Warning: This review includes plot descriptions and integral details of the film.

The first time I watched Coralie Faregat’s The Substance (2024), I felt like nothing could have prepared me. The movie moves quickly from genre to genre in a way where you feel like you’re watching a Broadway stage change through the acts—from a bright workout film to a brutal car crash drama to a medical show and back again to a workout film.

And you still haven’t experienced the trademark gore.

Overall, this film was a lot. The Substance captures themes of aging, self-doubt, and the intense downward spiral of a TV-show star to tell a story—but if it’s a feminist story, that’s where I have my doubts.

The film tells the story of aging aerobics TV-show star Elisabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore), who gets fired from her job after turning 50. In the words of the TV-show executive Harvey (Dennis Quaid) who fires her, “At 50, it stops.” After she asks him what “it” is, he becomes distracted and leaves. When Harvey uses the term “it,” he implies that Elisabeth’s attraction and marketability are fading—a harsh reality for many women in Hollywood.

On the drive back to her apartment after this torturous conversation, Elisabeth watches a billboard of her face get torn down. Fearful that her long legacy with the TV studio may be forgotten, she takes her eyes off of the road and is crashed into by another car.

At the hospital, she is reminded that it is her 50th birthday and begins to cry. Elisabeth is told that she can leave, and she heads home—but finds a mysterious USB drive in her pocket.

Once in her apartment, a shrine to her aerobic TV persona, Elisabeth watches the video on the USB drive. The video promises—in large, bold letters—“YOUNGER, BEAUTIFUL, PERFECT.”

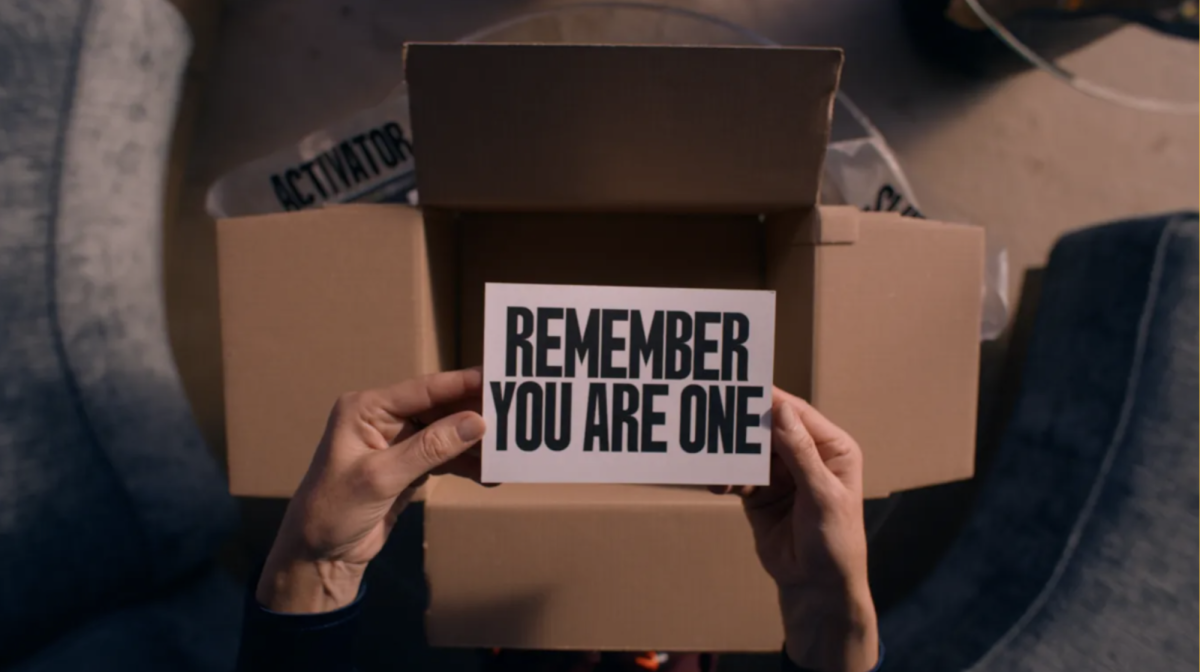

After watching the video that addresses exactly what Elisabeth desires, she promptly calls the number advertised and signs up for “THE SUBSTANCE.” The caller on the line gives her an address, and Elisabeth quickly drives over and retrieves a box of supplies.

Once home, the horror aspect of the movie begins to emerge. From the box, Elisabeth pulls out long needles, eerily empty jars, and finally, an artificially-green vial labeled “ACTIVATOR,” each further foreshadowing the countless novice medical procedures to be performed throughout the film. So please, if the sight of any of these products makes you wary, I’d urge you to cover your eyes for the next few minutes.

The gore was one of the least advertised parts of the movie, but it is what I remember most about the film. I could barely rewatch the trailer without remembering all of the bloody, bony details.

