Who am I Without Perfectionism? Learning to Stand Up to My Obsessive Thoughts

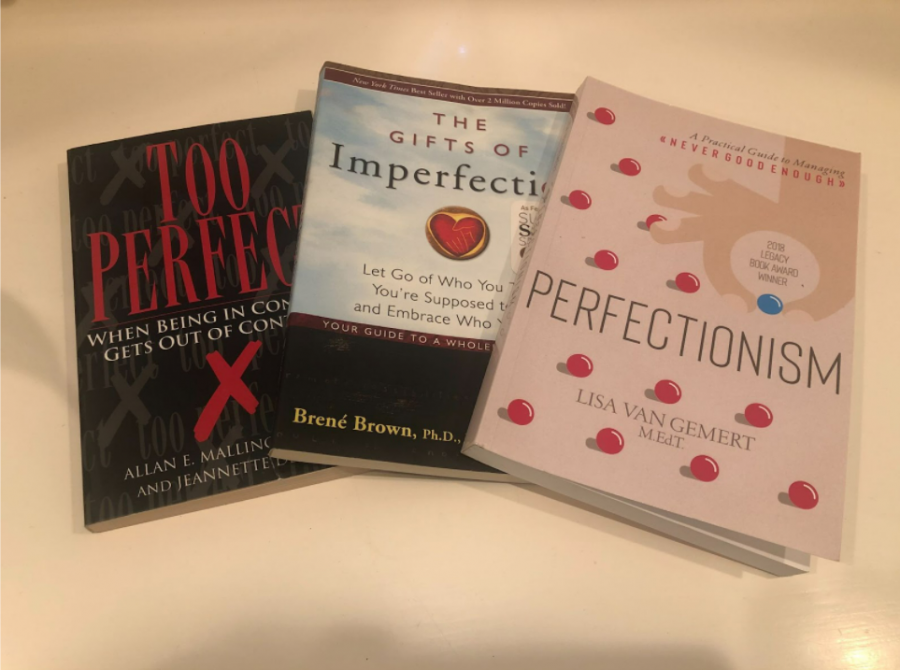

Along with attending actual therapy, my mom seemed to be ordering a new “battle your perfectionism” book each day like: Let go of Who You Think You’re Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You Are. I even got a manual of sorts, A Practical Guide to Managing ‘Never Good Enough.’

At the end of ninth grade, when I was reviewing the course catalog to choose my classes for next year, I was immediately attracted to classes denoted as honors. AP classes were even more appealing.The allure and glamour of the AP shone like a diamond necklace on display at Tiffany’s. So, although I’d been advised against it, I chose to take what’s commonly known as “the trifecta” at Westridge. I signed up for Honors Chemistry, Honors Algebra 2, and AP European History. In my mind, there was no other real option.

To be clear, nobody ever directly told me to take an AP class or the trifecta. In fact, in contrast to most of my friends and their parents, my mom and dad actually tried to convince me not to take one of the advanced courses that I desperately wanted to sign up for.

After I made this decision, I didn’t think about it again until a few weeks later when I started severely struggling with my mental health. I was forced by the people around me to realize that for the last year I hadn’t been treating my mind or my body with kindness. After this, everyday became difficult for me to get through without spending the afternoon on the couch or in my bed crying for reasons I couldn’t fully pinpoint. The unhealthy structure that I had spent the last year building to cope had finally collapsed, and with it fell my control of my emotions and my sense of self.

I soon also realized that my choice of classes was possibly yet another form of pressure and harm I had inflicted on myself. I was in a difficult situation to get out of, and both my parents and I felt that I should start attending therapy once a week.

I wasn’t fully hesitant to go to therapy because I’ve been raised by a therapist mother who always emphasized the importance of therapy, though I was extremely nervous. I had spent the last few months convincing myself that I was healthy and ok, but now I had to openly admit to a person I barely knew that I wasn’t. I’d felt that up until this point I had always been the one in my friend group to listen and help others with their problems since I had so little of my own. My friends trusted me to carry and hold their burdens with them. By admitting I was struggling to somebody, I worried I would change my relationships with the people around me.

Along with attending actual therapy, my mom seemed to be ordering a new “battle your perfectionism” book each day. White and blue Amazon-wrapped packages arrived weekly with instructional subtitles like: Let go of Who You Think You’re Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You Are. I even got a manual of sorts, A Practical Guide to Managing ‘Never Good Enough.’ I skimmed through some chapters, but it wasn’t long before I felt lost in a mess of psychological words and terms.

