Sorry Not Sorry: Why I’m Done Using the Reflexive Sorry

I’m done saying sorry. I mean if I break your leg, ruin your painting, or take the last burrito from the commons—sure, I’ll apologize. But what I’m talking about is the repeated and unnecessary apology. Sorry I dropped the football. Sorry I shut the door loudly. Sorry I made a joke nobody laughed at.

I’m fed up saying sorry for things I don’t mean. My mom has always pointed out to me how much I say sorry, and I’ve tried unsuccessfully to abolish it from my vocabulary. Coming to Westridge, I had high hopes of being unapologetic and bold-spirited, but even as I have been trying to hold myself to the no-sorry rule, I’ve noticed that many of the women around me apologize for things that they don’t need to be sorry for.

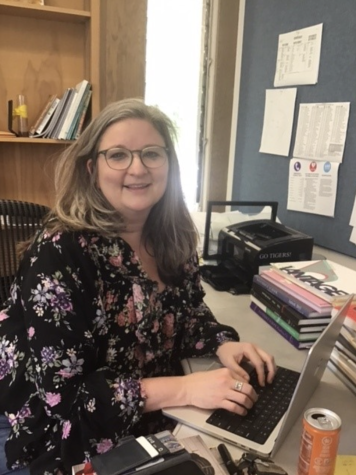

I talked to Dr. Lisa. LaFave, director of counseling and student support, about this subject, and she also felt that women and girls apologize too much. She shared a story with me of a student: “I was just in the Commons getting a drink, and somebody passed by close to me and she was like, ‘Oh, I’m so sorry’ when she probably meant ‘excuse me.’” This story is exactly what I’m talking about. We don’t even realize we’re doing it or that it’s an issue.

I had the opportunity to interview Head of School Andrea Kassar, and while we were talking, she said that the use or overuse of sorry is like a verbal filler. “Sorry can almost become a kind of verbal tic, the way that the word ‘like’ can be a filler.”

The overuse of sorry can actually muddy or confuse communication because it can be hard to tell the difference between an authentic apology and a reflexive apology. In a New York Times article about shifting our views on apologizing, Kristen Wong put it best: “Some apologies are meant to repair a relationship, like when you forget to pick up your friend at the airport. Some apologies show respect, like when you submit a report to your boss and it’s a day or two late. And some apologies are simply meant to smooth out a conversation.”

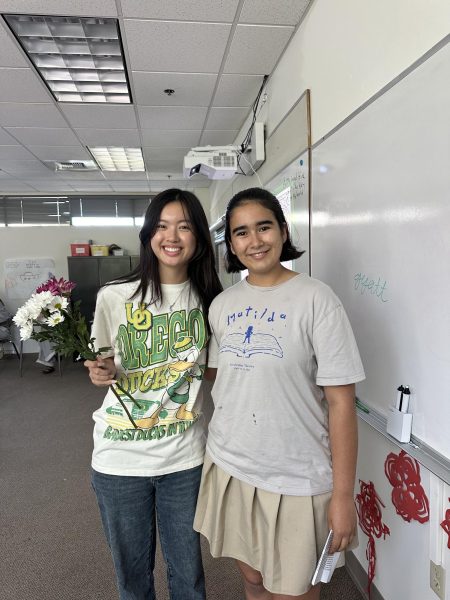

Fair enough, but I wanted to ask my peers just what they were apologizing for. When I talked to Sophie G. ’29 she said, “[I’m worried that] if I do something wrong and I don’t say sorry, I’ll be scolded.”

I completely understand this fear of what might happen if you aren’t polite or don’t come off as nice. Xann D. ’29 echoed this sentiment and further elaborated: “[Girls] have to come off as nice or innocent, so you have to say sorry. Well—you don’t have to, but that’s the stereotype.”

That is exactly the mindset and stereotype I myself am trying to combat. Part of that process for me is being in an environment like Westridge where my loud, smart, and brave self can come out without fear or judgment.

Ms. Kassar, who has always been involved in girls’ schools—whether as a student, teacher, or leader—believes that giving girls spaces to express themselves fully is part of what makes girls’ schools so powerful. “Physically, vocally, girls are allowed to be in a space that doesn’t have a gaze on them from the world,” she said. “I think all of that leads to something that is certainly—I don’t know if I would say unapologetic—but certainly less apologetic. And the practice and the confidence that you get from being in an environment like that, for years, is something that you take with you for the rest of your life. And I know this because I went to a girl’s school for 13 years.”

