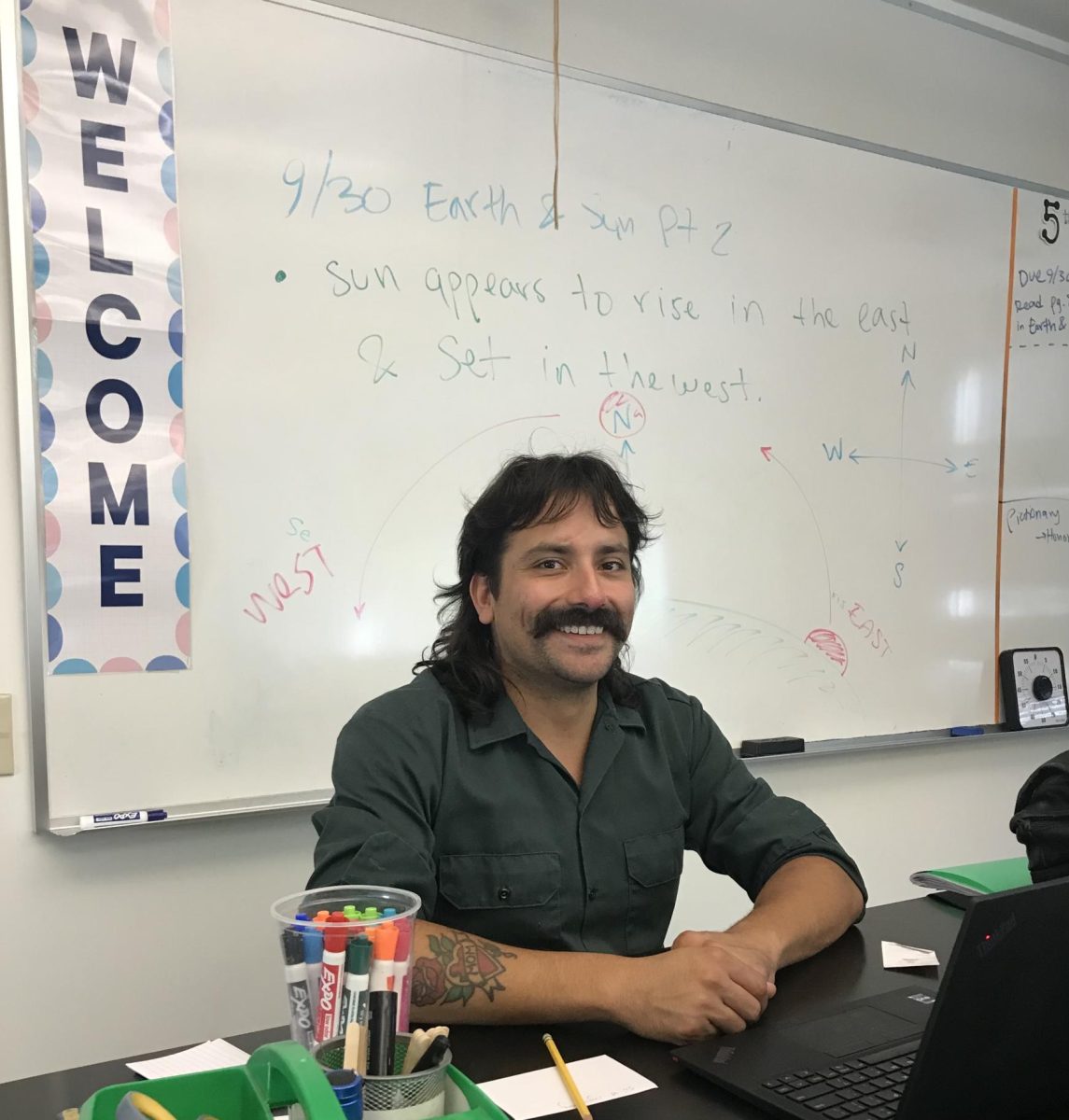

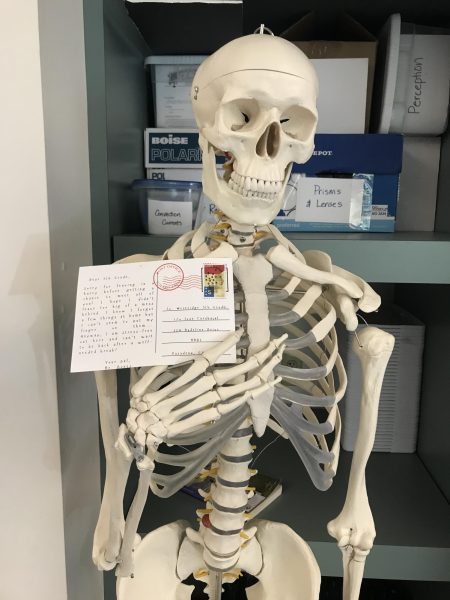

Yellow caution tape and a bunch of eager fifth graders. In Mr. Carabajal’s classroom, these two seemingly different sights merged together, and I found myself in the middle of a crime scene: Mr. Bones, the class skeleton, was missing. Who doesn’t love a good mystery? The room was crowded with kids eagerly searching for clues. In the middle of the joyful chaos was Mr. Ivan Carabajal, fifth and sixth grade science teacher, less than a month into his Westridge career, surrounded by a flock of kids intently asking him questions about their every suspicion. Instantly, I wished that he was my fifth grade science teacher.

Within minutes of our conversation, Mr. Carabajal’s extensive passion for science was evident. His smile was contagious as he described his work at the National Park Service and his most recent science experiment for his students. Nearly every section of the room was where a science project had taken place.

It is hard to believe that he did not always imagine a scientific career for himself. Intending to major in philosophy, he considered his interest in science as nothing more than a hobby. The “static” experiences that lacked “hands on stuff, things in front of your face” initially deterred him from considering a professional career. Thankfully, Mr. Carabajal took a geology class in college and changed his major to earth sciences a week later. He smiled as he mentioned his friendship with his first geology teacher.

As a teacher, he prioritizes developing students’ love for science by presenting topics in a fun and engaging way. From solving a crime scene to predicting the difference of throwing a rock versus a piece of paper, the hands-on approach keeps the kids engaged. He aims to teach his students that science is everywhere and that everyone is a scientist. “We’re all here on Earth, just on this rock, spinning. We could either be scientists and figure it out, or wait and have everyone tell us everything is true,” Mr. Carabajal said. I think we all know which option he wants us to choose.

Mr. Carabajal does not keep the joys of science to himself and his students. He completed his master’s thesis from the University of Cincinnati seeking to understand how students with disabilities navigate through the physically challenging earth science requirements. They are often handed a worksheet and told to watch, an isolating experience. “This idea that people are not searching for a career academic study in earth sciences because of something out of their control did not sit right with me,” said Mr. Carabajal. Currently, he is working on his dissertation: developing a set of guidelines around how to make environments more inclusive. He plans on presenting his findings to educational departments.

At Westridge, Mr. Carabajal sees his position as not only a job but also as a way to encourage the future generation of female scientists. He described how few female professors there were in his classes and the lack of female representation in conferences he has attended. “I feel like we need to do more in terms of providing more opportunities for girls and women to see themselves as scientists,” Mr. Carabajal said. Lucky for him, Westridge could not agree more.

(Keira K.)

![Dr. Zanita Kelly, Director of Lower and Middle School, pictured above, and the rest of Westridge Administration were instrumental to providing Westridge faculty and staff the support they needed after the Eaton fire. "[Teachers] are part of the community," said Dr. Kelly. "Just like our families and students."](https://westridgespyglass.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dr.-kellyyy-1-e1748143600809.png)