Honoring the Past While Analyzing the Future: Reflections on Growing Up in a Post 9/11 World

One staffer reflects on growing up in a post 9/11 world.

My stomach twisted itself into knots when Joe Busch, Upper School Math teacher, told me about the grinding sound of the tower collapsing, watching it burn, and seeing people jump from the buildings. Here was someone who watched this horrifying event happen right before his eyes, and I, a person who wasn’t even alive on 9/11, was supposed to write an article about it.

We sat down in the garden outside the science building, right next to the street. Every few minutes a big truck or loud car would drive by, and Dr. Busch would smile or laugh about it even throughout telling his story. When he started to talk about that day, he began with a more informative and formal tone, telling me how his day started and where he was when the first tower was hit. But as his story went on, the tone shifted to become heavier and more serious.

Dr. Busch closed his eyes and flinched a little when talking about the sound of the towers. “The windows in our apartment were open, and we could still hear the tower collapse. It sounded a lot like a big earthquake, like a low rumble. It was so awful that I will never forget.”

“We went up on the roof to get some air, which wasn’t really a good idea because we could see the other tower burning,” he continued. “And…you could see people jumping.” He paused, taking a breath. His pain, like many others, was still there, even 20 years later.

Every year, we listen to stories about 9/11 and watch presentations and reflections about it, but admittedly it’s always felt distant to me and perhaps many of my peers who weren’t yet born. To me, 9/11 is history. To most adults, it’s memory. Although I feel a great deal of empathy when reading articles and hearing memories or stories from that day, 9/11 has never been something that has had a palpable emotional or personal significance for me. How was I supposed to interview someone about this raw and terrifying day when I was never there to experience it?

Adults always talk about the difference before and after 9/11. Often they will mention a loss of innocence. When I hear this, I wonder how BIPOC individuals feel when their experience has been one of decades of oppression and violence.

Other than Pearl Harbor, 9/11 is the only other time the United States has experienced an attack on American soil. The geography of the United States gives us a military advantage in that protected us from external acts of aggression. However, throughout history, the United States has been no stranger to acts of violence within our borders.

There is an important distinction to be made between acts of war and internal conflict, though our respective responses have differed. When I spoke with Sandy de Grijs, Upper School History teacher, she reminded me that the United States has been fighting a war on terror in Afghanistan for longer than I’ve been alive. “I used to do an activity in my classes that really made the students ask: How do you define who the terrorists are? Terrorism is political, and defining it always comes from a certain point of view. It becomes really tricky, and in my view, launching this global war on terror gave license to all these other groups to target people and justify it by saying that [the groups targeted] are terrorists.”

Violence seems to only beget more violence. In a post-9/11 America, people like me have grown up in a place the threat and fear surrounding terrorism, war, and domestic violence seem far more normalized. We have been exposed to school shootings and gun violence since we were in elementary school. Whatever innocence we may have previously enjoyed seems like a distant memory—or a fantasy depending on how old you are.

So too does a united America seem like a dream. I’ve been told that in the immediate months following 9/11, the nation came together in this shared moment of grief and resolve. And it wasn’t just the American citizens—support from the international community poured in as we rebuilt. It’s hard to imagine a united America when the current rhetoric is so divisive. But it feels like, after that initial solidarity, we returned to division and hate. Without taking any time to mourn, the US launched the war on terror and Islamophobic hate speech surged. “In retrospect, it’s a shame because there was all this goodwill all over the world at first… but even that goodwill was eventually squandered,” said Ms. de Grijs.

Being born in this generation is different. We are a generation that has only ever experienced the aftermath of 9/11: war, vulnerability, and hate. When a lot of people remember 9/11, they remember the loss. And given their proximity to the event, that makes sense. For me, 9/11 has always been a moment in history, but so much of the world around me bears the impact of that day, in ways I often take for granted. Dr. Busch reminded me to acknowledge the pain and loss many relive each anniversary, and Ms. de Grijs challenged me to consider the geopolitical and historical impact. It’s in balancing both views, the personal and the global, that we can honor the past and while still thinking critically about the present and future.

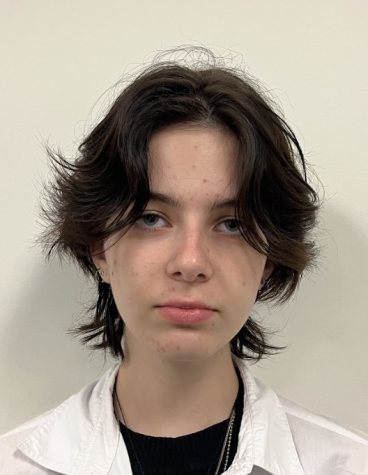

Daria is a senior in her fourth year on Spyglass and third year as an editor. Outside of Spyglass, you can find her reading (typically about quantum physics),...

Addie is a senior, and has been illustrating for Spyglass Design since 8th grade. In their free time they enjoy sewing, painting, and watching campy horror...

![Dr. Zanita Kelly, Director of Lower and Middle School, pictured above, and the rest of Westridge Administration were instrumental to providing Westridge faculty and staff the support they needed after the Eaton fire. "[Teachers] are part of the community," said Dr. Kelly. "Just like our families and students."](https://westridgespyglass.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dr.-kellyyy-1-e1748143600809.png)