Being in an all-girls school, we are raised to be upstanders and believe in ourselves; we are trained to raise our hands and pick the seat up front. Even after being here for only a year, I am finding myself to be loud and bold in ways I wouldn’t have been if I were being constantly shushed by boys at my old school.

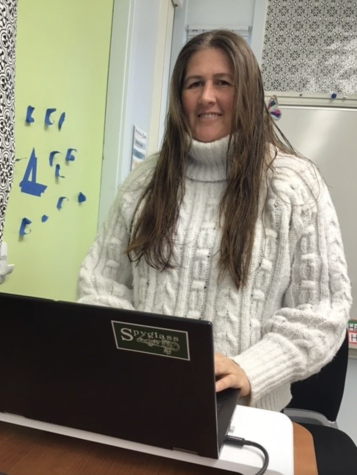

What I’m trying to say is I have really found my voice over this year, I’ve been writing articles about my opinions and I’ve been trying to succeed in math even if it’s not something I’m interested in. The all-girls environment is something which we often take advantage of and which I hope to savor while I’m here. Bonnie Martinez, Upper School Dean of Student Support, spoke about her own goals for her students. “We are trying to teach our girls to be strong and unapologetic and in a very appropriate way.”

What do we do about it? Experts encourage us to be self aware and acknowledge what we’re saying and why we are saying sorry. Kristen Wong gives advice to women all over the country. “Ask yourself why you apologize,” she says. “Instead of cutting out your apologies, pay attention to how you feel when you apologize.”

When I spoke with community members, both students and adults, one suggestion kept coming up: We need to have these conversations and confront this issue. Because the worst thing we can do is pretend it doesn’t exist.

Farrell Heydorff, Dean of Student Activities, is doing the opposite of pretending it doesn’t exist with her middle school girls’ volleyball team. She is actively working towards eradicating the reflexive sorry from their vocabulary. “Anytime anyone’s learning a new sport or anything like that when I’m coaching, I set a rule at the very beginning that they’re not allowed to say ‘I’m sorry’ when they mess up. They say ‘I’ve got the next one.’” I think what Ms. Heydorff is doing is amazing. She’s not only acknowledging it and bringing it into the light but also doing something about it.

Ms. Kassar had a similar point of view, but took it even further. She referenced the book Under Pressure by Lisa Damour, who wrote: “It’s time to change how we talk about how girls talk. Rather than critiquing how girls speak, we might recognize that they intuitively deploy a sophisticated set of linguistic strategies to turn people down without hurting feelings, or damaging a valued relationship. But when it comes to how girls speak, let’s move from criticism to curiosity.”

This changed my perspective. Instead of just scolding girls and saying, “Hey, you should stop saying this,” we need to question the entire system and ask, “Does sorry still serve us?”

For me, the sorry I use in my day-to-day life is less of an actual apology and more of a way to lessen or diminish what I’m saying. It’s a way of making me sound unsure of myself and not rude; in many ways, I’ve been socialized to not sound entitled or “too” confident. When I raise my hand and say, “Sorry, I’m not sure if this is correct, but…,” I’m projecting humility—but why do I feel I need to apologize for my own learning process?

What I’ve discovered is that my use of the word sorry is really a reflection of my own insecurities. I admit, I often worry about what others think or say about me. I often find myself afraid that I’m coming off as “rude” or “snobby,” and I’m really trying to separate myself from those feelings of insecurity.

I know I should be able to be loud and confident without worrying about what others think. In the future when apologizing, I will try to think of why I’m saying sorry and how it truly makes me feel because I don’t want to put myself down for no reason.

Even more than that, I’m working on not just being unapologetic with my speech patterns and reflexes, but I’m trying not to worry so much about what others think of me, which is actually harder. It’s easier to break a speech pattern than to rewire how you think entirely. But that’s where I’m going to start.

Mena is a sophomore. If she isn't bothering her dog, you can find her working on a crochet project, or in the library, stealing all of the free bookmarks....

![Dr. Zanita Kelly, Director of Lower and Middle School, pictured above, and the rest of Westridge Administration were instrumental to providing Westridge faculty and staff the support they needed after the Eaton fire. "[Teachers] are part of the community," said Dr. Kelly. "Just like our families and students."](https://westridgespyglass.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dr.-kellyyy-1-e1748143600809.png)