This article is a follow-up to the article titled “How Does Westridge’s Culture of Competition and Achievement Impact Eating Disorders?” by Katie S. ’23.

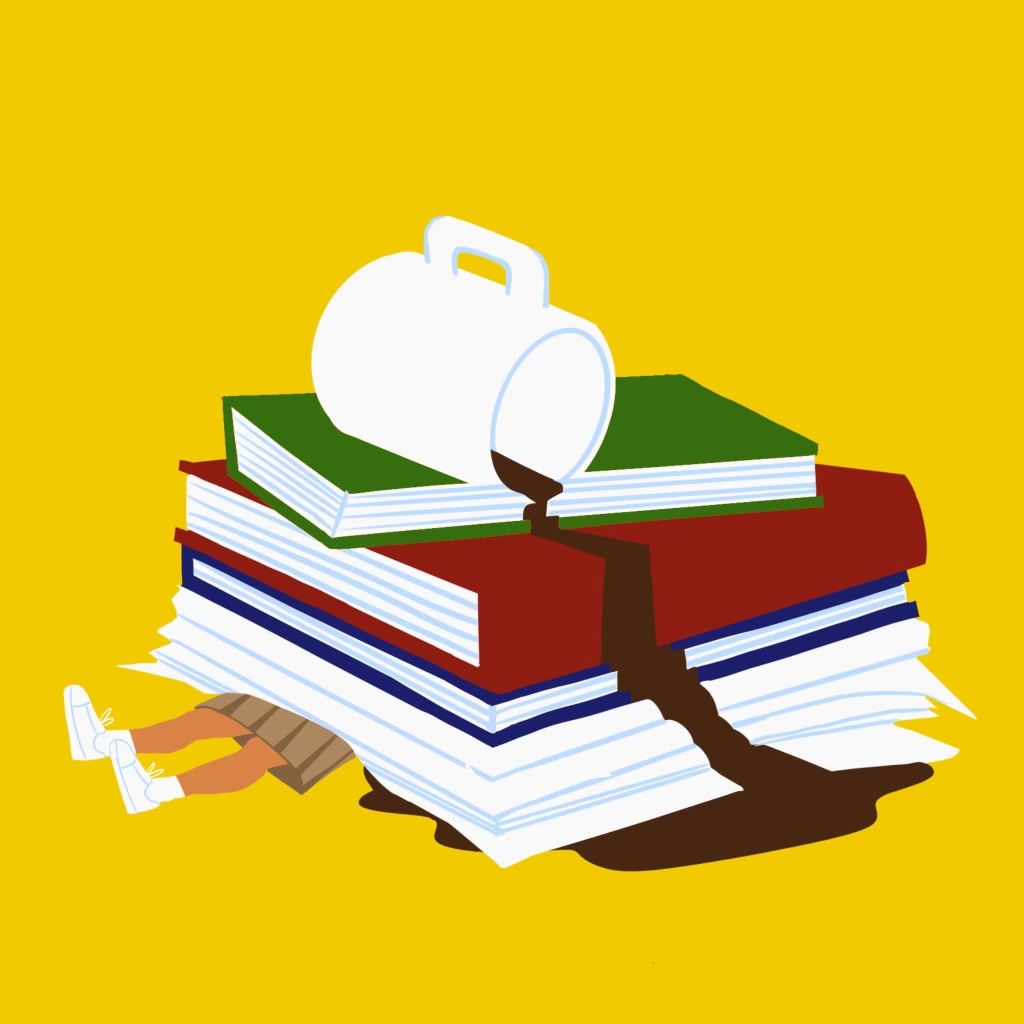

It’s 3:10 p.m., and the sum total of my nutritional intake for the day is a few slurps of coffee, one bite of a protein bar, and the oceans—one refillable bottle at a time—of water that I drink in an effort to keep my stomach from growling disruptively in class. I am not intentionally cutting calories. I am simply following the official Westridge diet, which requires students to subsist on activities and responsibilities instead of food.

At Westridge, the block of time labeled “Lunch” on our schedule is used for everything BUT eating; indeed, “lunchtime” is synonymous with “free block” in terms of expectations around student availability. The use of the midday meal time as a repository for academic and extracurricular overflow is deeply ingrained in Westridge culture and practice. Lunchtime is when students meet with teachers, take make-up tests, utilize the Writing and Math Centers, and participate in affinity, club, and service rep meetings and activities. It’s when students with accommodations for learning differences get extra time on in-class assessments. Students are expected to eat around the edges of these activities—never mind that the Commons lines are too long to make a quick bite possible or that it’s hard to choke down an entire brown bag lunch in a few minutes when one is madly preparing for whatever is coming next. Even HAP (“History and Pizza”), is not much of an opportunity for nutritional intake when one is focusing on participating in a meaningful and possibly impressive manner to earn CBC credit.

