Share their Views or Remain Neutral? The Difficulties of Navigating Politics for Teachers

It was near the end of Westridge’s Modern Middle East class when some students began clicking the leave button to exit the Teams meeting. They had just finished watching a movie and were about to head on to their second class of the day. But as they started to filter out, one student had a quick question to ask the class, “What did you think about the Syrian missile strike?”

The student’s question referred to the United States’ airstrike on January 13, which targeted Iranian-backed militias in Syria. At the time, President Biden’s decision to authorize the strikes came both with enthusiastic support and heavy criticism. The five Modern Middle East students who opted to stay in the Teams meeting started sharing their reactions to the event. In large gallery mode, students’ boxes lit up as they unmuted. Someone brought up what they had seen on social media—how strong supporters of Biden were defending his decision. Another student gave her take on why this decision had been made. Pulling from the historical context that they had covered in past classes, the students had a thoughtful impromptu discussion.

In many other classes, discussions about politics and current events, like the 2020 Election, Capitol Riots, Black Lives Matter protests, and the COVID-19 pandemic, are commonplace and expected from students. Many teachers welcome this kind of discourse, yet at times, it can be tricky. “It’s a high wire act,” said Gary Baldwin, Westridge Director of Upper School, explaining the difficulties of navigating these class discussions. Teachers are often faced with a hard decision: Should they share their personal political beliefs or remain neutral?

The Two Options

Willa Greenstone, Upper School History teacher, has taught at Westridge since 1991. She currently teaches U.S. History as well as Ethics. Both classes are closely linked with current events, so politics is often a topic of discussion. When leading these conversations, Greenstone likes to be transparent about where she personally stands on an issue.

“I do truly believe it’s impossible to be fully objective. History textbooks try to be objective, but they’re not. I think it’s more honest to let students know so that they can parse out what is coming from the facts and what is coming from my view of the facts,” she explained. “People can take that into account and take what I say with a grain of salt.”

Gary Baldwin similarly recognizes the shortcomings of staying neutral as well as sharing one’s views. “My best approach is to say, ‘This is what I think. I’m not telling you what you think, but I think it’s only fair in this conversation if you know where I’m coming from,’” he said.

Others, like April Garcez, Chair of the Social Sciences Department at Mayfield Senior School, leave personal political views out of the classroom. Garcez strives to be as neutral as possible. In the World History and U.S. History classes she teaches, she lays out both points of view and lets her students discuss them with minimal intervention.

“As a teacher, everybody has to have their own opinion, and you don’t want to influence one side or the other because the student is going to feel like you’re for them or against them,” said Garcez. “Those feelings aren’t necessary in the classroom.”

Greg Feldmeth, Polytechnic’s Assistant Head of School and Co-Chair of the History Department, also prefers to remain neutral. He teaches Globalization & Human Rights, Contemporary Ethical Issues, and World Religions. When students ask him for his own view, he responds, “You know what? It’s really more important what you think. What I think isn’t an important factor.”

“The teacher is a power person in the classroom,” Feldmeth continued. “A teacher is giving grades. There’s a possibility that if a teacher shared their political views, then a student might emulate those views to get in good graces with the teacher. I would just be cautious about it.”

Ryan Skophammer, a Westridge Upper School Science teacher, prefers to be open with his views on most politics and sees a danger in being neutral. “I personally don’t believe neutrality exists. I think neutrality is a false premise,” he said. “If a person is neutral in a situation that one group holds to be unjust, then that person is taking a side against that group.”

“I’m not an authority who’s telling students what’s right and wrong,” he continued. “That would be really bad if my expression of opinion is making a student feel they’re either not being fairly treated or they’re not comfortable being in the class.”

Alyssa Hadley Dunn, Assistant Professor of Teacher Education at Michigan State University, explained her concerns with neutrality in an article from the National Education Association. The kind of neutrality that she finds most worrisome involves avoidance of difficult topics. These topics include “‘controversial’ issues – racism, inequity, climate change, or gun violence.”

