to accommodate us.”

Some students additionally recognize that the expectations around participation have helped them grow as learners.

Yoko P. ’24, who described herself as a “non-talker in History class,” says that last year she decided to make a change. “I was just like, ‘You know what? I’m just going to participate in every class.’ And then I just started doing it, and it got so much easier. It became normal.” She continues, “When I used to not participate, it was a total choice I was making to be passive in the class. I realized I can just switch that. It helps your grade, it helps your confidence in the understanding of the material, it helps you feel more connected to your classmates and teachers.”

![Dr. Zanita Kelly, Director of Lower and Middle School, pictured above, and the rest of Westridge Administration were instrumental to providing Westridge faculty and staff the support they needed after the Eaton fire. "[Teachers] are part of the community," said Dr. Kelly. "Just like our families and students."](https://westridgespyglass.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dr.-kellyyy-1-e1748143600809.png)