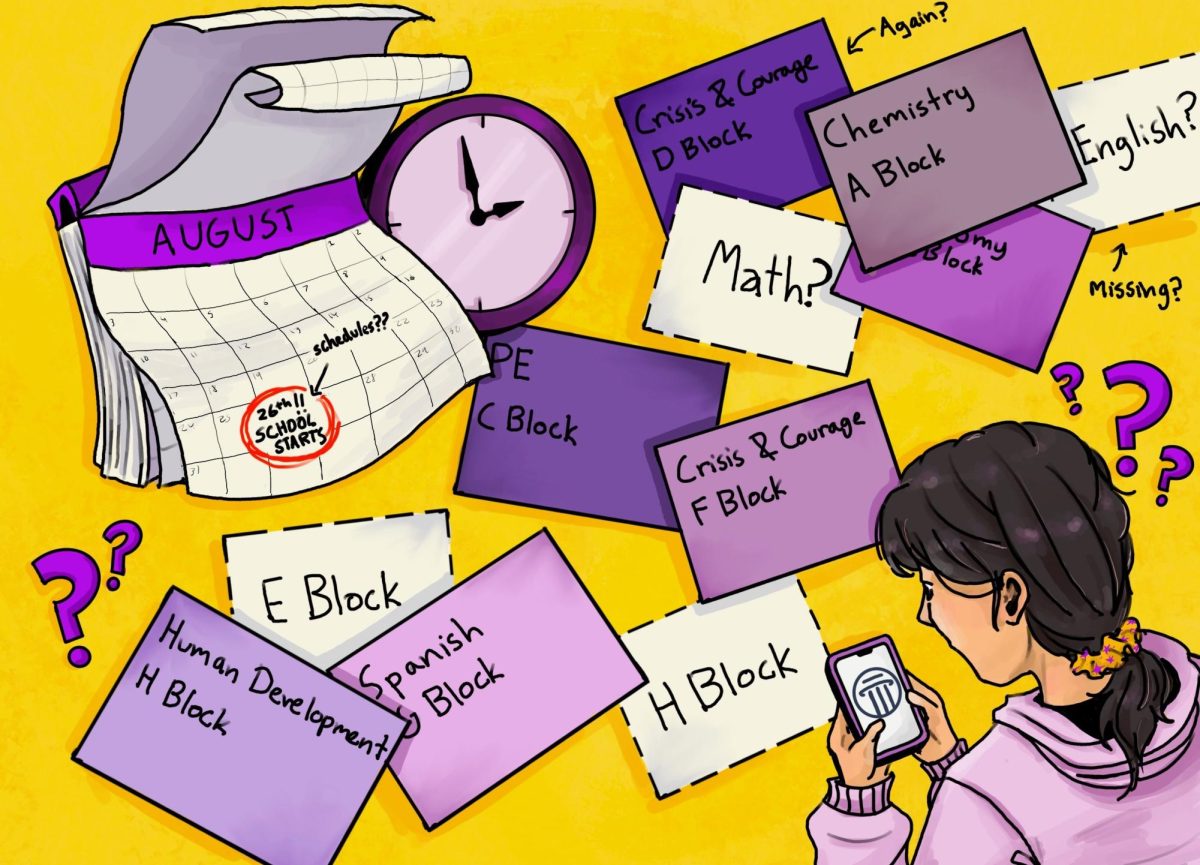

Every August, about two weeks before the school year starts, students anxiously log onto Veracross to check their new schedules. Students frantically text each other, “Which teacher did you get?” and “Should I try to switch classes?”

While they may be disappointed about having different schedules than their friends, students are often more concerned about which teacher they have been assigned, particularly when the same class is taught by multiple teachers.

At Westridge, this is especially common in freshmen and sophomore year, when almost all students take the same classes, specifically in English, History, and Science. Some variation between classes is expected—no two teachers will ever be identical—but the differences between class policies, expectations, grading standards, and sometimes class resources and content can vary significantly.

