Op-Ed: It’s time to stop pretending body positivity is positive

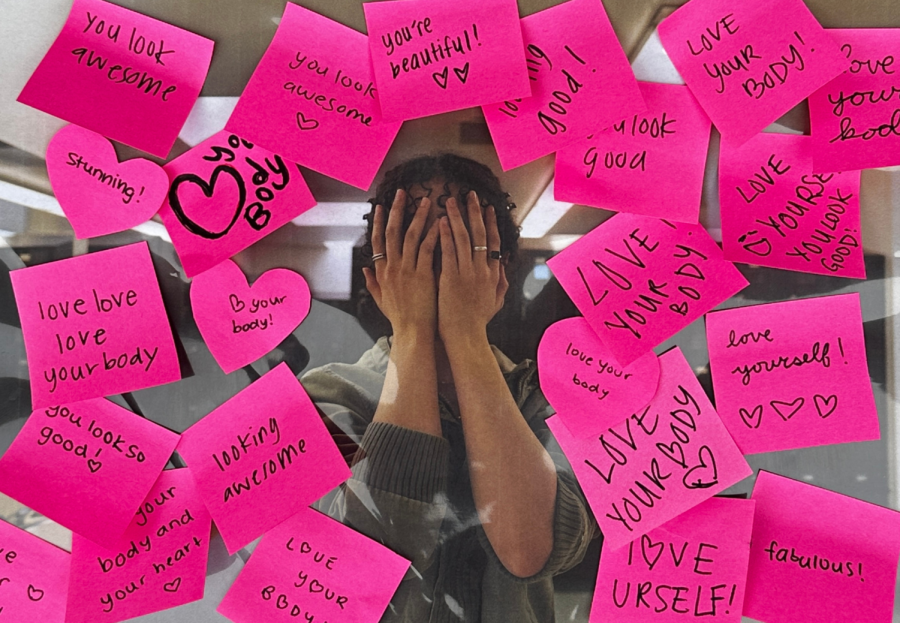

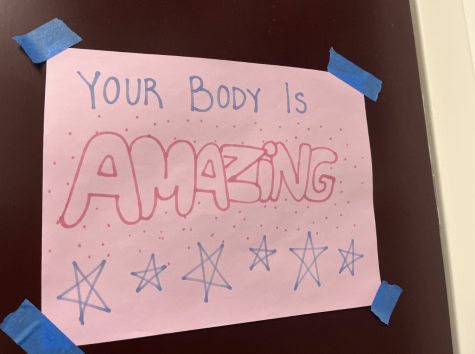

In my time at Westridge, I’ve grown to resent no event more than the week dedicated to loving one’s body. During past “Love Your Body” weeks, seemingly harmless small pink posters covered in messages would abruptly emerge in campus bathrooms, reminding us that “it’s okay not to have a thigh gap” or to “love your stomach.” Such messages, while cheesy, are intended to be encouraging.

And positivity should make one feel positive, no?

But more often than not, these messages of self-love—whether shared on social media, news outlets, or annoyingly pink posters—contradict the message they aim to promote: positivity. What should be a brief glimpse in the mirror to adjust my hair becomes several minutes as I read each poster, my attention now drawn to my legs and torso. As my theoretically private moment becomes invaded by an assault of toxic positivity, I begin to feel nauseous. Leaving the restroom, I’m no longer stressing about my upcoming test. Instead I’m fixated on the jiggle of my thighs as I walk, trying to suck in my stomach which now seems immensely bloated from lunch.

I know these are well-intentioned efforts, but how can I possibly feel positive about myself when I’m surrounded by the laundry list of body image issues, a three-paneled mirror, and the bombardment of posters listing out potential flaws to obsess over not obsessing?

Additionally, every poster feels like it’s specifically targeting a body image issue. Thigh gap, flat stomach, clear skin, big boobs, small boobs…I don’t want and/or need to be reminded of my adolescent reckoning with body image. I feel like a fool already, having wasted so much time caring about how I looked and constricting myself to rigid regiments of exercising and eating when the messages glibly suggest that all I had to do was “love myself” or “accept this trait.”

