Westridge Raises Questions About the Future of Artificial Intelligence in Education

After the emergence of ChatGPT, students and faculty at Westridge are having conversations about AI’s potential impacts on academics.

In an Upper School AP Computer Science Principles class, Holly N. ’25 sits in front of her computer and watches curiously as a ChatGPT look alike comprehensively responds to her prompts regarding topics ranging from the Russian Civil War to YouTube drama between make-up artists Tati Westbrook and James Charles. The strong accuracy and concise writing style leaves Holly surprised and unsettled.

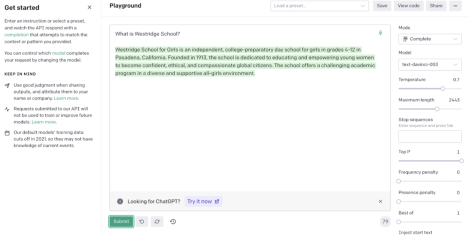

Launched in November 2022, ChatGPT is powered by artificial intelligence to generate human-like responses when prompted by a user. Its capabilities include writing code, translating texts, writing essays, and even constructing news articles. Because of its accessibility, some students have been taking advantage of the resource and using it to help them in their coursework.

“AI technology really shocked me when I saw how far technology has come. It was amazing to see AI write about anything and everything just at the touch of a button. It took me aback how AI could write about even the most obscure topics with great detail,” said Holly.

The exploration of AI and its capabilities is a part of a project assigned by Westridge Computer Science and Robotics teacher, Autumn Rogers. Rogers said that she wanted her students to better understand the power of AI and how it will make an impact on technology and learning. “The reason I wanted to introduce people to it is because it’s a really incredibly valuable tool that I think could be really beneficial to use in your life.” Rogers introduced AI into her curriculum because of the increasing discussions regarding ChatGPT in the teaching community.

The introduction of ChatGPT into an already cheating-saturated educational system has heightened the fears and worries of many academic institutions. Gabriel Rossman, a professor of Sociology at UCLA told The Free Press that students who use AI are “immoral.”

However, according to Ms. Sandy de Grijs, an Upper School History teacher at Westridge, it comes down to students and the choices they’re going to make about their learning. Ms. de Grijs does not believe her students would outright cheat. “So this would mean a kid would literally have to decide to cheat. I just haven’t seen that a lot at Westridge, where kids do that,” she said.

An unnamed senior said she questioned the ethics of using ChatGPT: “You could ask [ChatGPT] to write one sentence of an essay, or you could ask it to write your whole essay—which I think is very dangerous. So as of now, I don’t think there is a way to use it correctly or ethically.”

She continued, “Maybe in the future, there will be schools that will adapt it to have certain limitations, which I think could be very helpful. But for what ChatGPT is right now, I don’t see it that way.”

Because of artificial intelligence’s recent rise, many teachers and administrators have been having conversations about its role in education. Back in January, the Upper School division met to talk about the rise of ChatGPT in education. The reactions to artificial intelligence’s emergence are mixed.

When English teacher Ms. Anna Oseran first learned about ChatGPT, she found herself going down a rabbit hole. She described her reaction as “fascinated, intrigued, shocked, [and] horrified.” Her reaction—like many other concerned skeptics—is understandable, given AI’s incredible aptitude. In January, ChatGPT was able to successfully pass an MBA exam administered by a professor at the Wharton School of Business.

Dr. Christian Terwiesch, a professor at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania administered the research about ChatGPT in which ChatGPT3 (a version of the artificial intelligence) was able to pass the final exam of the school’s Master of Business Administration program. Terwiesch said the ChatGPT3’s written responses earned itself between a B- and B on the exam. He said about his findings: “[ChatGPT3] has important implications for business school education, including the need for exam policies, curriculum design focusing on collaboration between human and AI, opportunities to simulate real world decision making processes, the need to teach creative problem solving, improved teaching productivity, and more.”

Ms. Oseran acknowledged that while AI may have some great applications, she was concerned about AI and its impact on students’ critical thinking skills. “I think, morally, in an English class and at a school where you’re trying to teach kids to develop critical thinking skills, by the mere fact of using ChatGPT, [students are] not learning critical thinking,” said Ms. Oseran.

Ms. de Grijs has worked at Westridge for over 25 years and has seen how technology has impacted teaching and learning. Like Ms. Oseran, Ms. de Grijs and the rest of her department have experimented with ChatGPT. Ms. de Grijs said that she is in “wait-and-see mode” but also “weirdly not concerned.” She attributed those feelings to her trust in her students but also from her experience as a teacher.

