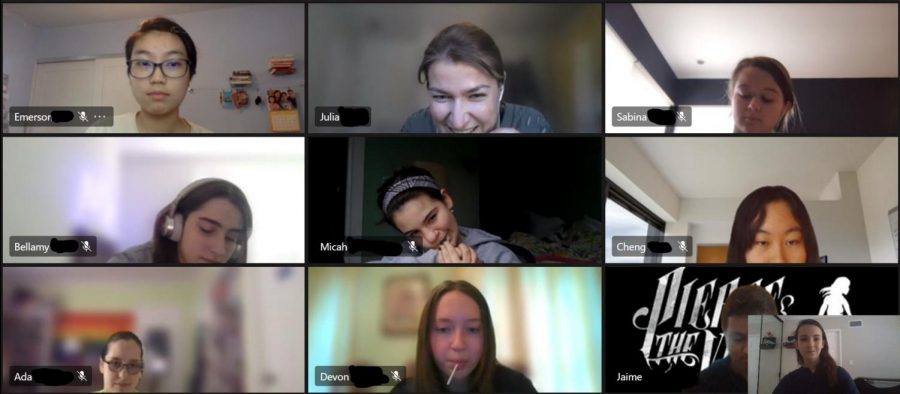

Westridge students gather for a Tiger Week class. Even when used recreationally, videoconferencing is often still mentally draining.

The Ups and Downs of Zoom Culture

March of 2020’s global lockdowns forced the world through a sudden and drastic online learning curve. Following the closures of schools, businesses, and restaurants worldwide, the world hurried to fill the void of human interaction with its virtual equivalent—videoconferencing networks like Zoom, Microsoft Teams, and Skype. While many of these platforms have existed for decades, few people were familiar with them pre-pandemic—and even fewer used them on a daily basis that has become the new normal. With its pros, cons, and 150 millisecond time lag, the adaptation to Zoom life is shaping an entirely new culture of human interaction.

The transition to online life came with some seemingly obvious guidelines: turn off your microphone and video before using the bathroom; wear pants; close your Amazon shopping spree before sharing your screen for that PowerPoint. Yet, a whole year later, horror stories of Zooms-gone-wrong continue to pile up. Between intruding parents, attacking cats, and errant children (my personal favorite incident: “Mommy! Mommy! Why is there so much poop on the floor?!”), the world simply cannot seem to get a grip on video chat protocol.

Clearly, Zoom etiquette is complicated. And it’s not black and white, either—even reputable publications can’t agree on the rules. Between The Guardian, trade magazine Digiday, and Vulture alone, you can find three differing opinions on something so seemingly simple as drinking water during calls.

Westridge students, too, have firm notions of proper video conferencing behavior.

“Don’t leave your mic on while others are talking, keep your camera on because it’s nice to see people, and don’t talk over other people,” said Nica K. ’21. Tzedek S.G. ’24 echoed a similar sentiment, adding a reminder to keep one’s camera off when calling in from a phone, and to avoid using slurs in the chat “or think, cause it’s virtual, it’s cute to say mean things.”

Lucy J. ’22 offered some advice. “Frame yourself well because nobody wants to see just a forehead; react to what people are saying, even though you might look like a bobblehead; and arrive to meetings a little bit early to greet your teacher.”

Unmuting is, undoubtedly, the number-one no-no of Zooming. “When people accidentally unmute, I panic for them and privately message them to tell them that they are very much unmuted,” Mia N. ’24 said.

Tzedek S.G. related. “There is this one really embarrassing song that’s just a ton of weird noises that was stuck in my head; I was on a call with all upperclassmen and a teacher I didn’t know. I thought I was on mute so I started singing it, then I realized after like 10 seconds of singing, that I was not. I wanted to disappear.”

While some continue to wallow in the confusing world of video conferencing etiquette, others are adapting to find joy and humanity in Zoom’s raw, often humorous portrayal of life. “The haste with which we have had to adjust to the new reality… makes it inevitable that Zoom, like life itself, will be chaotic,” Naomi Fry said in her April 2020 New Yorker article “Embracing the Chaotic Side of Zoom”. There’s something very humanizing about Zoom’s brutal honesty—whether it’s seeing a teacher’s messy room or a celebrity in pajamas, finding connection and relation in the silly, chaotic side of virtual life offers a small bit of the togetherness of which there’s been so little in the past year.