Garcez, however, still discusses controversial issues while keeping her personal views out of the discussion. She discussed the Capitol Riots with her U.S. History class without sharing her own views. She first gave context to the situation and then started the discussion. Without her input, the class of juniors came to their own conclusion that democracy was under attack.

“That was great for everybody to come to that consensus without me having to talk about it. I was just asking questions,” said Garcez.

But for certain teachers, sharing their opinions serves as a way to build relationships with students. Skophammer, for example, shares his political views in class. “I think it’s important to build relationships where students understand I am also a person who has a particular set of life experiences that have led me to have opinions about things,” he said. “I really want my students to think of me as a person. They need to understand that I’m not just a robot that gives them grades.”

In an NPR interview, Paula Hess, the Dean of the School of Education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, explained the common misconception that teachers who share their political beliefs are trying to indoctrinate their students. However, in a study that she conducted from 2005 to 2009, she found otherwise. Looking at 21 teachers in 35 schools and their 1,001 students, she found “no evidence from the study of teachers who were actively and purposely trying to indoctrinate kids to a particular point of view.” “We think that this feeling that the public seems to have that teachers by definition are trying to push their political views on students is just false,” said Hess.

The First Amendment

“[Teachers] have a right to their political opinions, and they have a right to engage in political speech,” said Belmont University law professor and First Amendment Fellow for the nonpartisan Freedom Forum Institute David Hudson Jr. in an interview with the news journal EdWeek. “Political speech is the core expression that the First Amendment was designed to protect.”

This First Amendment protection for teachers was solidified in the 1968 Supreme Court case Pickering v. Board of Education.

Marvin L. Pickering, an Illinois public school teacher, was fired for writing a letter to the editor that criticized his school board’s allocation of financial resources between the school’s educational and athletic programs. On the basis that the teacher’s First Amendment rights were violated, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Pickering.

But First Amendment rights still come with certain stipulations.

In the Pickering ruling, Justice Thurgood Marshall wrote, “The problem, in any case, is to arrive at a balance between the interests of the teacher, as a citizen, in commenting upon matters of public concern and the interest of the State, as an employer, in promoting the efficiency of the public services it performs through its employers.”

Although a teacher has free speech protection, they cannot say something so offensive that it disrupts their workplace.

Jennifer Cutler, a South Pasadena High School English teacher, explained that when she was getting her teacher credentials, nothing was said about how to discuss politics, but she’s found that staying neutral is a widespread recommendation for teachers. “The guideline, in general, is always to remain as neutral as possible. You shouldn’t be trying to politically sway people or tell people how to vote,” she said. “They’re general recommendations. I’ve never seen anything in writing. That doesn’t mean they don’t exist. I’ve just heard it. It’s just a general guideline for teachers. We need to remain neutral.”

Non-Profit Organizations

Most independent schools are non-profit organizations, and with this status can come additional guidelines on the way in which politics are talked about. The IRS states that all non-profit organizations are “absolutely prohibited from directly or indirectly participating in, or intervening in, any political campaign on behalf of (or in opposition to) any candidate for elective public office.”

Specifically, prohibited participation would include “voter education or registration activities with evidence of bias that (a) would favor one candidate over another; (b) oppose a candidate in some manner; or (c) have the effect of favoring a candidate or group of candidates.”

Baldwin explained how these rules can make navigating politics even harder for the school. “It’s tough for a school which does not endorse one candidate or oppose another to figure out when we are just having an open conversation, and when does that conversation become so one-sided that we are implicitly supporting one side against another.”

“While the school can’t take a position for or against any particular politician, we can absolutely have conversations about politics,” he continued. “That means that as a community, you have to be neutral, but all of the people in the community have to represent the diversity that we’re talking about.”

Student Perspectives

“I don’t think I’ve ever had an instance where teachers were espousing their value system and trying to impress that onto me,” said Molly M. ’22, a Westridge student.

When one of her history teachers talked in length about how difficult it is for women in politics around the time that Elizabeth Warren dropped out of the Democratic primaries, Molly didn’t feel like this teacher was advocating for a particular party or person.