While concerns over academic integrity and student learning are not insignificant, several teachers at Westridge are optimistic about the positive possibilities of AI and its impact on education. Middle and Upper School Rocketry teacher Mr. Daniel Perahya was one of the first Westridge teachers to speak out about AI. In an Upper School faculty meeting, he recalled that calculators were once thought to be detrimental to a student’s learning because they would eliminate utilizing mental math. Of course now, in spite of the previous apprehension, calculators are incorporated into math classes on a daily basis.

“[AI] is here to stay. It’s a tool and we need to learn how to use it—not run away from it,” said Perahya.

Mr. Gary Baldwin, Director of Upper School, thought similarly to Mr. Daniel Perahya. He said, “I think that again, when the internet came along, teachers lamented the depth of research skills, kids won’t know how to use a card catalog, they will not know how to use a library, and they don’t know the Dewey Decimal System. Turns out that was okay.”

Teachers in the science and math departments are not the only ones who are ready to embrace AI.

Despite her initial concerns, Ms. Anna Oseran still believes that there is potential to incorporate AI into education. “I think over time, we’ve sort of realized, this might not be as big of a problem as we initially thought it was,” said Ms. Oseran.

Still unsure of the possibilities of AI in education, Ms. Oseran said she is open to incorporating it as a tool in the English curriculum. “I think if there was a way to figure out a way to embrace it or adapt it in some way, that’s something that we’re open to,” said Ms. Oseran.

Mr. Baldwin is unsure about how AI could be incorporated in academics, but he knows there will likely be change. “Research just changed. And so ChatGPT is going to change things for sure. But we don’t know yet. We will continue about the business of educating kids,” said Mr. Baldwin.

Mr. James Evans, Director of Teaching and Learning, believes that ChatGPT can be integrated into learning when the situation is suitable. He also sees the emergence of ChatGPT as an opportunity to reflect on learning in general. “I think it’s a really good opportunity to explore the philosophical constructs behind what learning is, but also the ethical aspect of it is kind of fascinating as well,” he said.

Students at Westridge have mixed feelings about the ways in which ChatGPT can be utilized or become a resource in their classes.

Alice C. ’25 expressed her fear of using ChatGPT: “The little I know about it completely fascinates and scares me. I think it could be a super-cool resource, but I don’t know a ton about it and am too skeptical to try it out.”

Audrey B. ’25 said, “The goal of school is to learn. But it’s like, I feel like [ChatGPT] more strips away from learning then accelerates it. A lot of people said similar things with the internet: if you abuse its power, then you abuse its power. If you use it as a good resource, that can accelerate your learning. You can totally just cheat on homework on the internet, but some people don’t do that. So it’s just the same mindset for utilizing the internet as it is on ChatGPT.”

Julia W. ’24 said, “I feel like in some ways, [ChatGPT] can be helpful, because I know that some people use it for math.”

Whether students and faculty are eager to incorporate AI into their teaching and learning, like many of them have acknowledged, AI is likely here to stay. Ms. Autumn Rogers said, “If we don’t adapt to [AI] and try to incorporate it, then I could imagine there being some very significant learning loss. I hope learning and teaching styles will change—I feel like they have to, in order to ensure students are still learning.”

Ella is a senior and the Editor-in-Chief of Spyglass, now in her sixth year on staff; in the three years prior, Ella has served as Social Media Manager....

Tanvi is a senior, in her fourth year as a writer, and her first year as Managing Editor for Spyglass. In her free time, you can find her listening to...

Lauren Cho is a junior Spyglass Design artist. She has spent the last two years as a staff writer, but she wanted to join the Design Team this year to...

Ilena is passionate about stories— especially histories— good snacks, and bad puns. She has been on Spyglass for a very long time. Ilena is a senior.

Ilena is passionate about stories— especially histories— good snacks, and bad puns. She has been on Spyglass for a very long time. Ilena is a senior.

Gia is a senior in her fourth year as a Spyglass staff writer and third year as a Copy Editor. She loves solving crossword puzzles and crocheting little...

Sabina is a junior and returns to Spyglass from her year long hiatus. She enjoys the opportunities spyglass gives her to connect and interact with the...

Valentina is a senior in her fourth year of writing for Spyglass. Valentina loves American Girl Dolls, theatre, and her amazingly supportive family. She...

Lilah is a senior and a fourth year Spyglass staff writer. You can find her watching movies with her friends, shopping at thrift stores, and searching...

![Dr. Zanita Kelly, Director of Lower and Middle School, pictured above, and the rest of Westridge Administration were instrumental to providing Westridge faculty and staff the support they needed after the Eaton fire. "[Teachers] are part of the community," said Dr. Kelly. "Just like our families and students."](https://westridgespyglass.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dr.-kellyyy-1-e1748143600809.png)