Katherine D. ’28, a freshman who has been at Westridge since the 4th grade, said having multiple teachers for a class is “something I’m not used to yet. In 8th grade I could talk about the classes more with my friends. Now we can’t really because [they’re different].”

When asked about different assignments for her English I class, Charlotte H. ’28 said, “In [another teacher’s class] they’re writing sonnets and stuff. We never wrote sonnets in my class. We’re just writing papers.”

Amelia H. ’28 noticed that in her English class, instructional assignments vary. “We’re working on small paragraphs and grammar while other classes are done with their essays already,” she said. “Not saying it’s bad or anything, but the grading systems are also different and so it feels like a different expectation for every class.”

Another ninth grader felt the instructions given by her friend’s History teacher were more specific, while her teacher had her “just do it” and gave specificity in their feedback afterwards. Similarly, Giselle R. ’28 said, “The teachers are very different—their teaching styles are different, the grading styles are different. Just everything we learn is…different.”

With the varying assignments, teaching styles, and assessment practices—class participation, in-class writing, take-home essays, etc.—it’s not uncommon for some students to feel at a disadvantage. Isla R. ’25 said, “It feels really unfair, because it might be easier [for me] to do better in another [teacher’s] class.”

Different departments try to balance teacher autonomy and the need for consistency, structuring a class with a lockstep approach.

The English Department

In each English class, teachers structure the year around the same selection of books, though they may be assigned in different orders. Last year, English I—a required class for all freshmen—was taught by Mr. Max Duncan and Mr. Ed Raines, who each began the year differently. Mr. Raines dove into the canonical The Odyssey as the first book of the year, and Mr. Duncan began with Sandra Cisneros’s The House on Mango Street, a book that, with over 300 fewer pages, he believes serves as a “touchstone” for students just beginning their high school journey.

This year, English I is taught by four different teachers, as opposed to just two or three in previous years. Over the summer, the English teachers met to restructure the English I curriculum. Mr. Duncan said, “Every teacher wants you to have the similar experiences and the same outcomes. So I think that that was one thing that we looked at.”

The English Department also added in a “Writing Workshop” to the beginning of the year for all 9th graders. The Writing Workshop portion of English I class spans the full first quarter and consists of reading different short texts—with each teacher choosing from a pool of agreed-upon works—and writing an analytical paragraph about each text. This process was repeated a few times for each English I class, giving students adequate time to reflect on the writing process, visit the Writing Center, and meet with their teachers.

The addition of the Writing Workshop was made in the hopes of helping students with different English class experiences and writing levels align with standardized expectations. “With alignment, it’s not necessarily that every class is exactly the same, but with being able to meet the needs of students to have the common experience we have made some new changes,” said Mr. Duncan.

While all English teachers provide written feedback, only some teachers will choose to include a grade range that the work falls under, and individual rewrite policies vary.

The History Department

The freshman required History class, “World Views: Connections Between the Ancient and Modern,” has been taught by only two teachers for the past few years. In addition, the teachers use the same textbook and the “History Writing Guide,” an in-depth guide made by Ms. Jennifer Cutler to inform freshman History students of Westridge History writing norms.

In 9th grade History, Mr. Bill Harrison and Ms. Cutler assign roughly the same amount of papers. However, essay prompts and requirements as well as the time spent on each unit can vary.

Meanwhile, in 10th grade History, where students have a choice between regular History and a more difficult Challenge by Choice add-on, the teachers use the same materials and assignments. The three teachers of Crisis and Courage in Global History, History Department Chair Ms. Melissa Kelley, Ms. Jennifer Cutler, and Ms. Sandy de Grijs, have compiled a unique “pacquette” for each of the units, leaving students with a neon-colored packet of primary and secondary sources to guide their history journeys.

Understandably, class lectures and discussions still vary, but students appreciate having the same assignments in sophomore year. “I feel like [the classes] are more universal this year,” said Miyari V. ’27. “There’s more of an effort [sophomore] year being made to make the classes [taught by different teachers] more similar,” echoed Willow S. ’27.

