As Piper* reviewed her Spanish notes for an upcoming group presentation in March, she stumbled on a piece of her partner’s writing. To Piper, it felt like it “was written with ChatGPT.” She said the writing “was a bit too niche and did not follow what we had learned so far.”

Feeling that the assignment and her partner’s component of the writing were “low stakes,” Piper didn’t voice her suspicions to her partner or teacher. Despite this, she said, “I was very uncomfortable [with] it. It doesn’t feel good knowing that a part of your [group’s] work was made artificially.”

This was not Piper’s first time seeing a classmate use generative artificial intelligence to complete an assignment, nor would it be the last. “AI usage is definitely increasing in ways that I wasn’t expecting,” Piper noted. “It used to be for learning material but now people use it like they use the internet—to answer the most basic questions. ”

Since ChatGPT’s launch in November 2022, AI has become omnipresent in daily life. Almost three years on, AI startup OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT, reports that ChatGPT has around 200 million users weekly. The platforms have already impacted the way humans engage in the world—and Westridge teachers and students are experiencing those impacts daily inside and outside of the classroom.

Those who embrace AI as a teaching tool have done so in ever-increasing numbers and ways. Teachers use it to create more effective lesson plans, generate worksheets and projects, and even help write comments or letters of recommendation.

Upper School Mandarin Teacher Ms. Annie Choi, whose first language is not English, uses ChatGPT to review her grammar and make her writing flow “more authentically.” However, she emphasized that the content of her writing is her own. “I would definitely not let AI replace me and write comments for students because that loses the personalized touch in comments to show you know the student and how they are doing in class,” said Ms. Choi.

In lesson planning, Ms. Choi treats ChatGPT “as one of her colleagues [or] co-workers.” She said, “Just like you cannot steal things from people and people’s ideas, I think it’s good to use AI as a brainstorming tool, like a start[ing] point, but not use it to generate everything.”

Although Ms. Choi does not allow her students to use ChatGPT or Google Translate, she is very transparent with her students about how she uses AI. Spyglass Staffer Hermione W. ’27, one of Ms. Choi’s students, said, “If [using ChatGPT] is more efficient, she might as well. I don’t really care—I have to get the same amount of work done.”

Similarly, Upper School Computer Science Teacher Mr. Daniel Calmeyer uses ChatGPT in his computer science classes to quickly generate code once he has taught the basic concepts to students. Sage K. ’26, who took his AP Computer Science A class last year, said, “For me, especially with computer science, [AI] is pretty normal…You can’t know everything—and at that point, sometimes it’s just easier to look it up with AI.”

Mr. Calmeyer also uses ChatGPT to aid him in writing comments and recommendation letters. He talks aloud to the AI voice mode while he is brainstorming ideas, and Chat-GPT converts it to writing. While he still edits the final draft, for him, ChatGPT is like “a much better version of a secretary.”

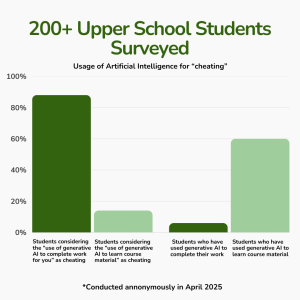

Student use of AI is also on the rise, blurring the lines between ethical and unethical academic use. From over 200 Upper School student replies in Spyglass’s spring survey on cheating, almost 88% of respondents categorized “use of generative AI to complete work for you” as cheating, while only 6.1% of students felt “use of generative AI to learn course material” was cheating.

When asked what kinds of cheating students had participated in, 14% of respondents said they had used generative AI to complete work for them. A much larger 60.1% of students said they had used generative AI to learn course material.

Despite several foreign language teachers informing Spyglass that the use of AI and Google Translate is expressly forbidden in their classes, 181 out of 228 students admitted to the use of a translator, the highest number of all the different types of cheating. One student who admitted to using Google Translate for some homework instructions, despite her teacher’s expressed policy against such tools, does not believe she cheated.

The distinction between the ways AI is used for academic purposes is significant and not always clear between students and teachers. The rising use of generative AI is often not perceived by students as an act of cheating, especially when it comes to using AI as an efficiency tool, starting point, or way to better learn and comprehend new concepts. Some students don’t see their use of AI as malicious, but rather as a way to fill in the gaps of their understanding. An unnamed sophomore said, “I’ve used ChatGPT to help me generate new ideas for my paper. My starting point will be ChatGPT, and then I’ll find sources that connect to it.”

Liv C. ’28 believes that ChatGPT can be helpful in better understanding topics like historical time frames, finding “trustworthy” articles, and can “save a lot of time in terms of studying for classes.”

For the students who use AI to supplement their work, ethics and fairness are not at the front of their minds. Instead, it’s efficiency.

An unnamed senior said she “only use[s ChatGPT] for math. I only use it for homework.” She turns to AI “because it takes a long time to do and [feels] like [she] has to learn on her own to be able to do homework.” She added that using AI to complete assignments has not become a habit, as she restricts her usage to solely math assignments. Her usage is motivated by both a desire to learn math concepts, and to complete homework faster.

