Clear and timely communication is essential to helping communities stay informed and prepared during a crisis. When Westridge was closed for four days due to the nearby Eaton fire, students, parents, and faculty looked to the administration for updates on closures, expectations, and the return to school.

In the transition back to school, the administration sent a total of 13 official emails to parents, students, and faculty, although teachers may have received additional updates from their respective division directors. However, compared to the many emails sent to parents, Upper School students received only three emails, and four for seniors, before returning to school: one from Head of School Ms. Andrea Kassar on Wednesday, January 8 and two emails specifically addressed to students from Dr. Arias later in the week. Additionally, the college counseling office sent one email to seniors regarding potential delays in sending application materials.

Between Tuesday, January 7 and Tuesday, January 14, Upper School families—both students and parents—received four to five emails. There was also additional communication, with four extra emails directed only to parents and two extra emails solely to students. While the administration maintained consistent communication with parents, some students were left feeling confused about class and homework expectations, as well as what school would look like for the following week.

Ms. Kassar sent parents an email on Saturday, January 11 providing important information about returning to school, including guidelines regarding uniforms, attendance, and classwork expectations. In terms of schoolwork, Ms. Kassar’s email stated, “Please be assured there will be no tests, quizzes, or projects due in our first week back.”

Upper School students received a direct email from Administrative Assistant to the Upper School Ms. Kali Spicer, stating, “Your teachers are planning for no tests, quizzes, or large assignments this week.”

The email did not explicitly mention homework. Without any clear language regarding homework, students returned to school feeling anxious about the homework expectations.

Upper School Dean of Student Support Ms. Bonnie Pais Martinez sent a student bulletin to Upper School advisors, along with instructions to pass on the information to students during advisory on Tuesday, January 14, stating, “We will ease back into academics with a revised schedule. There will be no homework or assessments in the coming days.” Because students did not receive the information directly, and because some advisors didn’t fully share the messaging, students were unclear about homework expectations and left without recourse.

“I felt kind of confused because in some classes I was doing actual homework and classwork that was integrated into the curriculum. But for other classes, I could just play Roblox,” said Isabelle Y. ’27.

“I was a little confused…because I got homework from a math teacher as well as classwork, and I know that they said we’d transition to preferably just classwork,” Amelie S. ’28 said.

Sarineh G. ’28 said that while most of her classes were relatively relaxed, one of her teachers still assigned both homework and classwork as usual. Frustrated by the inconsistency, she said, “There was supposed to be no homework, but I got homework. Why did I get homework?”

“Some teachers have respected the no-homework policy and haven’t given us any homework, but I’ve had some teachers who assign regular homework, and I think that’s a little unfair,” Amelie S. ’28 added.

In addition to the confusion about homework, some students were unsure about what to expect during class time. In an email to Upper School students and faculty on Tuesday, January 14, Dr. Arias described that the special schedule aims “to allow space for connection and processing.” Most students agreed that time allotted for advisory and class meetings made the transition back to school easier, but differing levels of intensity only made for a jarring experience. Some classes remained focused on processing the event; others resumed their standard curriculum.

“They didn’t have a…schoolwide plan of what teachers should be doing…teachers decided what they wanted to do,” Sofia K. ’25 said.

Additionally, the no-homework policy, which was meant to alleviate stress, only created more when the scheduling of tests and assessments resumed the following week.

“All of the classes that one week when we came back were extremely chill. But I think one of my complaints was that they would assign tests the next week.” Isabelle Y. ’27 continued, “So it’s kind of counterintuitive. You have no homework, but it’s like you [actually] have homework [because] you have to study for the test next week.”

Some students suggested that sending all major updates to both parents and students could have reduced the confusion. “I think no matter the situation, even if you’re not in danger…all students should get the same emails parents do,” Soledad B. ’28 said. “Then it makes you independent, and you don’t need to rely on your parents [for information].”

Initially, students received direct updates about school closures. Between January 7 and 9, students, faculty, and parents were all included in schoolwide emails regarding the fire’s impact. However, after January 9, direct communication with students became less frequent, and most critical updates regarding the school’s reopening were sent only to parents. The administration’s email on Saturday, January 11, stated that students would return on Tuesday, January 14, but students did not receive this update directly. Instead, many learned about it from their parents or peers.

“I think some of [the emails] were directly [communicated to students], but there was one email about coming back to school that I didn’t see, so my mom told me that one,” Isabelle Y. ’27 said.

“We should have the responsibility to be informed of the situation and what’s going to happen in the future,” Tiffany W. ’28 said.

Teachers mostly thought that the administration’s communication was clear, while some noted there may have been difficulties in ensuring consistency. “I thought [the communication] was clear, and I moved forward and did that, in terms of no homework,” Upper School History Teacher Ms. Sandy de Grijs said.

“For me, I felt very supported. And I felt very much like I could figure it out and do it in a way that made sense for my own class,” said Upper School History Teacher and Department Chair Ms. Melissa Kelley. However, she pointed to the possible difficulty of ensuring uniformity, stating, “Some teachers had to evacuate and didn’t have easy access to Canvas to update their coursework, which may have contributed to confusion.”

Director of Marketing and Communications Ms. Kim Kerscher acknowledged the challenges of crisis communication, noting that the school aimed to be cautious about what was communicated directly to students during an uncertain and evolving situation. “In the fires particularly, we were a little more cautious [in our communication], knowing that it was a really frightening situation that was changing in the moment,” she said. “Until the situation started to settle down a bit, we were just going to adults and letting them kind of decide what their student was ready [for].”

Reflecting on the overall experience, Ms. Kelley stated, “One thing that was highlighted a lot is that the number one thing is the safety of everyone.”

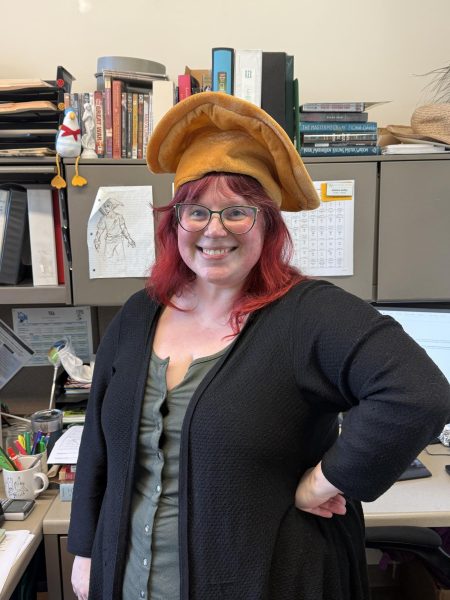

![Dr. Zanita Kelly, Director of Lower and Middle School, pictured above, and the rest of Westridge Administration were instrumental to providing Westridge faculty and staff the support they needed after the Eaton fire. "[Teachers] are part of the community," said Dr. Kelly. "Just like our families and students."](https://westridgespyglass.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dr.-kellyyy-1-e1748143600809.png)

anonymous • Jan 31, 2025 at 2:29 pm

YESSSS ATEEEEE i completely agree the ppl quoted have great points and interesting perspective on post-fire communication!!!!!