The Science Department

Science classes are rarely taught by multiple teachers, but in the case of Biology I, a required class for ninth graders, Ms. Laura Hatchman and Ms. Brooke Surin choose to teach in a lockstep approach. In lockstep learning, teachers move at the exact same pace with the same assignments, making an effort to reach all course milestones at the same time.

“[It’s] definitely one of the intentions of keeping it the same, so that every single ninth grader gets the exact same experience in Biology,” Ms. Hatchman said.

According to Ms. Hatchman, her approach to working with Ms. Surin is, “We’re different people, so we might deliver the material in different ways, but you’re having the same platform, [OneNote,] and the same assignments, and the timing and pacing is the same,” she said. “We hope that that creates equality, and fairness, and all those things.”

Ms. Hatchman believes her class is easier to teach in lockstep. One of the reasons the lockstep approach might work in Science classes as opposed to humanities courses is that many Science courses require a firm understanding of a concept—not an individual interpretation that can be graded subjectively. Ms. Hatchman also integrates multiple ways of teaching and evaluation to support all styles of learning, including projects, group worksheets, labs, and more.

Additionally, Biology I classes are intentionally structured with extra time, which acts flexibly if a class needs more time or if a teacher needs to work individually with a student. While small changes may be made from year to year, the class is also designed with the understanding that students may have limited experience in biology if they are new to Westridge.

The lockstep approach has been effective in Biology even though Ms. Hatchman has had different teaching partners over the years. “Lockstep works well for biology because the testing is more similar for each class, and I can collaborate with students in other classes,” Shania W. ’27 said.

Teacher Autonomy

Despite the success of the lockstep approach in Biology, it may not be the right fit for all classes, especially humanities subjects. “Especially for History, you want teachers to play to their own strengths and individuality. You want people to be able to show their passion in the classroom because students really respond to that,” Ms. Kelley said.

“Part of what makes Westridge so great is not only that we have this autonomy, but we get to do what works. If someone were to hand me a curriculum and say, ‘do it this way,’ I don’t have ownership over that. I’m not going to do it as well as whoever made the curriculum,” Ms. Cutler said.

As an independent school, Westridge is in a unique position to allow teachers and curricula more flexibility, as demonstrated by the recent shift away from APs. Alongside “promoting deeper and more relevant learning,” according to an email from former Head of School Ms. Elizabeth McGregor, the new courses provide teachers with new opportunities as they gain a sense of ownership over the classes.

Mr. James Evans, Director of Teaching and Learning, said, “We trust in the autonomy of teachers and in the understanding that they’re working to deliver the mission with excellence, whether that’s in terms of the school mission or the department mission.” He also noted that within departments, teachers will check in with each other to compare grading, workload, and their current progression in the course.

Moving Forward

It is inevitable that students’ experiences will vary. Not every teaching style will suit every student, and one student’s challenge might be another’s cakewalk. Ultimately, at the end of a student’s Westridge education, the hope is that they leave with the same knowledge and skills as others in their grade.

“In a school like ours, we have lots of systems in place for input and for feedback. We want to make sure that all roads lead to progress and growth for students,” Director of Upper School Dr. Melanie Arias said. For many students, this hope ultimately becomes a reality.

Recent Westridge graduate Julia Hughes ’24, said, “Everything that you need to succeed, any Westridge teacher will allow that to happen.” She added, “I do agree that…every teacher is different…But at the end of the day, any class at Westridge that you take can get you where you want to go.”

Correction (10:38 a.m. Nov. 18):

– A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that only two faculty members teach 10th-grade history. In fact, three teachers instruct 10th-grade history courses: Ms. Sandy de Grijs, Ms. Jennifer Cutler, and Ms. Melissa Kelley. The article has been updated to reflect this.

![Dr. Zanita Kelly, Director of Lower and Middle School, pictured above, and the rest of Westridge Administration were instrumental to providing Westridge faculty and staff the support they needed after the Eaton fire. "[Teachers] are part of the community," said Dr. Kelly. "Just like our families and students."](https://westridgespyglass.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dr.-kellyyy-1-e1748143600809.png)