But even that just doesn’t quite cut it. Puppies marching across the screen and screaming babies in the background aside, there’s still something getting lost in translation.

Much of the complexity stems from the strange, physiological consequence of virtual interaction, the screen-induced lethargy we refer to as “Zoom Fatigue.” Humans are hard-wired for in-person connection, wrote Dr. Brenda K. Wiederhold in Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. So much of who we are and how we process the world relates directly to our physical interactions, and its virtual substitute doesn’t render flawlessly.

“Sometimes [Zoom fatigue] makes me feel super drowsy and I have headaches,” sixth-grader Shania W. recounted. “I feel it not only when I’m on calls but after. I feel tired a lot, and it makes me unable to focus sometimes when I’m doing homework. It interferes with my ability to comprehend what my teacher is saying. I feel like most of the time I’m very light-headed.”

The bottom line is, Zoom is hard. Zoom is exhausting. The amplified awkwardness of staring through cyberspace, the lack of non-verbal cues, and, consequently, the added emphasis on language—not to mention logistical and technical malfunctions—overload our brains with information and stressors irrelevant in the past. When that mental wear and tear is multiplied by eight hours a day, five days a week, or longer, and when personal interactions require just as much brainpower as professional ones, it takes a significant toll on our energy. And adapting to Zoom fatigue isn’t so easy—even a year into the pandemic.

Dr. Thea Alvarado, a professor of sociology at Pasadena City College, elaborated on the concept of collective effervescence. “It’s being in a physical location with a group of people with a common action and a common goal, and it produces a common feeling… it’s that sort of bubbly energy that you get from being surrounded by people who might be strangers, but who have this link in common, and that’s something that talking to a computer screen with faces on it for eight hours a day [cannot provide].”

Essentially, the reason we struggle to adapt to Zoom is that it simply isn’t the same as an in-person connection. While Zoom can show us the faces we’re missing, it can’t give us the feeling that we’d get by actually being with them. And as many virtual dinners and playdates and get-togethers as we host, Zoom’s illusion of togetherness simply cannot fulfill the ingrained biological need for social interaction.

Despite the difficulties of virtual communication, Dr. Alvarado sees merits in the emerging culture of online life. “I don’t think that slowing down is necessarily a bad thing,” she said, reflecting on her three children’s hectic pre-COVID schedules. “Every day was after school Mandarin classes and gymnastics, and swimming lessons and baseball and soccer. And now, being confined to home, it’s mind-boggling to think of how many activities we used to fill our time before.”

Alvarado imagines a generations-long social culture shaped by the pandemic and the unique opportunity it’s creating—that of face-to-face connection over a distance. With gestures, tone, and body language—the lifeblood of conversation—lost in translation through written communication, Alvarado favors Zoom over email and texts and hopes to see videoconferencing take a greater role in post-pandemic life. “Thankfully, with Zooming, it’s a little bit better because you can still see each other’s faces and each other’s facial expressions.”

Westridge students, however, are more interested in returning to pre-pandemic life than adapting to the new normal. “I like the convenience of video calls, but I very much dislike the outcome [and] consequence,” said Shania W. “If people are not comfortable with going back to school physically, we should still use video calls as an option, but if no one feels that way then I think we shouldn’t need to unless it is absolutely necessary.”

Mia N. agreed. “I don’t think it’s good for school because most kids in our society have very short attention spans, with, like, the rise of social media and whatnot. So I think we should continue [to use Zoom as a communication tool], just not for kids in schools.”

Someday—with any luck—we’ll return to something resembling normality and connect in-person, sans-masks, again. In the meantime, Alvarado says, we need to acknowledge quarantine’s challenges and create the space for ourselves to take a break, combat anxiety, and solidify the divide between work and fun in an online environment. And remember, by all means necessary, to stay on mute.