“What does it mean to be a girls’ school when we’re no longer living in a binary world?”

“What does it mean to be a girls’ school when we’re no longer living in a binary world?”

“What does it mean to be a girls’ school when we’re no longer living in a binary world?”

Ms. Sarah Jallo, Senior Director for Enrollment Management and Student Outcomes, explained that this is a “big question” for Westridge’s administration. Over the past seven years, this question has become a national conversation involving other girls’ schools and single-gender organizations, including the Boy Scouts and Girls on the Run—all wondering how to stay true to their missions while remaining inclusive and relevant in an increasingly non-binary world.

At Westridge, the question often boils down to striking a balance between Westridge’s explicit mission as a girls’ school and its implicit mission of supporting individual students. This balancing act considers everything from how student pronouns should be approached (refer to everyone as “girls” and “ladies” or opt for the general “students”?) to how far the girls’ school mission should reach, how policies should be crafted, and how students can be best supported through it all.

The Retention and Admission Policies

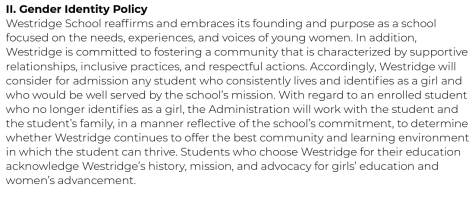

Many of the students interviewed who don’t identify as female explained that they identified as female when they first applied to Westridge, but they later came out while attending Westridge. When these students came out, they knew they wouldn’t be forced to attend a different school because of Westridge’s Gender Identity Policy. It states, “Westridge does not intend for any student to be denied continued enrollment based on a change in gender identity and asserts that there is no inherent reason to question the continued enrollment of any trans student in good standing.”

The policy adds, “We do recognize, however, that it is not uncommon to find that when students become open about their identity, they feel a co-ed school might be a better fit. In that case, we will work with the family to help them find the school that provides the best fit for the student.”

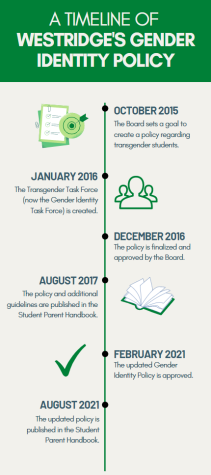

The creation of the Gender Identity Policy, originally called the Transgender Policy, was a multi-year process that began in October of 2015 when the School Committee of the Board set a goal to create the first policy addressing transgender students. A few months later, in January of 2016, the Transgender Task Force, since renamed the Gender Identity Task Force, was assembled. It consisted of faculty, staff, members of the administration, students, parents, and the Board.

Less than a year later, in December of 2016, the new policy was finalized by the Gender Identity Task Force and approved by the Board, later published in the Student-Parent Handbook for the 2017-2018 school year. It stated, “With regard to an enrolled student who no longer identifies as a girl, the Administration will work with the student and the student’s family to address continued enrollment, taking into account the best interests of the student and the school community.”

Ms. Jallo put it succinctly. “If you want to stay, and this still feels like your community, then you can stay.”

So what does it mean to be a girls’ school when the student body isn’t exclusively female-identifying?

Dr. Zanita Kelly, Director of Lower and Middle School, explained, “Our outward-facing identity is a girls’ school. We are here for girls. If that changes while you are in attendance, you are welcome because that is what women do. We are accommodating, and we are welcoming. You are welcome to be here no matter how you identify once you’re here.”

Dr. Margaret Shoemaker, Director of Admission, explained the aspect of Westridge that is intent on empowering girls and how that fits in with the fact that several students do not identify as girls. “We are empowering students who don’t identify as male. If they do start to identify as male when they’re here, they are charting their own path of empowerment, and they got there here.”

Mr. Gary Baldwin, Director of Upper School, said, “These are our students, and wherever they are on their individual journeys we’re going to support them. It’s that simple.”

He added, “Our support for the individual students does not mean our mission isn’t what we say it is.”

After the Transgender Policy was created and published, the Westridge administration recognized that they had answered the question of retention and who gets to stay at Westridge, but the question of admission remained: What about students who aren’t biologically female but are interested in Westridge?

In October of 2019, after an annual review of Westridge’s policies and progress as a school, the task force began a conversation to address the question of admission. Ms. Jallo, who played a large role in crafting the policy, explained that she collected general data from other secular girls’ schools to guide the administration and Board in updating the Transgender Policy. Of the 60 secular girls’ schools in the United States and Canada that are members of the National Association of Independent Schools, Ms. Jallo collected data on 29. She found that 23 have admission and retention practices similar to Westridge’s, five have no policies around gender identity, and one has a policy stating that only biological girls can apply.

The Board approved Westridge’s updated policy in February of 2021 when both questions of admission and retention were addressed. At the start of the 2021-2022 school year, the Gender Identity Policy was placed and published in the Student-Parent Handbook. The added information about admission states, “Westridge will consider for admission any student who consistently lives and identifies as a girl and who would be well served by the school’s mission.”

Though the Gender Identity Policy has been updated, Ms. Jallo explained that this isn’t the end of the work. “It’s not this issue of ‘Okay, we’re done with that and now we have a policy, work is done!’—it’s really like this is where we are as a school today, this fits in with where we are as a society, but who knows?”

