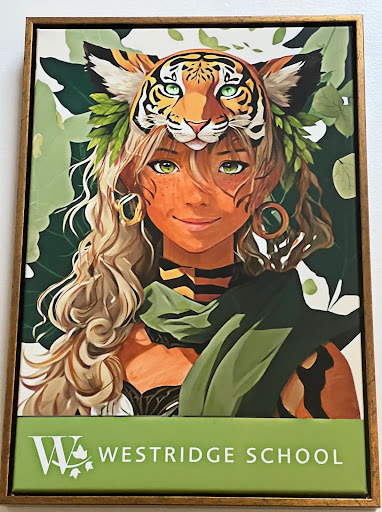

It was Wednesday, November 24 in 2024. That day, I walked into Mudd, I stopped in my tracks. I was face to face with a peculiar art piece. It was a headshot of a girl with a slight smile, wearing what appeared to be a tiger face on her head. She was wearing a dark green scarf, but that was all I could discern from her clothing. Her eyes were bright green, but the uneven blending and saturations of the pupil and iris made it feel devoid of feeling. The background had vague forms of leaves or greenery. At the bottom, it was branded with the Westridge logo. The painting was uncanny, perfect yet not. Areas lacked rendering where it was necessary. The lighting on the girl’s face didn’t correspond with the background. It felt like a bunch of different elements cut and pasted together without much thought. Immediately, I suspected it was AI-generated.

This made me wonder what teachers think about AI art. After all, AI art is images created by generative AI that uses mathematical and statistical algorithms to analyze datasets of existing images and identify patterns before creating “new images.” A recent example of this is the trend of creating AI-generated art in the Studio Ghibli art style. Many argue that it is disrespectful to the work of the studio’s artists who have practiced and worked on the unique visual style that is Ghibli. Others believe that it allows the Ghibli style to be more accessible to fans and appreciate the Ghibli aesthetic in a new way.

Upper and Middle School Visual Arts teacher, Ms. Jenny Yurshansky advocates using AI as a “tool,” to help explore new and experimental ways of how artists create and develop art. She referenced artist Janice Gomez whose art projects use her family photos to create AI generated images to fill up the gaps in her family history. Ms. Yurshansky said, “Our collective memories are being inserted into her family photos,” prompting discussion around what is real or authentic. Ms. Yurshansky encourages students to think critically about using AI prompts, to push creativity and question society, the world around us, instead of using it as a shortcut.

I can imagine myself using AI as a starting point to create an image. The art piece hanging in Mudd could be considered a first draft to which I might revise in color, composition, and textures. This art piece has the potential to serve as a brainstorming idea that could be fleshed out and executed with a human hand.

The exercise had me wondering: if students are allowed to create artwork with the help of generative AI, should students also be allowed to write their essays with generative AI’s assistance? In both cases, AI uses algorithms to find patterns from datasets. Both use existing human work belonging to someone else to “create” something new. If students are allowed to explore AI as a tool in art, shouldn’t the benefits of AI be available in other subjects or assignments, like English or computer science?

At Westridge, there is no institutional-wide AI policy. The English and History departments do not allow generative AI such as ChatGPT to be used in any assignments. Both departments emphasize the importance of originality and developing writing skills, though students are allowed to experience “limited” AI usage in history classes. In computer science classes, students do have opportunities to use generative AI and are at times even encouraged to explore it, to create partial codes to construct the main code. However, the art department has no generative AI policy. Across departments, approaches to generative AI in the classroom differ, according to a previous Spyglass article, “Westridge Responds to Generative AI’s Impact on Teaching and Learning”: “those who embrace AI as a teaching tool have done so in ever-increasing numbers and ways, while some teachers have taken a more cautious approach toward AI their classrooms.”

Teacher concerns around students’ writing development are valid. However, Westridge’s lack of AI usage policy and inconsistent attitudes towards AI prevent students from learning how to use it effectively and ethically; the school should have a clear policy that teaches students how to use AI as a creative and educational tool across subjects. AI isn’t going away any time soon, and the longer Westridge waits to confront its presence in education, the further behind students will fall in harnessing its value.

The biggest concerns seem to be around writing, and for good reason. Upper School History teacher Ms. Sandy de Grijs, said, “…writing isn’t only about the final product, but it’s about the process. And so, the learning happens in the process of [students] using [their] brains to work on the writing and editing and all those pieces, and so, from our point of view, that’s the most important part.” She understands the temptation of students to use a tool like ChatGPT but truly believes that AI stops students from engaging in their own critical thinking and from developing their unique written voice.

The article Using AI ethically in writing assignments by Center for Teaching Excellence at University of Kansas makes a great point, viewing writing as “process and product” and “a process involving many types of collaboration.” This collaboration can include the feedback of teachers, classmates, friends, and even generative AI. “They integrate the style and thinking of sources they draw on.”

While teachers in writing related subjects fear that AI bypasses the thinking process involved in shaping and refining ideas and arguments, students can learn to use generative AI effectively and ethically when teachers no longer view writing as an isolated activity, but as a process that engages multiple sources, ideas, tools, data, and other people in various ways. Generative AI is simply another point of engagement in that process—at the initial stage: generating ideas, narrowing the scope of a topic, researching, outlining, creating an introduction; during the process: creating titles or section headers for papers, helping with transitions and endings, getting feedback on details or on the draft.

Dr. Zanita Kelly, Director of Lower and Middle school, did confirm that the piece was AI-generated. She believes that AI art provides new perspectives into the world and encourages the exploration of art in technology and generative AI art supports Westridge’s mission of forward-thinking and curiosity. “AI art deserves to be displayed in Mudd because it represents an evolving form of creativity that merges technology with artistic expression,” Dr. Kelly said. She wants everyone engaging with AI to “think critically, creatively, and ethically about technology, ensuring they are not only prepared for the future but also capable of shaping it with purpose and integrity.”

I admire her courage in taking the step to promote AI in the Westridge community that still lacks an AI use policy and has inconsistent attitudes towards AI.

I believe that AI can help students write essays with the right prompts, ones that require students’ careful thoughts. They may have potential as a tool for generating ideas or providing a starting point for organizing thoughts, a process that could be taught to future generations in Westridge learning. The Internet allowed students access to information at their fingertips, and the graphing calculator changed the way people learn and see math. In the same way, AI tools with clear guidelines and transparency could also potentially revolutionize new ways of learning. Turning in unedited AI-generated work as your own work will and should never be allowed. Learning how to use AI effectively is something that will be necessary in our future, and a school-wide AI policy that supports AI as a creative and educational tool will help students use it ethically and effectively.

![Dr. Zanita Kelly, Director of Lower and Middle School, pictured above, and the rest of Westridge Administration were instrumental to providing Westridge faculty and staff the support they needed after the Eaton fire. "[Teachers] are part of the community," said Dr. Kelly. "Just like our families and students."](https://westridgespyglass.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dr.-kellyyy-1-e1748143600809.png)