“Someone I look up to who is also a woman, a working woman, explain to me how even though she has worked so hard in her life, there are still times that she still feels very defeated as a woman in this country—that didn’t feel like espousing her politics but more just sharing her experience,” she said. “That is very different than being like, ‘This is my political belief, and you have to feel that way too.’”

Haru T., a Polytechnic senior, explained that he’s fine with teachers sharing political beliefs up until a certain point. “I don’t think that teachers should be scared of expressing their own points of view, but when that is overpowering and tempers the way that students think, it becomes problematic.”

Hadley P. ’21 takes Ethics at Westridge where several varying opinions are shared during class. This dynamic is different from her past history classes.

“We have a pretty diverse group of people [in Ethics], so it’s kind of fun to hear different opinions, different from my own. But this is kind of new to me,” she said. “Usually in my history classes, we all pretty much agree on the same things.”

When most everyone agrees on a certain issue, students with a minority viewpoint sometimes struggle to share beliefs that differ from the rest of their class. Hadley reflected on how it felt in her history classes where most students agreed. “The opinions seem more like facts, so when I have a different opinion, it’s hard to speak up.”

Being in the majority may make students feel more comfortable with sharing their political beliefs while the opposite may also hold true when in the minority. “Most of the time, I’m in agreement with the politics and opinions that I hear,” said Molly M., who identifies as a liberal. “But it would definitely be different for students who fall more on the more conservative side when it came to politics. That could be more uncomfortable for them.”

A Westridge student who requested to remain anonymous has found difficulty in sharing opinions that are uncommon, especially when most of her class is already agreeing on something. “No one has ever really argued about politics when we have these discussions,” she said regarding her history classes. “I don’t think I’ve ever seen a back-and-forth in a discussion. People mostly agree with each other.”

When she disagrees with the majority viewpoint, she keeps it to herself. “I don’t want to get a reputation of someone who has an opposing belief. So I just stay quiet because I don’t want to cause conflict or make someone dislike me.”

In 2020, a free speech survey from the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) with almost 20,000 college students found that six out of ten students said they have not shared certain opinions, fearing how classmates would respond. The largest group that self-censored was “strong Republicans” at 73%.

Haru often shares viewpoints that differ from the rest of his class. “I try to come up with my own ideas, in terms of deducing things for myself,” he explained. “But a lot of times what tends to happen is, especially with left-leaning politics—which Poly is majorly comprised of—it’s based in this moralistic stance where when you disagree, even when you present points of logic, you’ll be demonized in terms of that you must not care about this organization or this group of people if you’re holding these views.”

A recent article from City Journal covered how some private school students feel certain political views are forced upon them, and they fear that speaking up would create conflict with their peers and teachers. The article included interviews from Brentwood School and Harvard-Westlake high schoolers who admitted to “parroting views they don’t believe in assignments so that their grades don’t suffer.”

How Times Have Changed

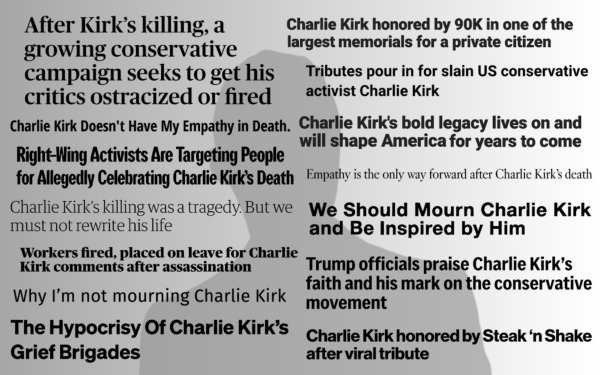

For teachers who do try to remain neutral, the ability to stay neutral has grown increasingly harder over the past few years. Many have noticed that as politics have grown more polarized, neutrality has become more difficult.