Some women’s colleges, like Mount Holyoke, have announced that any student who isn’t a cisgender man may be admitted to their school, not just students who identify as female. Ms. Jallo explained, “We’re not there as a girls’ school yet. Will we be? I don’t know. We’re going to have to see where our culture takes us. We feel strongly today that our identity is as a girls’ school, so we feel we’re in the right place right now with this policy, but it is a constant review and evolution.”

Dr. Kelly explained, “I think that if we are going to remain relevant, then we are going to have to consider what these definitions of the female and of women are. If we don’t grow [as an institution], if we don’t evolve, then we die. In order for us to continue to thrive, I believe those things will have to evolve and change, too.”

“Girls” or “Students”?

Westridge’s Gender Identity Policy Additional Guidelines states, “Westridge will preserve its identity as a girls’ school. As is currently the practice, female pronouns and references will be used in formal settings and publications, and as a regular and accepted part of the School culture.”

In classrooms and smaller groups, “The School will strive to support a student’s preference regarding name and pronoun use.”

Several students who don’t identify as female explained that they feel uncomfortable at assemblies and large school gatherings when speakers and faculty address the mass as “girls” or “ladies.” Alex S. ’24, who identifies as non-binary and uses they/them pronouns, said, “I think mostly just this feeling of impostorism that comes from it because in assemblies people are like, ‘Oh welcome girls.’”

Rowan*, an Upper School student, who identifies as nonbinary, said, “There are situations where they could say ‘students’ instead of ‘girls,’ and stuff that would’ve made a big difference to me.”

Mr. Baldwin said, “This is where the broader mission of the school operates in a way that’s not totally clear with the other mission of supporting the individual kids. Are there times when you can easily avoid a gendered pronoun when you are explaining? Then sure, when you’re talking to an audience of people that is not all of one gender, then you don’t need to use gendered pronouns.”

Dr. Kelly looks to Westridge’s core values to inform these situations. “We want to make sure we are accommodating and that we are doing everything we can to ensure the inclusion, respect, integrity—the core values have to remain the same. If that means that we have to adjust when we are talking to a group of students in an assembly, and we need to adjust our language so it’s non-binary, we can do that, absolutely. Because how much does that cost for us to be respectful and inclusive in our language?”

Some even wonder whether Westridge’s developing identity as a girls’ school necessitates the phrase “for girls” in the title “Westridge School for Girls.” Ms. Katie Wei, Upper School English teacher, explained, “I’ve been thinking about whether or not we want to change the name of the school to be ‘Westridge School,’ not necessarily to deviate from our mission, but just to take out the ‘for girls,’ and we can remain a school that is intent upon educating women and people who identify as female, but maybe we don’t need to have it in our name anymore.”

Ms. Wei explained that she defers to using “they” in reference to all students. “Many of us do because we’re all trying to be very mindful of just honoring who people are, and then I recognize on the flip side, I’m not honoring people who would prefer ‘she.’” The choice helps to avoid leaving out students who don’t identify as female, but she recognizes there are “implications on the other side.”

Ms. Jallo explained, “We acknowledge this is the school we’ve chosen to work at or to go to school, and it is a girls’ school, at least in our founding and our mission, so it’s hard to reconcile the mission with the individual—the collective and the individual.”

Support in Exploring Identity

Many students shared that they’ve been supported by Westridge’s community in their exploration of gender identity.

When Alex first came to Westridge, they were not out to others or themself yet. Westridge’s community helped Alex in discovering themself. It helped them to see “people who are older than me talking about their experiences, and people just being like ‘Yeah, that’s awesome.’ And teachers using ‘Mx.’ instead of ‘Ms.’ or ‘Mr.’ And just this complete acceptance of it.”

Kaya I. ’24, who identifies along the lines of agender and gender fluid and uses all pronouns, similarly explored their identity during their time at Westridge, specifically over quarantine. When Kaya came to school from remote learning, they still felt belonging at Westridge. “Nothing about Westridge really thrusts the idea of ‘girl’ at you—they don’t throw being a girl at you—so it doesn’t feel like I’m being forced to be something that I’m not, or like feeling uncomfortable for not being a girl,” they said.

Z G. ’22, Gender Affinity Head who identifies as transmasculine and uses he/they/it pronouns, experienced Westridge as a welcoming and accepting place. “I do believe that Westridge is a very supportive community. Everyone respects your pronouns or tries their best to put into practice the pronouns you share with them. Westridge is a very respectful place when it comes to it.”

Z has found a support system at Westridge through friends and affinities. Gender Affinity especially helped him in discovering his identity. “I think it’s really great of Westridge allowing that safe community, Gender Affinity and Skittles for people to discuss and learn and also be able to openly share with some students with the same experience.”

Alex also found a sense of community at Westridge, helping them to feel comfortable being themself. “I’ve found my little queer community, and I’ve made friends with upperclassmen and lowerclassmen.”

They added, “I’ve found my place with my people.”

*This name has been changed to protect the anonymity of the source, in accordance with Spyglass’s Anonymous Source editorial policy.

Katie is a senior, and this is her fifth year on Spyglass and third year as an Editor. In her free time, she loves playing guitar, writing, and doing calligraphy.

![Dr. Zanita Kelly, Director of Lower and Middle School, pictured above, and the rest of Westridge Administration were instrumental to providing Westridge faculty and staff the support they needed after the Eaton fire. "[Teachers] are part of the community," said Dr. Kelly. "Just like our families and students."](https://westridgespyglass.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dr.-kellyyy-1-e1748143600809.png)