As someone who can barely watch an episode of Grey’s Anatomy or Botched without cringing over the miniscule amounts of blood and guts depicted, watching The Substance was like diving headfirst into a pool of ferocity. Within the first 30 minutes, I already witnessed Elisabeth’s “rebirth”—an almost four-minute long scene where Sue, played by Margaret Qualley, emerges from Elisabeth’s back—which is defined by its realistic visuals and nausea-invoking sound design. I won’t exactly describe it to you, but it was a difficult watch.

In fact, the graphically gratuitous gore is the most clear-cut downfall that Faregat’s sophomore film succumbs to. While The Substance attempts to showcase the ruin of an aging woman on her journey to promised “PERFECTION,” the gore makes it almost clownish—and not in a way that emphasizes the exaggerated reality of plastic surgery. Some scenes in The Substance made me question if I was watching an extended trailer for Stephen King’s It.

Still, in a world of female-targeted vanity treatments with “medical” benefits—think GLP-1 use for celebrities, the popularization of the waist trainer, and Demi Moore’s own blood-sucking therapy performed by medical leeches—The Substance does a fine job of portraying the temporary effects of “THE SUBSTANCE”—until things start to go bad.

After the “rebirth,” an unconscious Elisabeth is left with an open gash from the nape of her neck to her lower back, but is joined by a younger, more attractive counterpart who names herself “Sue.” But while the two are constantly reminded “YOU ARE ONE” and that they must switch every seven days, Sue overstays her welcome, leading to grisly consequences for Elisabeth.

While The Substance does portray the downsides and dangers to many cosmetic procedures, Elisabeth’s transformation into a monster is more gruesome than most, making it extreme and unrelatable. And even when Elisabeth thinks that she has nothing more to lose, she calls the black market company to “terminate” Sue, but she cannot go through with it. Elisabeth desires the attention and praise that Sue gains and is not ready to live without it, even as her monstrous state worsens.

At the end of the movie, I found myself confused with Faregat’s motivation for creating it. The Substance doesn’t fully commit to being either a cosmetic-surgery cautionary tale or covering body dysmorphia in a feminist lens—and let’s be honest, it portrays neither side very well.

If The Substance wants to be the feminist film it’s praised as, showcasing the reality of body dysmorphia and society’s expectations for women aren’t enough.

When I think of a feminist film, I think of one that prides itself as being fearlessly feminist. I think of Little Women, where Jo defies societal expectations to become a writer; Everything Everywhere All at Once, a touching story of a mother and daughter facing what it means to be a person in the universe; and even Frozen, which challenges the typical Disney trope of a damsel in distress.

The lack of character development for female protagonist Elisabeth is another large issue of mine. The movie begins with Elisabeth feeling insecure enough about her body to commit to a body-altering treatment. During the course of the movie, she doesn’t grow from that decision. She is stuck in this choice—and cannot continue regular life. If second-wave feminism has taught my generation anything, it’s that the man is trying to keep us down. News flash, boomers, he still is, but we’ve moved on.

And, even though The Substance has scenes that embody body dysmorphia and the female curse of never being good enough, it isn’t unapologetic in its nature. In fact, it constantly objectifies Sue. Close-ups of her body during aerobic workouts, full-body scenes of her stretching after getting out of bed, and even not-so-tasteful nudity felt more like leering than observing.

Even if these scenes are meant to show the harsh reality of what is perceived of women and girls, the shots felt like they did more harm than good, as viewers were forced to dig deeper for the metaphorical meaning of these shots, and they might give the false impression that there is no deeper meaning to the movie.

(Still courtesy of the Festival de Cannes)

Despite many of its faults, I would still recommend The Substance. Even if the film isn’t entirely fleshed out, the body horror and journey that Elisabeth goes on is an entertaining watch. When I’m looking for a horror movie, I find myself going for cliché, showy films, and The Substance was exactly that.

The Substance was a maximalist film in the most minimal way possible. Each still features contrast, eye-catching colors, and dynamic portrayals of characters, which make for a good viewing experience, but most scenes feature only one character, and the dialogue is minimal. This is a design choice that I appreciated. I also appreciated the scenes punctuated by long pauses of silence—which gave the viewer time to absorb the visually rich depiction.

The Substance is a classic body-horror movie, but it won’t leave you with a revelation. If you go in with the high expectations of the third-wave feminist trailblazer film that it’s sometimes portrayed as, yes, you will leave disappointed.

The notable elements of this film (irony, minimal conversation, intense colors, etc.) will leave you with something—whether it be a deeper understanding of the “female experience” or a new 1-star review on Letterboxd, I cannot tell you. Still, the gore, fierce aesthetic, and often minimal dialogue are meant to call forth emotion, and that is exactly what they do.

![Dr. Zanita Kelly, Director of Lower and Middle School, pictured above, and the rest of Westridge Administration were instrumental to providing Westridge faculty and staff the support they needed after the Eaton fire. "[Teachers] are part of the community," said Dr. Kelly. "Just like our families and students."](https://westridgespyglass.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dr.-kellyyy-1-e1748143600809.png)

Anonymous • Dec 19, 2024 at 9:41 pm

Wow! What an insightful review, touches a lot of great points. Well done!