Generative AI’s use in academics raises concerns of academic integrity and fairness, on the part of teachers and students. Sophomore Avin M. ’27 said, “When people use it to write their papers for them or to give them an idea to expand on, it’s definitely cheating and not fair to the kids who have worked from their own ideas and own writing.”

Just as not all students see artificial intelligence in the same light—some eager to embrace the tool and others shunning their peers for taking a shortcut—teachers’ views also widely differ.

Upper School English Teacher Ms. Molly Yurchak has both pedagogical and philosophical concerns about AI, arguing that its use deprives students of meaningful learning experiences and creates an uneven playing field for those who write without it. “The idea that students who are not using this technology might have a lower grade than someone who has used it and has fooled me is so upsetting,” said Ms. Yurchak.

In response to the growing use of AI, Ms. Yurchak has changed the ways she has students write. This year, in Ms. Yurchak’s class, both her seniors and sophomores write essays on a platform called Exam.net, in hopes of eliminating the temptation to consult AI. The program locks students into a screen with a writing page, prohibiting students from receiving messages or switching to other tabs.

While Olivia C. ’25, a senior in Ms. Yurchak’s Women of the Novel class, finds the format of Exam.net “annoying” and “tedious,” she said, “I understand a need for a software that ensures all students are not doing anything that they might regret later or that will harm their own learning outcomes.”

Last year, Ms. Yurchak had her students exclusively hand-write essays in Westridge’s Writing Center. She continued, “I really just want my students to have an authentic education, and I think AI is a real temptation to shortchange that process.”

While some teachers like Ms. Yurchak have taken a more cautious approach toward AI, other teachers across departments have explored different ways of how, or whether, generative AI might belong in their classrooms.

In 2023, Spyglass interviewed Westridge Computer Science teacher Autumn Rogers, who was in full support of using AI, particularly ChatGPT, in the classroom when it made its debut.

At the time, allowing students to explore using ChatGPT felt like a way to inform them of the power of AI and its effects on technology and learning. Today, Ms. Rogers feels differently. “Last year, I was a little bit all-in on [AI], trying to see how it worked, and it seemed to me as though it did degrade the learning outcomes,” she said. “So, I have significantly changed my policy and will probably preserve this policy.”

Even within the same subject area, teachers take varied approaches to incorporating AI in the classroom. Mr. Calmeyer continues to permit and encourage the usage of AI in his advanced Computer Science class, Full Stack Web Development. “In Full Stack Web Development, using AI is completely allowed…[students] can apply it to the projects they’re working on,” he said.

Mr. Calmeyer makes a clear distinction between his advanced class, Full Stack Web Development, and his introductory class, AP Computer Science A, where students do not use AI. Calmeyer explains that in a more beginner-level class, it is crucial to learn the fundamentals without being reliant on technology. He also raises ethical concerns about AI use in collaborative settings: “When you’re using the artificial intelligence as a filler for your own knowledge, how do you then communicate that to the other people that are working on the task with you?”

Maddie M. ’26, a current student in Full Stack Web Development, said, “In AP CSA, you could get ChatGPT to do everything for you; but in Full Stack [Web Development], even if you are using AI, you still need a baseline of coding knowledge to conceptualize the project. We’re using it as a tool, but the idea, the planning, and everything else is still us.”

Varying Policies

Currently, AI policies for student use of AI vary across classes and departments. Director of Teaching and Learning Mr. James Evans and the EdTech team—a group of tech partners operating with the philosophy of teachers helping their peers—researched and considered different AI philosophies, offered teachers several different options for AI policies, and let them choose which one they wanted to implement in their classroom.

There is currently no professional or academic policy on faculty and staff use of AI. However, Director of Technology Ms. Sally Miller, who leads the EdTech team, has guided faculty and staff through several sessions of “AI training” with the goal of “increasing the AI literacy by developing a shared baseline understanding of AI through curiosity and hands-on exploration.”

She expects that as AI tools continue to evolve, both teachers and students will also need to adapt. “[AI is] an incredibly disruptive technology…but [it] is not going anywhere. So we do have to figure it out, [and] we’re just committed to giving each other grace and being supportive and kind with students,” said Ms. Miller. “I hope we can figure it out together and really be transparent and understand that it’s hard for everybody.”

Upper School Science Teacher Dr. Ryan Skophammer echoed her statement, saying that while he is unsure of how classroom and professional policies may change, he hopes “we as a community do a good job of communicating our values around this, [so] it then becomes our guide for how we all behave.”

*This name has been changed to protect the anonymity of the source, in accordance with Spyglass’s Anonymous Source policy.

![Dr. Zanita Kelly, Director of Lower and Middle School, pictured above, and the rest of Westridge Administration were instrumental to providing Westridge faculty and staff the support they needed after the Eaton fire. "[Teachers] are part of the community," said Dr. Kelly. "Just like our families and students."](https://westridgespyglass.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dr.-kellyyy-1-e1748143600809.png)

Jbueno • Apr 29, 2025 at 1:16 pm

Excellent article!

katie • Apr 28, 2025 at 9:49 am

Isa ate it up with this art!!! great article 🙂