Eighth-Graders Question Sherman Alexie’s Place in American Studies Curriculum

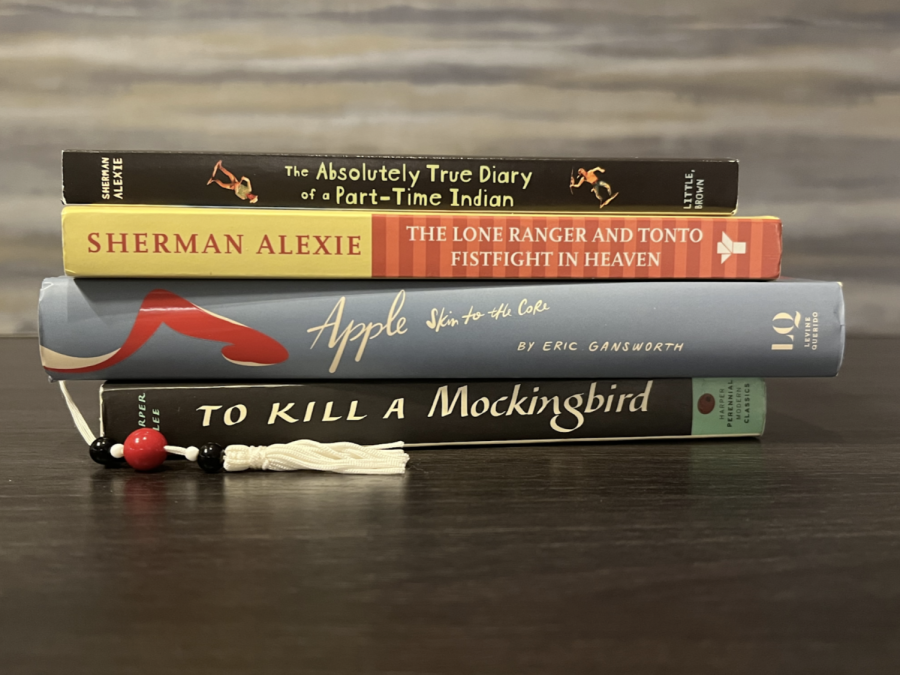

Pictured are three books in the eighth-grade curriculum that are commonly challenged in schools, as well as Apple: Skin to the Core, a book being considered as a replacement for The Lone Ranger.

Clustered together in the Westridge Mudd Pit, two sections of eighth-grade students started their quarter two American Studies unit by gathering to discuss the curriculum, specifically, why two books by Sherman Alexie are used. Alexie has faced criticism since 2018 when he released a statement apologizing for the sexual harassment allegations against him.

In the Eighth-Grade American Studies program, students study two of Alexie’s novels: Absolutely True Diaries of a Part-Time Indian and The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight Into Heaven. Since the allegations surfaced and his subsequent apology, Ms. Oseran, the Eighth-Grade English Teacher, and Ms. Irish, the Eighth-Grade History Teacher, invited students into a discussion about Alexie’s presence in the curriculum.

One eighth-grader, Adelaide C., didn’t particularly like the author but was willing to hold off forming an opinion until she read The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight Into Heaven. “I think that Westridge should have clarified to us who exactly Sherman Alexie was and made a broader acknowledgment of what he has done before making us read the book. While I understand that the previous class last year was okay with it, they should go in with the mindset that the grades are a little bit different and our grade might not appreciate it being sprung upon us. Do I think that we should not read his book at all? No, because I do think we were able to have good discussions around the topics that the book provided us.” Her opinions are similar to the ideas presented in the article, and most importantly, she agrees that having a conversation around the situation in the first place is vital.

In previous years, the class discussions acknowledged that students felt uncomfortable, but students were still willing to use his books. However, this year’s eighth-graders had a much stronger reaction. “We knew it was problematic,” Ms. Irish said. “I think we were surprised, actually, how problematic it seemed for students.”

One eighth-grader, T L., first learned about the author from their older sister, a current Westridge sophomore. For T, like many others, purchasing the books was a point of contention. “I had assumed the teachers would have told us if they were going to have us read his books. It wasn’t like they were provided and had been reused for years and had been school books that had already been bought. It’s a little different when you’re asking us to buy a book that is directly supporting [what I consider] a bad author.”