Putting aside my own issues with the posters, the body positivity movement as a whole cannot create long-lasting positive effects because it often glosses over the realities of body dysmorphia and eating disorders. It instead packages them in cutesy and widely accessible infographics and messages that reduce the causes of both of them to a lack of self-love.

According to the National Centre for Eating Disorders, “Eating Disorders are a response to stress. Eating disorders don’t just happen; they are triggered into life most often at a time of stress such as when parents divorce or someone changes schools. It starts as a small crisis of coping when a person feels vulnerable and might turn to dieting as a way to feel better or more popular. Hidden inside, we often find an exaggerated need for control, not just of feelings, but also of how other people feel about us.”

The blunt and cheery displays of body positivity or see-through representation can often trivialize those issues. And while body positivity does not claim to fully solve or combat why these problems occur in the first place, increased affirmation feels like a static and unproductive solution to eating disorders, an issue that quickly intensifies.

This year, Peer-to-Peer, responsible for hosting and organizing the “Love Your Body Week” events at Westridge, shifted the event’s name to “Everybody for Every Body Week.” They also reexamined their philosophy around the event, stating their new goals would, “focus instead on including all humans and the pressures they feel in their bodies to look or be a particular way.” The change reflects a step forward and an acknowledgment that the week’s emphasis on positivity felt problematic to much of the student body. But the event, which took place February 6-10, played out similarly to previous years, just in a slightly toned-back manner. Nobody hung any posters, but a town meeting centering on body image occurred, arguably each year’s most problematic part of the event.

Although most students don’t go up to speak at town meetings with the intention of harming their peers, when somebody with an eating disorder speaks about their experience or their recovery, it can trigger other students with disordered eating to compare themselves or their trauma.

But I also understand that some students want and/or need the space to further discuss their experience with body image and eating disorders on campus, and I agree that under certain circumstances, this discourse is beneficial and necessary. Sometimes hearing that someone is going through or has gone through the same thing as you makes the experience feel less alienating or scary. But like the discussion of any triggering topic, it’s hard to make sure the audience is comfortable with and prepared to hear that information. That’s why school-wide discussions and posters cannot and will not work. They do not ask for the consent of their audience.

I instead propose that we as a school embrace a more conscious emphasis on body neutrality. While neutrality does not appear to be an exciting or flashy solution, it is the only way to create a safe space for all students.

According to Maria Sorbara Mora, founder of Integrated Eating Dietetics-Nutrition PLLC, “Body neutrality has its foundations in what your body does, not how it looks. That shifts the focus from controlling it to finding gratitude for it. What does your body allow you to do: take you on adventurous walks, hug your loved ones, experience a sumptuous meal, etc. Body neutrality communicates that our bodies are vehicles—that when treated with care—can become vibrant vessels for life to move through them.”

I know that I will probably never look in a mirror and fully “love my stomach,” so I am trying to otherwise accept my body through this idea of neutrality. My body lets me write this article, my body lets me perform on stage, and most importantly, my body lets me be around the people I love, three aspects of my life I’d be nothing without.

And as we move forward as a school, I challenge us to think more about valuing a person’s character and passions, rather than the way their body appears. We can use this week in a much more positive manner to showcase what bodies can do. Lunchtime activities where students who love cooking get to cook for their classmates or students who love drawing get to do quick drawings for their classmates are both easy and accessible ways to begin this transition. The more we begin deemphasizing the body and emphasizing the person, the closer we come to actually loving ourselves.

Eliza is a senior and the Editor in Chief of Spyglass this year. This is her fifth year on staff and her third year as an editor. Outside of Spyglass,...

![Dr. Zanita Kelly, Director of Lower and Middle School, pictured above, and the rest of Westridge Administration were instrumental to providing Westridge faculty and staff the support they needed after the Eaton fire. "[Teachers] are part of the community," said Dr. Kelly. "Just like our families and students."](https://westridgespyglass.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dr.-kellyyy-1-e1748143600809.png)