In my five years at Westridge, I have completed my fair share of required reading and heard countless complaints about “school ruining a good book.” While I agree that literature is inherently subjective—and that not everyone will enjoy every assigned book—that does not mean we should write off a piece of literature just because we have to read it.

When reading is assigned, it understandably becomes a chore, something we are obligated to complete by a set deadline. When we are required to do something, we are less inclined to enjoy it. I am by no means immune to the frustration of reading long, tedious books and the seemingly endless assignments they bring, but I have come to appreciate required reading, and I think you should, too.

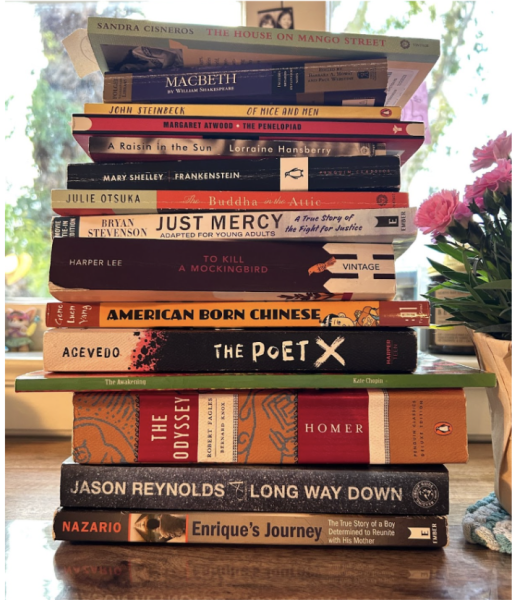

One of the more frustrating books I have read for school was Homer’s The Odyssey in ninth grade English I. Saying I loved the whole book and the experience of reading it would be an utter lie. However, there are many compelling things I took away from the 580-page epic that exceeded the story itself.

When everyone in your grade is reading the same thing, the book becomes a topic of conversation and functions as an easy way to connect with your peers. Like many others, I was inclined to share my strong feelings about The Odyssey, both in and out of class. These discussions helped me see the book in new ways and appreciate how parts of the book that either felt dull, confusing, or foreign to me resonated with others.

The slog of reading The Odyssey united my class like never before. The “trauma bond” I shared with my A block English classmates kept me motivated, amused, and helped me connect with new people.

The Odyssey also introduced other books we read for class that year, all of which added to its original text, such as The Human Comedy by William Saroyan and Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad. The Penelopiad is a narrative that precedes and exceeds The Odyssey from the perspective of Odysseus’ wife, Penelope. Margaret Atwood’s interpretation looks at the story through a modern feminist lens, delving into the ignored perspective of women and how female characters are demeaned and objectified. Penelope’s story is such a complex and beautiful one that would not carry the same weight without reading The Odyssey beforehand.

The Penelopiad serves as a valuable example of the influence literature has on other literature and the importance of critiquing written work, no matter how significant or acclaimed. Reading The Penelopiad with The Odyssey as context taught me how to articulate my frustrations in a balanced and rational way, through innovative storytelling and evidence from The Odyssey itself. Margaret Atwood’s ability to balance holding The Odyssey to a modern social standard while recognizing the norms of the time it was written is an inspiring view we can apply to all dated works.

Another one of the main joys of required reading is that you end up reading books you would never have picked up yourself. That was certainly true with Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, another book I would not have chosen to read on my own; the premise, while interesting, did not initially seem entirely unique or complex.

I was quickly proven wrong, as the 1899 novel resonated with me in a surprisingly visceral way. The protagonist, Edna, is trapped by a loveless marriage, motherhood, and societal expectations; almost every aspect of her life conflicts with her dreams of independence, art, and self-discovery.

We were tasked with reading The Awakening at a pivotally important time in our lives. In high school, we are all beginning to differentiate ourselves by discovering what we truly care about and forming our own opinions and values. The Awakening serves as an empowering reminder of the autonomy we have over our own lives and a warning of the consequences of letting societal norms and pressures dictate our future.

Like The Awakening, many of the books we read for school coincide with important phases in our lives; this is part of the reason it is valuable to read and discuss books in a group of people living through similar experiences. The opportunity to discuss with a group of people harboring similar or varying perspectives leads to discussions that enhance the reading experience and the collective understanding of each other and the book.

Often, it can feel that the only way to truly enjoy and understand a book is to relate to it in some way, whether it’s the main conflict, character, or setting of the piece; we inherently want to feel tied to the story. It is challenging to find these ties when you don’t resonate with or like the book. In situations like these, I find it important to identify an element of the book you find compelling for any reason, positive or negative. I often look for a repeated theme or image throughout the story, likely one that doesn’t fully make sense to me or seemingly relate to the story. You can then track this theme and how it adapts throughout the course of the book. I find that this helps me to connect with the work and makes my annotations more meaningful and interesting.

If you truly hate a book, my other strategy is to channel this disdain as you read and annotate. This hatred can fuel your class discussions; I really try to think about and articulate why and what I dislike—a lifeline when I was reading The Odyssey.

I understand that required reading can feel like an impossible task with all the chaos of everyday life, but I hope this impassioned rant convinced you to pick up the book you’ve been meaning to read, or finish the assigned chapters that you know are due tomorrow.

![Dr. Zanita Kelly, Director of Lower and Middle School, pictured above, and the rest of Westridge Administration were instrumental to providing Westridge faculty and staff the support they needed after the Eaton fire. "[Teachers] are part of the community," said Dr. Kelly. "Just like our families and students."](https://westridgespyglass.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/dr.-kellyyy-1-e1748143600809.png)