In the discussion, the main concern of students was that a school like Westridge, which has based its mission around helping female and AFAB students empower themselves, is supporting an author who doesn’t fit that narrative.

Some students wanted to use second-hand versions of the books to avoid more profit for the author. Others would like to see the teachers replace his books completely.

“I hope we can switch to other books,” Caroline M. ’26 said. “We still need to learn about the indigenous experience, just not at the expense of forgetting about what he did. Especially because sexual harassment is a big issue in indigenous communities, it feels a bit ironic.”

“A lot of people said that we should look more into the artist’s work instead of the artist themself,” Lauren W. ’26 said. “If people are really uncomfortable with this situation, it’s important to respect others’ opinions. I think we should keep reading his books because he is an amazing writer and is especially helpful as a source to learn about Native American people.”

Ultimately, Ms. Oseran and Ms. Irish agreed to consider other replacements for Absolutely True Diaries of a Part-Time Indian and The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight Into Heaven. “Yes, we think Alexie’s books have a lot to offer in our exploration of the Native American experience, but as educators, we are often re-assessing our curriculum for a variety of reasons (student response being one of them),” Ms. Oseran said. “We will continue to consider other book options that might work as a replacement, and will make a change when we feel it is right for the curriculum.”

In response to student feedback, Ms. Oseran and Ms. Irish started a student book club to provide feedback on potential replacements for Sherman Alexie’s novels. So far the club has read Apple: Skin to the Core by Eric Gansworth. If used, it would likely be for English class. Even then, Ms. Oseran and Ms. Irish would still have to make the decision of whether or not to partially replace the books or stick completely to Sherman Alexie, something that will completely depend on the alternatives they are able to find.

Finding a replacement is easier said than done. “My concern about replacing Sherman Alexie is that there might not be a suitable alternative that checks all the boxes for what we need in eighth grade,” Ms. Irish said. “We need a book both for independent reading (the summer reading), and one that is conducive to close reading and analysis. We also need a book appropriate for the eighth-grade reader. There is a real possibility that if we put aside Sherman Alexie, we will have nothing to replace it with and then lose a Native American voice in our curriculum.”

Her caution about potentially losing a Native American voice isn’t unfounded either. Before The Absolutely True Diaries of a Part-Time Indian was picked up by the eighth grade, ninth-graders in the Upper School used it as a classroom text. However, the book moved into the eighth-grade curriculum instead. Although no new novel with an Indigenous author replaced it, Joy Harjo’s poetry is frequently used in the Upper School program. Other Indigenous authors, including Sherman Alexie, are included on a recommended summer reading list.

Asking students to grapple with problematic authors and texts is part of the learning process. When introducing the unit, Ms. Oseran shared an article by the New York Times that asks the question, “Do Works by Men Implicated by #MeToo Belong in the classroom?” The article examined how teachers and students discuss problematic authors. The article ends with a takeaway from a student. “The more we talked about [Sherman Alexie], the more I realized that the whole question of canceling books written by people who aren’t great is an important conversation to have. We wouldn’t be able to have that conversation without understanding what the work was.”

“We embrace discussing authors’ lives in the English department, and we always seek to do the ever-unfolding work of examining texts in multiple contexts,” Ms. Yurchak, Interim Chair of the English Department, wrote over email when asked to speak about the way the Upper School handles similar situations. “In my own classes in the Upper School just this year, we’ve struggled with the controversial legacies and perspectives of Margaret Atwood, Zora Neale Hurston, Alice Walker, and others. Literature is inevitably about human frailty, and it gives us opportunities to examine not only authors’ failings but our own as well. When we can provoke discussion by sharing biographical information as the Middle School Humanities team did, we believe we begin critical and powerful new avenues for thinking.”

![Dr. Zanita Kelly, Director of Lower and Middle School, pictured above, and the rest of Westridge Administration were instrumental to providing Westridge faculty and staff the support they needed after the Eaton fire. "[Teachers] are part of the community," said Dr. Kelly. "Just like our families and students."](https://westridgespyglass.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dr.-kellyyy-1-e1748143600809.png)

Hailey T • Mar 21, 2022 at 2:24 pm

super interesting piece! didn’t know this was happening in middle school but this article was really informative 🙂

Helena • Mar 21, 2022 at 1:11 pm

Such an insightful analysis of different perspectives! Great job.