Therapy is where I really began to get help. It helped me recognize that the academic pressure I put on myself had begun to seep into other aspects of my life when school went online. In the beginning of quarantine, it felt as if everybody was getting A’s, either because teachers cared less or kids were cheating more. At the time, academics felt like the one thing I was “good” at, but then it became something that everyone else was “good” at too. When I could no longer receive authentic academic validation, I began to look to other places to receive it, like my personality or my body. External validation became necessary to feel good about myself.

Admitting this in therapy was both difficult and embarrassing. I didn’t want to say that the entirety of my self worth came from good grades and compliments about my body because I thought it made me sound shallow and self-absorbed. Any time the topic came up, my face would warm, and my eyes would dart around the room searching for anywhere except the computer screen where my therapist sat waiting for a response. It took a long time to be able to talk about external validation without me nervously laughing through it as if it was something that didn’t deserve to be talked about.

In therapy I also began taking a look back at the origin of my perfectionism. After all, my parents don’t outwardly care at all about my grades, and I went to a progressive elementary school that believed learning about friendship was more important than learning the times tables.

The first time I can truly remember needing to be the best was during a sixth grade project called the reading rainbow. It was a competition to see who in my 18-person class could read the most books that school year. The book count was displayed on the wall right when you entered the classroom, and every eight books you read, you got a gold star next to your name. I read 100 books and not short books either. Sure, I enjoyed reading, but if I was being honest, I did it because I wanted to win. I wanted to have 12 gold stars next to my name.

Another situation I remember is my seventh grade art class. On weekends after finishing all my academic homework in an hour or two, I would spend hours hunched over my kitchen table sobbing about my art homework because I couldn’t get it right, and I knew it wouldn’t be graded the way I wanted. I spent hours inside of the actual classroom crying as well because the black paint I had been asked to mix was always too blue or too brown, never the right shade.

Even after looking back on these experiences, I still don’t fully know why I’m wired this way. I think part of it’s a byproduct of the competitive culture at Westridge and society at large, but I can’t even fully argue that, knowing that I’ve felt this way before coming to Westridge. It could also just be a need to prove myself. I remember feeling somewhat angry that as a child my parents didn’t force me to become a star ballerina or a chess prodigy.

My need for perfection doesn’t just manifest itself academically. I can now identify more subtle ways it presents itself. For example, I absolutely hate quitting a book or a TV show once I’ve already started.

In therapy we talk about how to combat this obsessiveness. One solution is to do things that are just for me and free from external praise. For example, I could write something and not publish it in Spyglass. Or I could do work that ultimately isn’t “productive” like needle point or crocheting. That way, parts of my identity and my sense of personal worth are restored through internal praise rather than external.

Doing this has forced me to examine my values as a person. Even without the perfectionistic energy I was giving to academics, I still want to be somebody I’m proud of. Being a compassionate friend is important to me. Playing games with my family is important to me. Fashion is important to me.

Old habits die hard, but I’m making progress. This feels somewhat embarrassing to share, but I recently failed the multiple choice section of a test. I’ve never done that poorly on something in my life, yet for the first time ever I was able to accept it without letting it destroy my self-esteem. I wanted to do what I had in the past: question my identity and what the teacher must be thinking of me; instead, I came home, told my parents about it, and moved on. I spent the night cutting out pictures from magazines and collaging.

I am nowhere near where I want to be, but I have taken the first step of recognizing my need for perfection as a form of abuse to myself. I’ve promised myself to start standing up to abusive and obsessive thoughts. I’ve chosen to do this because I’ve recognized that I’ve been putting myself up to a standard I would never put someone else to, and I’ve also realized in the last few months, that basing my identity off my core values rather than my external accolades will ultimately make me happier. Whether it’s by reading 100 pages of a book and then quitting because I don’t like it, or tolerating a grade I wasn’t hoping for, I’m going to try and do better.

Eliza is a senior and the Editor in Chief of Spyglass this year. This is her fifth year on staff and her third year as an editor. Outside of Spyglass,...

![Dr. Zanita Kelly, Director of Lower and Middle School, pictured above, and the rest of Westridge Administration were instrumental to providing Westridge faculty and staff the support they needed after the Eaton fire. "[Teachers] are part of the community," said Dr. Kelly. "Just like our families and students."](https://westridgespyglass.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dr.-kellyyy-1-e1748143600809.png)