During the 2016 presidential race, a group of 10 Teachers of the Year wrote an open letter condemning Donald Trump and his past words and actions. The teachers explained why they decided to take sides when most educators are expected to be politically neutral. The letter, published in the Washington Post, said, “We don’t want to offend our students, colleagues, or community members. But there are times when a moral imperative outweighs traditional social norms. This year’s presidential election is one such time.”

Referring to Trump’s past actions, they continued, “We have to show [our students] that hatred, sexism, racism, disrespect, and threats of physical violence are not okay… As teachers, we strongly oppose Donald Trump.”

Gigi Bizar teaches a Seventh Grade History class that spends a large part of the year discussing the Holocaust. She has also found it harder to avoid sharing her political beliefs in recent times. “As a teacher or as an administrator, you’re not supposed to share who you would vote for,” she said. “But that all went out the window this year.”

Willa Greenstone, once able to easily discuss two sides to a political issue, has also struggled with this. In 2003, at the beginning of the Iraq War, she could explain the arguments for and against the U.S. going into Iraq although she herself didn’t support it. She felt comfortable sharing the two different factual points of view. But now, she believes, things have changed. “The United States is currently in a different place where we have people who are being persuaded by untrue things, false news, conspiracy theories, etc.”

Sometimes in class discussions, Greg Feldmeth will encounter a student who shares an opinion based on false facts. Feldmeth approaches this by encouraging the student to further research the events at hand. He rarely contradicts someone directly in class, and he prefers one-on-one conversations once class is over. “I would never want to embarrass anyone because of their viewpoint,” he explained. “But if someone is spouting untruths, then I think it’s important to push back at that.”

Community Norms

The schools interviewed in this article do not have formal rules outlining how much teachers can share their political views; instead, their community norms and values often inform these boundaries.

Gary Baldwin explained that one of Westridge’s goals is to make sure no member of the community feels silenced in expressing their opinions. Westridge’s core values are integrity, respect, responsibility, and inclusion. In class discussions, an emphasis is put on inclusion. Teachers can accordingly determine what that entails in their classroom.

“Sometimes teachers will approach that by saying, ‘I’m going to maintain an outward facade of total neutrality,’” said Baldwin. “And other teachers may feel that the best way to do that is to support a free exchange of ideas so that everybody feels as though—even though we may disagree about things—this is a safe space for us to express ourselves.”

At Polytechnic, their Honor Code outlines the school’s values. It states, “As a member of the Polytechnic community, I will act to foster inclusion and to promote excellence in all that I do. I commit to approach my decisions with integrity, kindness, and generosity both on and off campus.”

Greg Feldmeth explained that these values inform how teachers choose to teach. “All of those values indicate an openness to ideas without being hypercritical of them. I think a school’s values are representative of the way teachers teach,” he said. “At Poly, we’re about open inquiry—that’s our approach.”

At Mayfield, they have a set of seventeen community norms that determine how they approach class discussions. Agreed on by the community, these norms set the foundation for how each class is conducted. Garcez gave some examples of these: “to be respectful, to understand, and to speak in the ‘I’ statements. That’s the context to which everybody agrees upon. And then we move forward on that.”

Ryan Skophammer appreciates how there are no strict rules for teachers that tell them how little or how much to talk about politics. They instead get to decide for themselves what this looks like. “Teachers are professionals, and they understand what the appropriate boundaries are,” said Skophammer. “I think that the Westridge administration isn’t codifying those boundaries. Teachers are capable of recognizing what those boundaries are and should be.”

Katie is a senior, and this is her fifth year on Spyglass and third year as an Editor. In her free time, she loves playing guitar, writing, and doing calligraphy.

![Dr. Zanita Kelly, Director of Lower and Middle School, pictured above, and the rest of Westridge Administration were instrumental to providing Westridge faculty and staff the support they needed after the Eaton fire. "[Teachers] are part of the community," said Dr. Kelly. "Just like our families and students."](https://westridgespyglass.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dr.-kellyyy-1-e1748143600809.png)

Amy Chen • Apr 13, 2021 at 10:38 am

Katie , this report was in such detail. Really good job.