Given the fraught relationship many students at Westridge have with food and healthy patterns of eating, it behooves the school to hold space during the academic day for the nourishment of body and soul that a lunch period dedicated to eating and social connection provides. Instead, our use of lunch as a catch-all/catch-up time demonstrates a troubling institutional disregard for the importance of eating. This year, with Upper School lunch starting at 1:10pm, just before the last block of the school day, mealtime feels more like an afterthought than ever.

If the degree of risk for eating disorders on campuses were measured like wildfire danger, Westridge would be on perpetual “extreme hazard” red alert. As Katie S. ’23 noted in an article on this topic in Spyglass’s last edition, certain realities are “baked into” the landscape at elite girls’ schools like Westridge. Adolescent girls are twice as likely as boys to struggle with an eating disorder, and high academic achievers at schools with “aspirational cultures” are at higher risk for eating disorders.

Katie’s article (“How Does Westridge’s Culture of Competition and Achievement Impact Eating Disorders?”) explored the ways in which the culture of competition and the competitive nature of students at Westridge and other academically rigorous schools contribute to the disturbing prevalence of eating disorders. Student interviews revealed that some can feel overwhelmed or outmatched academically and struggle with self-worth in Westridge’s competitive environment; because these students feel out of control with coursework, they seek a sense of mastery by exerting control over their food intake and weight. Westridge also tends to attract high achievers who are competitive by nature. Some of these students satisfy their drive to succeed by trying to “win” the competition to be thin.

Both Westridge students and administrators readily acknowledge that school culture can exacerbate disordered eating. We have Human Development (HD) class curriculum around eating disorders, Peer to Peer resources, and Everybody for Every Body Week—a whole week dedicated to promoting body acceptance—in place to combat pervasive disordered eating, unhealthy relationships with food, and poor body image among students. We dutifully discuss the need for downtime, mindfulness, self-care, and boundary-setting in advisory, assemblies, and HD.

But actions speak louder than words, and if the school is serious about promoting healthy eating and student wellbeing, the practice of cramming lunchtime full of activities must stop.

On a basic level, the “Westridge diet” normalizes skipping meals and facilitates the deceptive practices that kids struggling with EDs employ. It would be almost impossible to discern whether a student needs help with disordered eating or is simply an active and engaged member of the Westridge community (which means you never eat at lunch). For students recovering from EDs, sticking to scheduled eating programs can be difficult; it’s much easier to yield to the temptation not to eat.

More subtly, though, Westridge sends the message that eating is not a top priority by scheduling “official school business” at lunchtime. When students complain about not having time to eat during lunch, I have heard teachers suggest that students eat bigger breakfasts, eat during free blocks, or grab a protein bar during passing periods. These well-intentioned workarounds for normal consumption offered by authority figures shape our perspectives on food and eating; students are internalizing that we should be able to push through being hungry and that we should not need downtime to socialize and ingest food in a calm and unhurried way.

Dr. Lisa LaFave, Director of Counseling and Student Support, observes that although Westridge works hard to “encourage girls to take up the space in the world,” disordered eating is often part of a person’s struggle with prioritizing their own needs. When considering Westridge students’ frenetic participation in lunchtime activities, Dr. LaFave notes, “Unfortunately, you’ve got a culture that has a lot to say about women and their bodies and food and intake. . . I think it invites students to mindlessly continue to churn out and perform and not be reflective about what they actually need.”

Indeed, as a community, we are so steeped in the go-go-go pace of the Westridge school day that it is hard to imagine setting boundaries and protecting the lunchtime space. Undoubtedly, many of us would be beset with FOMO, or worry that by not participating in lunchtime activities we were falling behind our peers in the race to “do it all.” Moreover, in the current environment, refusing to make oneself available during lunch would likely be viewed as outrageous, diva-like behavior by both faculty and other students.

Like other unhealthy habits that nobody wants to give up, the Westridge diet (high activity, low food) is probably here to stay, at least in the near term. However, Dr. LaFave offered a summation of the problem, solution, and hope for the future that we should all work toward: “[T]here are so many messages that you should give to your own depletion, and that you should quiet your voice and fit in. And I just think it would be countercultural and amazing for us to say, ‘No. Lunchtime is off-limits. This is my time, we’re going to have to figure something else out.’” I’m with her!

![Dr. Zanita Kelly, Director of Lower and Middle School, pictured above, and the rest of Westridge Administration were instrumental to providing Westridge faculty and staff the support they needed after the Eaton fire. "[Teachers] are part of the community," said Dr. Kelly. "Just like our families and students."](https://westridgespyglass.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dr.-kellyyy-1-e1748143600809.png)