May is Brain Tumor Awareness Month, and One Survivor Shares Her Story

Before I start, I begin with gratitude for those who hold a space for me to share my story. So, here it goes: I’m Nitya Chawla, and I’m proud to say that I am a three-time brain tumor (craniopharyngioma) survivor.

It started when I was seven and when I called Bandra, Mumbai my home. I went to and from school each day, complaining of terrible headaches, which everyone believed was just an excuse to leave class. But then I stopped growing. I complained to my parents, yet nobody heard me — until one day, my doctor noticed my symptoms. He told my parents that something was wrong, and it wasn’t just the short-statured genes my parents passed on to me.

During the next three years, from the time I was seven until I was 10 years old, I underwent three brain surgeries and a round of proton beam radiation therapy. My family and I moved to Los Angeles where I would receive ongoing care. That is my story and my history. I wish I could say that resecting my tumor pieced together my body, mind and old life. But it didn’t. And I live with that truth everyday.

Instead, I’ve had to learn to let some things go. I couldn’t play on the soccer team in third grade; I brushed it off. I got bullied. Kids called me pregnant, fat face; I brushed that off, too. But more than anything else, as a seven year old, I ignored the bubble of survivor’s grief that enclosed around me.

Grief that I spoke like a forty-year-old when I was eight years old.

Grief that I didn’t try to accept my difficult body sooner.

But mostly, grief that I did not allow myself to grieve what I had lost.

Instead, I coped by pushing myself harder than ever.

I lost my physical body, home, friends in India and sense of self in one month, but I was expected to bounce back like I always have because, well, apparently survivors are some kind of “superhuman” breed. This is a reality only survivors know from experience. Even though nobody says it outright, we all feel this invisible expectation to get better, to feel better, and to act like we’re now better. We are supposed to be stronger because of our experiences, which we often are, but the expectations don’t allow us to grieve. I understand. Nobody wants to see or talk to a depressed seven-year-old; and even though we hurt from the inside, we are forced to hold up the stereotype that survivors are strong, happy-go-lucky people. Look at any Children’s Hospital website. Do you see a kid holding their head from pain or crying while playing with their train set?

Survivors like me go through hell and back, but we put on the brave smile for our families and friends even though we live in a body that doesn’t cooperate with all we’d like it to. We swallow our 10 pills in the morning, try to exercise and eat healthy like our doctors repeatedly insist during annual appointments, sleep well without crying, get our work done for class the next day. But at the end of the day, we are not superhuman. It took me a long time to learn this lesson and accept this fact.

Instead, in school, I made up for my lack of physical ability by pushing myself academically. After school, I sang at Los Angeles Children’s Chorus, exercised for an hour, danced and played guitar. And I still do! Sometimes I don’t know why, or even how, but I did it all. It was tough, but I convinced myself that I was tougher. Eventually, I got used to my new life.

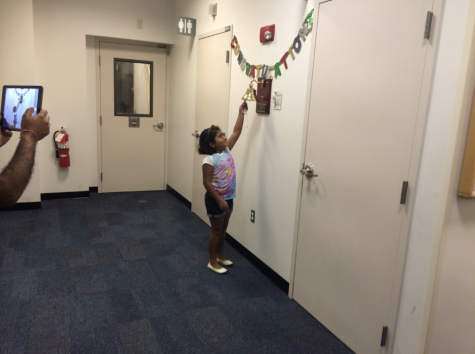

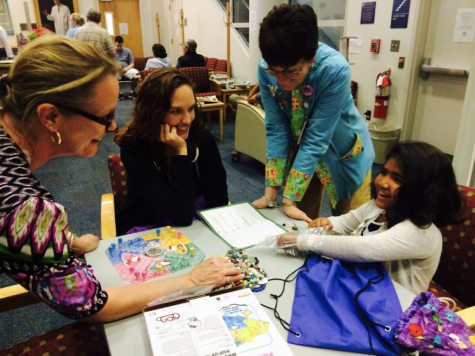

I continued on. While spending six weeks in Boston for proton beam radiation therapy in 2014, I even continued school remotely (I know, I was ahead of the times) and learned ukulele with my friends at the hospital. Because I pushed myself, I am glad to say that I have zero bad memories of my stay in Boston. When I look back, I think about the mint chocolate chip frozen yogurt I insisted on eating everyday, baking cupcakes for my nurses and doctors and taking walks with my parents to buy butterfly earrings in a boutique shop in Beacon Hill.

But I never realized that sometimes pushing myself is not the solution. As I moved into high school, life got harder. I did well, but I had less time to spend on my three-hour guitar lessons, less time for that hour of exercise everyday, and little to no time for me to destress and indulge in my hobbies. I ran from school straight to choir, then to my lifting class, finally came home at 8 p.m. and finished homework. I survived once again, but I was beginning to realize that it was too little to just survive. I wanted to enjoy myself for once and let myself be accepted for what I could do.

I was forced to learn this lesson once again when the world shut down in March of 2020. This time, I faced a new challenge: I developed chronic pain, which restricted my abilities further. Isolation from friends and a normal schedule didn’t help either. Lying down with heat packs and applying arnica gel prevented me from being able to type my essays or join the video meetings. It made me feel helpless. I can tell you that nobody enjoys feeling helpless, especially not survivors.

Again, I was overcome with regret that things weren’t different even though they were completely out of my control. I worked hard, clutching my hands in pain as I wrote notes. I still sang for my choir, LACC, I exercised, but each day felt increasingly harder. It was like trying to grasp onto a cloud while you’re falling to the earth — it felt impossible and overwhelming to even try. Of course, it didn’t help that I pushed myself into taking the “Trifecta” as they call it (AP European History, Honors Chemistry, and Honors Algebra II).

When grades came out, it was the first time in my life when they weren’t the straight A’s I had been used to or that others had expected of me. Everyone told me “It was all because of quarantine,” but I knew this was a long time coming. I couldn’t outrun or out-achieve the limitations of my physical capacity. And that brought me to a new low. It was a moment of deep grief for what my body was not able to accomplish. I had suppressed this loss and mourning inside of me since I was seven years old, but it was now bursting through the seams of my body, literally (in the form of chronic pain) and metaphorically.

I am just now beginning to realize that I need to allow myself to grieve by leaning into the fullness of my emotions, however loud and saddening they might be, by cutting myself some slack from over-committing and by accepting who I am: stories, scars, limitations, exterior, and all.

Although I continue to push myself to excel, I also strive to spend time taking care of myself. If that means crying into my pillow, I cry furiously into my pillow. If it means exercising and putting my homework off for a couple of hours, I lift while blasting music into my noise-cancelling Airpods. And finally, if it means doing more of the things I love, I try not to guilt myself while I draw or sing. My grief can’t wait anymore because that is the only way to heal.

![Dr. Zanita Kelly, Director of Lower and Middle School, pictured above, and the rest of Westridge Administration were instrumental to providing Westridge faculty and staff the support they needed after the Eaton fire. "[Teachers] are part of the community," said Dr. Kelly. "Just like our families and students."](https://westridgespyglass.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dr.-kellyyy-1-e1748143600809.png)

Sunil • Feb 19, 2022 at 2:13 pm

Nitya, thanks for expressing your thoughts. You are a miracle and now an inspiration for others. A big hug.

Peggy • May 17, 2021 at 3:02 pm

Nitya, thank you for sharing your experiences with such vulnerability and authenticity. You’ve learned lessons beyond your chronological age, and the lessons you share are so important for all of us to keep in mind. Here’s to continued healing and self-compassion!